In 2019, the annual global production of the semimetal tellurium was 670 tons [1]. Compared to the world’s annual production of 3,300 tons of the significantly rarer element gold this is rather low. Worth mentioning: Au only occurs in the 77th position in the earth’s shell compared to tellurium, Te, which is in the 73rd position. Three quarters of tellurium production goes into steel refinement, the rest is mainly used in semiconductor technology, such as the production of Peltier elements (for cooling and heating purposes), rectifiers, and infrared and X-ray detectors. Moreover, potassium tellurite has been used in microbiology since the 1930s when Alexander Fleming reported its antibacterial properties [2].

1 A Strange Semimetal

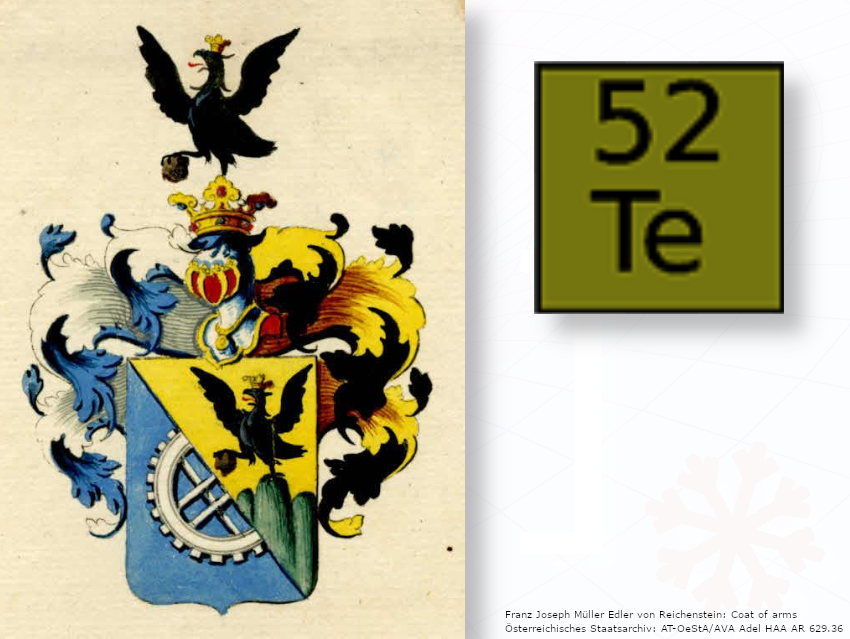

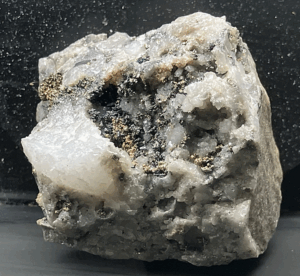

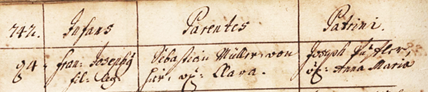

The first person to notice the brittle silver-grey semimetal was the Austrian mining officer Franz Joseph Müller. This year marks the bicentenary of his death on October 12th, 1825. In 1781, in his function as “Thesauriatsrat” of the Transylvanian gold mines, Müller began to investigate strange Transylvanian ores. Near Nagyág (now Săcărâmb in Romania), he noticed a gold ore that always yielded less gold than expected. Even more puzzling, however, was a silver-grey ore from the Mariahilf mine near Zalathna (now Zlatna, Romania) (see Fig. 1).

In August 1782, Anton Ruprecht, professor of chemistry in Schemnitz (today Baňská Štiavnica, Slovakia), to whom Müller had sent ore samples, thought that it was antimony. Müller had initially thought it was bismuth but soon corrected himself. Between 1783 and 1785, the results of Müller’s investigations were published in five reports [3], the first being dated “Hermannstadt, den 21. Sept. 1782”. His final conclusion was [4]: “Our mineral is not mineralized, but in the reguline state, and a solid semimetal … Our semimetal is not antimony … is also not bismuth … But what kind of semimetal is our mineral? … Is this problematic mineral perhaps a new, hitherto unknown semimetal?”

The Swedish chemist Tobern Olof Bergman was supposed to verify Müller’s assumption that the ore from the Mariahilf mine was a previously unknown semimetal. However, Bergman’s unexpected death on July 8th, 1784, prevented this question from being clarified.

Several years passed before Pál Kitaibel, later professor of botany and chemistry at the university of Pest, became interested in Transylvanian ore. In an unpublished “Beytrag zur näheren Kenntnis des so genannten wasserbleyigen Silbers (Argent molybdique) von Deutsch-Pilsen” [Contribution to the Further Knowledge of the So-Called Water-Lead Silver (Argent molybdique) from Deutsch-Pilsen], Kitaibel described the properties of the element that would later be named tellurium. The Austrian mineralogist Franz Joseph Anton Estner informed the chemist Heinrich Martin Klaproth of this discovery [5]. Klaproth isolated the semimetal, which Müller called “metallum problematicum”, from ore samples still originating from Müller. On January 25th, 1798, Klaproth gave a lecture at the Academy of Sciences in Berlin [6], acknowledging Müller’s achievements, but—because Müller had not given this metal a name—himself naming it the “new peculiar metal tellurium, borrowed from the old Mother Earth”.

