One big challenge for the production of synthetic cells is that they must be able to divide. Kerstin Göpfrich, Heidelberg University and Max Planck Institute for Medical Research, Heidelberg, Germany, and colleagues have introduced a reproducible division mechanism for synthetic vesicles. It is based on osmosis and can be controlled by an enzymatic reaction or light.

Building and Dividing Cells

Organisms cannot simply emerge from inanimate material (“abiogenesis”), cells always come from pre-existing cells. The prospect of synthetic cells newly built from the ground up is shifting this paradigm. However, one obstacle on this path is the question of controlled division—a requirement for having “progeny”.

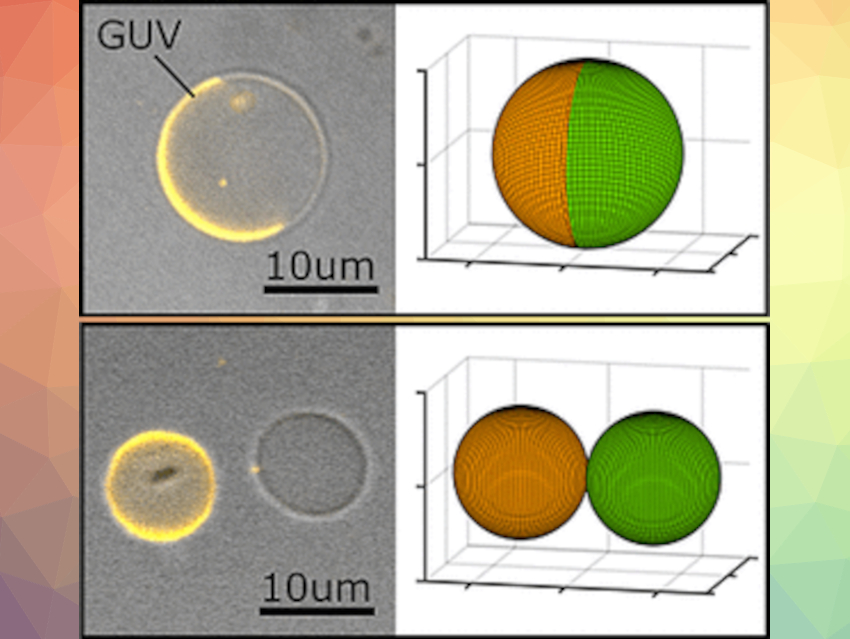

The researchers have reached a milestone by achieving complete control over the division of vesicles. To achieve this, they produced “gigantic unilamellar vesicles”, which are micrometer-sized bubbles with a shell made of a lipid bilayer that resembles a natural membrane. A variety of lipids were combined to produce phase-separated vesicles—vesicles with membrane hemispheres that have different compositions.

When the concentration of dissolved substances in the surrounding solution is increased, osmosis causes water to exit the vesicle through the membrane. This shrinks the volume of the vesicle while keeping the membrane surface equal. The resulting tension at the phase interface deforms the vesicles. They constrict themselves along their “equator”—increasingly with increasing osmotic pressure—until the two halves separate completely to form two (now single-phase) “daughter cells” with different membrane compositions. When the separation that occurs depends only on the concentration ratio of osmotically active particles (osmolarity) and is independent of the size of the vesicle.

Controlling the Process

The method by which the osmolarity is raised plays no role. The methods used by the team included using a sucrose solution and adding an enzyme that splits glucose and fructose to slowly increase the concentration. Using light to initiate the splitting of molecules in the solution gave the researchers complete spatial and temporal control over the separation. Using tightly controlled, local irradiation allowed the concentration to be increased selectively around a single vesicle, triggering it to selectively divide.

The team is also able to grow the single-phase cells back into phase-separated vesicles by fusing them with tiny vesicles that have another type of membrane. This was made possible by attaching single strands of DNA to both types of membrane. These bind to each other and bring the membranes of the daughter cell and the mini vesicle into very close contact so that they can fuse. The resulting gigantic vesicles can subsequently undergo further division cycles.

“Although these synthetic division mechanisms differ significantly from those of living cells,” says Göpfrich, “the question arises of whether similar mechanisms played a role in the beginnings of life on earth or are involved in the formation of intracellular vesicles.”

- Division and Regrowth of Phase‐Separated Giant Unilamellar Vesicles,

Yannik Dreher, Kevin Jahnke, Elizaveta Bobkova, Joachim P. Spatz, Kerstin Göpfrich,

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021.

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202014174