Christmas is perhaps the most sensorially rich period of the year. The festive atmosphere is shaped by a complex mosaic of scents, colors, sounds, and textures that together create what we often call “magic.” Yet behind this magic lies an impressive variety of chemical phenomena. Every smell linked to our childhood memories, every sparkle of tinsel, every flavor in Christmas sweets, and every shine on decorated surfaces originates from a specific chemical mechanism. Chemistry not only explains these phenomena but makes them possible in the first place, enabling the production of materials, pigments, foods, and technologies we now take for granted.

The purpose of this article is to highlight the hidden chemical world of Christmas. From spices to the LEDs that illuminate our trees, from the composition of ornaments to the crystalline wonders of snow, chemistry reveals that Christmas is not only a cultural celebration but also a physicochemical event.

Aromas and Flavors: Organic Compounds That Define the Season

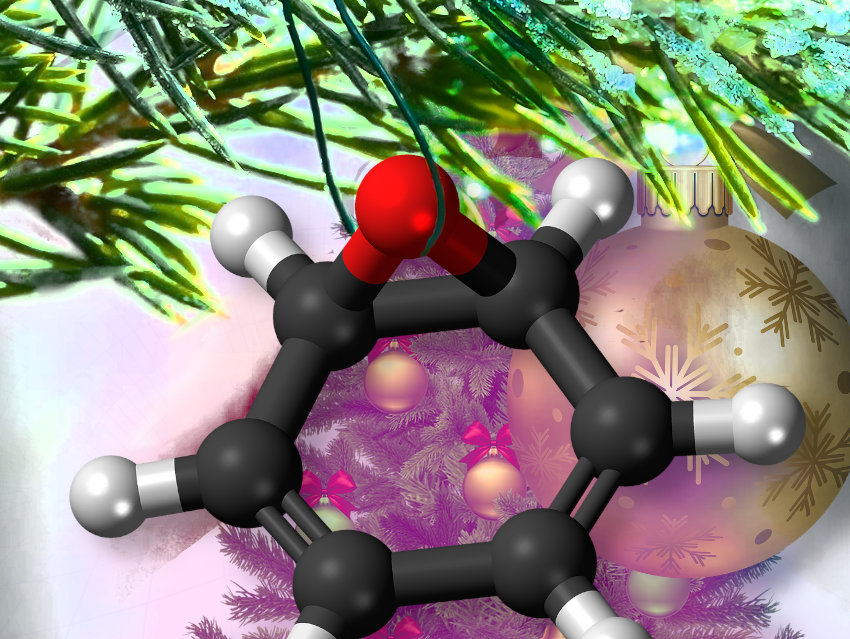

The olfactory experience of Christmas is arguably its strongest sensory signature. The spices that dominate seasonal baking, like cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, and vanilla, are rich sources of volatile organic compounds. Each has a unique chemical structure responsible for its characteristic aroma.

Spices

Cinnamon owes its fragrance to cinnamaldehyde, an aromatic aldehyde with conjugated double bonds that evaporates easily and strongly activates olfactory receptors.

Clove contains eugenol, a phenolic compound with a sweet–spicy profile and notable antimicrobial properties, which explains its traditional use beyond cooking.

