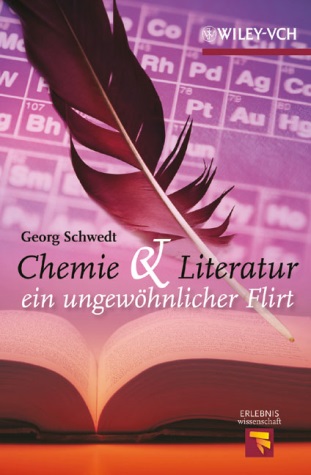

Georg Schwedt, Professor Emeritus for Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry at the Technical University of Clausthal, Germany, is author not only of many original papers but also of numerous textbooks, as well as books with historical chemistry themes and on general food chemistry, such as experiments with products from the supermarket.

For ChemViews Magazine he spoke with Dr. Reinhold Weber and Dr. Vera Koester about the thrill of using simple experiments to easily and clearly describe chemistry and how this helps us to understand our world.

You have been writing for 40 years, and in that time you’ve published 86 books. What do you enjoy about writing?

For me, what’s most enjoyable is to completely get to grips with a subject, and to select and organize content. In particular, the combination of experiments and writing has always been rewarding: Ever since I began my studies, I’ve been very much in favor of the combination of reading, manual skills, and experimental work in the lab.

How did you come up with the topics you mention in your books?

My scientific field was applied analytical chemistry. Most analytical questions and problems result more or less from daily experience: What happens? How can I analyze it? Which substances are of interest? The key again is the interaction between an experiment and the verification of a hypothesis.

In your book Dynamic Chemistry you write about sulfites in wine. The label “contains sulfites” on wine bottles was a subject of consumer concern and received criticism from winemakers and food scientists. Can you comment on the relevance of the sulfurization of wine from the viewpoints of both health and flavor?

Yes, sure. To begin with, the idea that there are no chemicals in wine – as some consumers would like to believe – is nonsense. Wine requires very interesting chemistry. I have no idea how people can live as if chemistry were something they can reject.

To come back to sulfites: Sulfites have been used for centuries. We know today that sulfites are useful in the necessary amount. Firstly, because things that would otherwise be unpleasant are suppressed, such as specific bacterial growth. Secondly, oxygen, which would alter the aroma, is intercepted by the sulfites. The motto is: As much as necessary, as little as possible. And this is technically possible today. Low sulfite contents, in a dose adapted to the wine, are absolutely necessary.

The concentration of the sulfites has to be varied according to the concentration of the substances that adsorb the sulfite, such as aldehydes, and therefore prevent them from being active. There also has to be a reserve, which is active when, for example, a lot of oxygen is present, to prevent its negative influence. This is a dynamic process. When opening a bottle of wine with the normal amount of sulfites, which is also adapted to the wine, these processes occur. This is considerably more difficult without sulfites and would lead to a different wine being produced with a different flavor.

In a Trockenbeerenauslese (a medium- to full-body dessert wine), for example, you have to sulfurize more strongly due to the content of rotten grapes.

Precisely. That is why I said that the art is to adapt the sulfite concentration to the winemaking, the type of wine. Today, every winemaker largely has this under control. The scientific basis of this is simply something we know.

You developed experiments and laboratories such as the SuperLab and the ScoLab at the central market in Hamburg (Großmarkt Hamburg) and the German Additive Museum (Deutsches Zusatzstoffmuseum). What inspired you to do so?

One reason was to help people to make sense of the additive lists of products. This way people can decide whether more than just the necessary substances are present. For example, if three preservatives are included, you can decide not to use that product. But you have to be clear about what the mode of operation of the preservative is. Another example: If I have several thickeners in a product, I know that I am being sold water. These are simple things that can be shown by experiments.

I can, for example, take a thickener, some powder, then add water and shake it. And it remains thick and doesn’t become a fluid. And then you know, oh, right, five times as much water is bound when the product is this dense. That’s a part of education. I do not have to know what the molecular chain of the thickener looks like and which side chain is where. I always say, I have to look this up in my books.