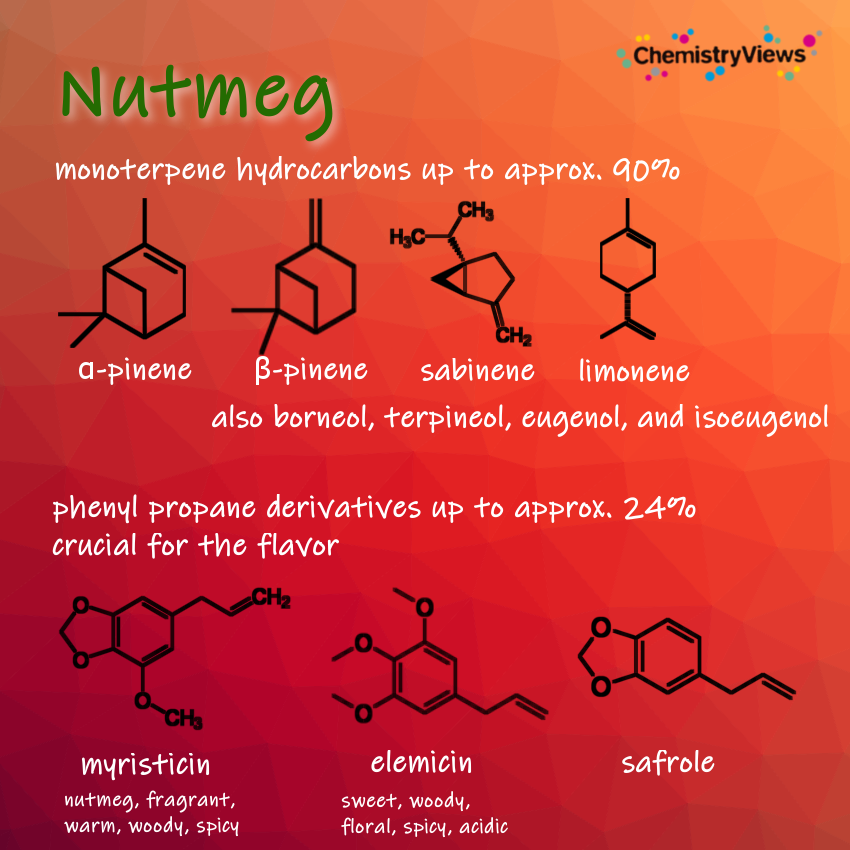

Nutmeg contains myristicin and safrole, phenylpropene derivatives that contribute to its warm, slightly mysterious aroma.

Vanilla, on the other hand, is one of the world’s most recognizable flavoring agents thanks to vanillin, a phenolic aldehyde with a pleasant, sweet aromatic profile. Although natural vanillin is extracted from the pods of the orchid Vanilla planifolia, global demand is now met mostly by synthetic production, either through lignin oxidation or, more recently, through guaiacol transformations.

.png)

Even citrus fruits, long associated with the holiday season, are characterized by terpene compounds such as limonene. The burst of aroma released when squeezing the peel of an orange or mandarin comes from the rupture of microscopic oil glands that spray limonene into the air.

Millard Reaction

But the flavor and aroma of Christmas foods are not due solely to volatiles from spices. The Maillard reaction plays an equally crucial role, transforming color, flavor, and aroma during cooking. This non-enzymatic interaction between sugars and free amino acids produces a vast range of aromatics, including pyrazines, furans, ketones, and aldehydes that give roasted or caramelized surfaces their characteristic taste.

The beloved Greek melomakarono, for example, owes much of its complexity to the interplay between the Maillard reaction and the natural caramelization of honey sugars.

The Light of Christmas: Exploring Semiconductor Physics and Chemistry

Lighting is another key element of the festive atmosphere. The shift from incandescent and fluorescent bulbs to LEDs (light-emitting diodes) has been a true revolution, both energetically and aesthetically. LED technology relies on semiconductor physics, and when an electron recombines with a “hole” in the semiconductor material, it releases energy as a photon.

The color of this emitted light depends on the band gap of the material. For this reason, while older technologies provided only a limited color range, modern LEDs can produce almost any hue.

The color of this emitted light depends on the band gap of the material. For this reason, while older technologies provided only a limited color range, modern LEDs can produce almost any hue.

The most common materials for Christmas LED lights are gallium-based compounds such as gallium nitride (GaN) and aluminium gallium indium phosphide (AlGaInP). Each combination provides a different band gap and thus a different color. The development of blue GaN LEDs was critical for creating white LEDs and ultimately for mainstream LED lighting.

Unlike incandescent bulbs, LEDs waste very little energy as heat and convert most of it into visible light. They have a longer lifespan and a far lower risk of overheating, making them ideal for decorating natural trees, paper, or fabrics.

The Christmas Tree: The Biochemistry of Chlorophyll and Terpen

The fir or pine tree that decorates most homes during the holidays is a remarkable example of biochemical resilience. Conifers retain their green color even in the coldest months thanks to the structure and stability of chlorophyll. Chlorophyll a and b, the main forms found in conifers, contain a porphyrin ring with a central magnesium ion. This molecular design allows them to absorb red and blue light while reflecting the green we see.

The longevity of conifer needles also results from their morphology. They have a low surface-area-to-volume ratio and are covered with a thick waxy cuticle that reduces water loss and protects against cold. Their resins, rich in terpenes, act as a natural chemical shield against pathogens and physical damage.

The aroma of a natural Christmas tree, one of the most iconic scents of the season, is due to terpenes such as α-pinene, β-pinene, and limonene. These highly volatile molecules evaporate easily from needles and branches when warmed indoors, blending with the aromas of candles and baked goods to produce the unique “olfactory pulse” of Christmas.

Snow: Crystallography, Thermodynamics, and Light Scattering

Snow, a natural emblem of Christmas in northern regions, is an astonishingly complex chemical phenomenon.

A snowflake forms when atmospheric water vapor freezes around a tiny condensation nucleus, typically a particle of dust or salt. Solid water adopts a hexagonal crystal structure due to the angles formed by hydrogen bonds, giving rise to the snowflake’s six-armed symmetry. The uniqueness of each snowflake does not stem from randomness but from tiny fluctuations in temperature, humidity, supercooled vapour conditions, and airflow during formation. These factors alter the rate of crystal growth, producing an endless variety of shapes.

Snow appears white because of diffuse light scattering. Ice crystals are not inherently white; ice is semi-transparent, but snow consists of countless small crystals whose surfaces reflect and refract light in many directions. When all visible wavelengths scatter evenly, the resulting perception is white.

Candles and Combustion: The Chemistry of Heat and Aroma

Candles have been used in winter celebrations for centuries.

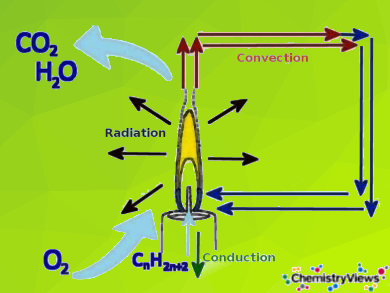

Candle wax consists primarily of paraffin, a mixture of alkanes (C₂₀–C₄₀). When the wick is heated, it melts the paraffin, which then rises by capillary action and evaporates. The gaseous paraffin combusts with oxygen to produce carbon dioxide, water vapor, and heat. The flame’s behavior depends on oxygen availability, and insufficient oxygen leads to incomplete combustion and soot formation.

Scented candles contain mixtures of essential oils released gradually during burning. These aromatic compounds must be thermally stable enough to avoid decomposition yet sufficiently volatile to diffuse into the air. This combination of warmth and fragrance enhances the perceived “cosiness” of the festive season.

The Colors of Christmas: The Chemistry of Pigments and Metals

Christmas colors have deep cultural symbolism, but their chemistry is equally fascinating.

The bright red associated with Santa Claus and traditional decorations often derives from synthetic azo dyes, which contain the characteristic –N=N– bond responsible for strong absorption in the visible spectrum.

Anthraquinone dyes form another important family known for their stability and vividness. Green ornaments and printed surfaces often owe their color to copper phthalocyanines, highly stable pigments with intense color and exceptional light and heat resistance.

Gold decorations, widely used in gift wrapping and ornaments, are produced either from thin metallic foils (e.g., aluminium or brass) or from pigments containing iron and titanium oxides that exhibit strong reflectivity.

Polymers, Materials, and Artificial Holiday Effects

Christmas ornaments are also products of chemical technology. Many are made of polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), or polyethylene polymers that allow a wide variety of shapes, colors, and mechanical properties. Traditional glass ornaments still exist but are largely replaced by lightweight plastics with advantages such as impact resistance, low cost, and suitability for mass production.

Artificial snow used in decorations is now commonly made from sodium polyacrylate, a superabsorbent polymer capable of holding hundreds of times its weight in water. When hydrated, it expands and acquires the appearance and texture of fresh snow.

Even gift packaging is a product of modern chemistry. Wrapping papers use highly stable pigments, often with polymer coatings (such as polyethylene or polypropylene) that provide strength and gloss.

How Scents and Colors Influence the Brain

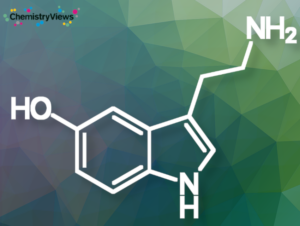

Christmas aromas influence not only smell but also emotional tone. The olfactory pathway is directly connected to the brain’s limbic system, which regulates memory and emotion. Vanillin, cinnamaldehyde, and limonene, for example, can enhance feelings of well-being through neurochemical mechanisms related to serotonin.

Warm colors such as red and gold create the illusion of increased temperature and are closely linked to feelings of comfort and safety. LED lighting also affects the circadian rhythm, boosting energy and mood during the darker days of winter.

The chemistry of Christmas is not an abstract concept but a reality we experience daily without noticing. Every scent, every light, every color, and every material of the season is the result of specific chemical mechanisms and properties. Understanding these phenomena allows us to appreciate the role of chemistry in everyday life and to recognize that the “magic” of Christmas is, in essence, the beauty of matter and energy in interaction.

Merry Christmas and Merry Chemistry!

The Author

Dr Spiros Kitsinelis

Vice-Chief Editor of Chimica Chronica and Publishing Manager since 2016; also Publishing Manager for the Journal of the Association of Greek Chemists (JAGC).

Also of Interest

Collection: Chemistry & Spices

A compilation of articles on chemistry related to spices

Collection: Chemistry & Light

A compilation of articles on chemistry related to light

Collection: Chemistry & Baking

A growing compilation of articles on chemistry related to baking

Collection: Exploring the Chemistry of Candles

🕯️🧪 A compilation of articles and videos on chemistry related to the candle and candle flame

.png)

.png)