I also develop equations and formulas at a simple level, for example, in an experiment with bottled water. If you heat sparkling water, you shift the equilibrium. This can be monitored with a pH indicator. As CO2 boils off, hydrogen carbonate stays in the water, which is no longer acidic, and turns the liquid neutral. If you decompose this to carbonate, the solution becomes alkaline …

You can see this wonderfully. And you should be able to develop the corresponding equations, not memorize them.

It is important to take away the fear that science is incomprehensible and incredibly complex.

Where at the Großmarkt in Hamburg do you do your experiments?

In the building formerly called the EDEKA Fruchtkontor (fruit office). If you take the train to Hamburg you see the curving halls of the wholesale market (Großmarkt). One building stood out from the others because it was just a normal building. You could read in quite large letters “EDEKA Fruchtkontor”. They moved out and the building now houses the Additive Museum and our ScoLab.

At the student laboratory called ScoLab, a chemist, Dr. Kerstin Filipzik, offers my courses. Topics focus on fruits and vegetables: for example, the acids of various types of fruit, sugars, and natural dyes such as carotenoids and anthocyanins.

Then there is another lab in the Additive Museum. There are only a few experiments there, but both labs cooperate with each other. They have events together. There is, for example, a guided tour through the museum and afterwards selected experiments are performed in the student lab.

Is the ScoLab exclusively for students?

It is not only for students. We also have teacher training, and sometimes professionals such as chefs come for classes. Then certain spices are investigated in the experiments. We always adapt the experiments to the guests. The chemist in the lab has all my books and looks to see whether there is a suitable experiment described in there. And then a new course is created.

And this has been received very well. Do you also offer courses for the general public?

Yes, regularly. Currently, we have an event planned in conjunction with the Hamburger Großmarkt. We will have a class and then go into the Speicherstadt (Hamburg’s historic warehouse quarter), go to the Spice Museum, and go into the Speicherstadtmuseum where coffee, cocoa, and rubber are topics. And finally we will eat there. The whole course is offered as an event for connoisseurs for 60 or 80 euros. We want to involve the Speicherstadt, which I find very fascinating.

This year, on March 24, we celebrate 500 years of the beer purity law. On March 21, I am doing another course called “Chemistry for Connoisseurs”. There will be twelve experiments with beer. One is that I prepare a glass with fat and another one that is clean. Then I pour beer in both glasses. Where the fat edge is, the foam immediately collapses. Other experiments include determining which water was used for brewing. Calcium can be detected with a little bit of oxalic acid.

For those more interested in wine, I offer a similar course on wine, for example, at a vineyard in the cellar of a winery. Tannins can be detected beautifully by using iron complexes. You know the effect when you have a very strong note of the tannins on the tongue. I dilute a few drops of the red wine and add an iron salt. A color change to black or bluish shows the presence of tannin wonderfully.

It has long been debated whether white wine contains antioxidants. Red wine is much better in this regard. I take three bottles of cheap white wine, fill a shot glass half full with it, and add sodium carbonate. The fastest discoloration shows the wine with the highest antioxidant content. These are the plant phenols that are oxidized. This also correlates with scientific results. Qualitatively I get the same result as a proper wine analysis. We have tested this with a colleague in Braunschweig.

So, if you like all of the wines, then you can say to your doctor that you drink the wine with the highest amount of antioxidants.

What is your motivation for these very creative and descriptive lectures?

I enjoy these lectures greatly and this is the motivation for me to continue.

The highest praise is when somebody from the audience comes to me afterwards and says that if he/she had had chemistry classes like that he/she would have learned so much. I also find this a bit sad that chemistry classes lack this. It greatly affects our society.

Besides your work at university, you came up with these lectures and experiments and became a well-known book author. How did you manage to do all this?

I think it is bad if someone sees him-/herself at the university as merely a researcher. I have always understood myself to be a scientist at a university, a teacher, and a researcher. This also includes the raising of funds. In this capacity I published not only textbooks, I have about 240 original publications, but also popular scientific articles and books. This trinity is what should constitute a university professor. The perfect balance of this is always a personal question.

The worst thing I have heard from someone is: How nice would the university be without students? Such a person is better suited to a Max Planck or Fraunhofer Institute but not a university.

Do your colleagues share your opinion of this balance?

After having completed my habilitation, I was invited to give a lecture in Vienna, Austria, as an honor. During that time I had written a textbook called Chromatographische Trennmethoden (Chromatographic Separation Methods) and also a history of chromatography (Geschichte der Chromatographie) with the publisher Umschau.

A colleague in Vienna said to me: “Dear colleague, you should only write something like this when you are retired. Otherwise you will hurt your career.” – “I do not know whether I will still be alive then,” I replied. It has not harmed my career. And when I look my portfolio today, as I said, I have published 240 original papers and nearly 700 others, so I am very happy I did this.

Of course, your research must have a high priority; otherwise you are just a good teacher and should go to a university of applied science.

How did you manage your time?

That is an important question, as you have to keep things ticking over. You cannot worry about all the small things; there is no time for that. I tried to organize myself and the workflow of the group as efficiently as possible and give responsibilities to co-workers to minimize unnecessary meetings. For example, I always asked the people in the administration to tell me exactly how they needed things to be done. I then did it that way. However, I also told them not to come to me afterwards and request things be done in another way. Don’t throw a spanner in the works.

Working in industry was not for me. I have been on the verge several times, with concrete offers, but have always declined. The money has not excited me. Freedom is worth much more. To my colleagues today I say: “Do not moan, make use your freedom.” Despite the limitations we have today, the freedom that still remains should constitute the joy of the profession. The beauty is also that you can always remain among the young people as a professor at university.

Do you have time for other interests?

Yes, I regularly make trips to the river Ahr, go hiking in vineyards, and travel a lot. Every month my wife and I go somewhere: for example, in the Thuringian Forest, to go hiking, visit museums, dine out – this is relaxation for me.

My wife and I both get up early. I use the time after breakfast until noon to work. Then I read the newspaper, and in the afternoon I have spare time. I am a pensioner then.

Thank you very much for the interesting interview.

Georg Schwedt, born in 1943, studied chemistry in Goettingen, Germany, and received his PhD from the University of Hanover, Germany. After that, he took the position of department head at the Regional Analytical Authority in Hagen, Germany, and habilitated in Analytical Chemistry at the University of Siegen, Germany, in 1978. Upon receiving a professorship for analytical chemistry in Goettingen, he was appointed director of the Institute of Food Chemistry and Analytical Chemistry at the University of Stuttgart.

Since 1987, he has been a professor of inorganic and analytical chemistry at the Technical University of Clausthal, Germany. Since his retirement in 2006, he has been working at the University of Bonn, Germany.

Selected Awards

- GDCh (German Chemical Society) prize for journalists and authors (2010)

Selected Articles/Books

|

Dynamische Chemie, Georg Schwedt, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2015. ISBN-10: 3527339116 |

|

Analytische Chemie: Grundlagen, Methoden und Praxis, 3., überarbeitete und aktualisierte Auflage Georg Schwedt, Torsten C. Schmidt, Oliver J. Schmitz, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2016. ISBN-10: 3527340823 |

|

Experimente rund ums Kochen, Braten, Backen, 3., aktualisierte und erweitere Auflage Georg Schwedt Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2015. ISBN-10: 3527339671 |

|

Zuckersüße Chemie: Kohlenhydrate & Co., 2. Auflage Georg Schwedt, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2014. ISBN-10: 3527338683 |

|

Chemie und Literatur – ein ungewöhnlicher Flirt, Georg Schwedt, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2009. ISBN-10: 352732481X |

|

Experimente mit Supermarktprodukten: Eine chemische Warenkunde, 3., erweiterte und aktualisierte Auflage, Georg Schwedt, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2008. ISBN-10: 3-527-32450-X |

|

Taschenatlas der Analytik, 3., überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage, Georg Schwedt, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2007. ISBN-10: 3-527-31729-5 |