Figure. 1. Specimen of native tellurium on quartz from Zlatna (today Faţa Băii),

Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Austria. (© photo: R. W. Soukup)

2 What Do We Know About Franz Joseph Müller?

The history of the discovery of tellurium is already convoluted. Additionally, it must be noted that many biographies of its discoverer contain serious errors. It begins with an incorrect entry about Müller in Constantin Wurzbach’s Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich (in 1868) [7] and is still relevant today. To give one example, the portrait that was printed on an Austrian stamp to mark the 250th anniversary of Müller’s birth is not that of Franz Joseph Müller von Reichenstein, but of his son Johann [8].

2.1 Early Years—Education and Marriage

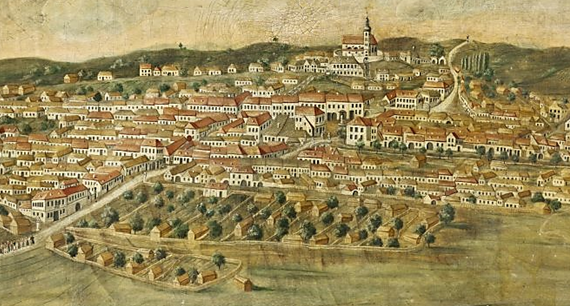

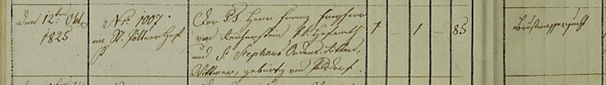

There is also confusion about his place and date of birth. Here are the facts: as we know from the baptismal register of Poysdorf in Lower Austria, Franz Joseph Müller was baptized on October 4th, 1742, in the parish church of Poysdorf (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Excerpt of the Baptismal Register of Poysdorf 1733–1784 for October 4 (1)742.

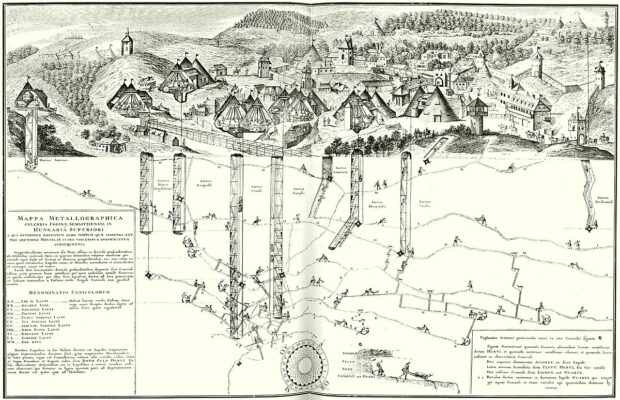

Franz Joseph Müller was the son of the judge Sebastian Müller (who died in 1768) and his wife Clara (née Lettner). Sebastian Müller was active in Poysdorf (see Fig. 3) in the service of the Counts Veit Eusebius and Johann Wilhelm of Trautson [9], who resided in nearby Poysdorf Castle in Poysbrunn. In 1756 we find “Müller Franc.” as “Aust. Boystorffensis Poet” in the 8th volume of the register of the University of Vienna, whereby an ‘n’ was subsequently inserted above the line for the surname and the ‘y’ was corrected from ‘l’ for the place of birth [10].

Figure 3. Poysdorf 1822. (Source: Stadtgemeinde Poysdorf, Vino Versum)

The next report about the young student is dated August 23rd, 1763: Müllner (sic), who submits certificates of his mathematical knowledge, asks for permission to “practice his skills” as a voluntary trainee in the mining town of Schemnitz (today Banská Štiavnica, see Fig. 4). During his first year there, Müller became acquainted with mining practice. From September 18th, 1764, Müller attended the lectures of Professor Nicolaus Joseph Jacquin, the first holder of the newly established chair for chemistry, metallurgy, and docimastics at the Upper Hungarian mining school [11].

Figure 4. Mine map of Schemnitz (today Banská Štiavnica) by the Italian natural scientist and soldier Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli printed in Den Haag 1741.

In 1765, Müller married Margaretha He(c)hengarten (1744–1786), the daughter of Court Chamber Councillor Count Bartholomäus He(c)hengarten (1702–1773). In the summer of the same year, Müller received “permission for a pilgrimage” [12] from Empress Maria Theresia (1717–1780), the ruler of the Habsburg monarchy. This trip to the Marian pilgrimage site of Maria Schoßberg (Šaštín, Slovakia)—a location not so far from Poysdorf—was probably Müller’s wedding trip.

On September 9th, 1766, the Court Chamber in Vienna agreed to Müller’s being employed as a paid trainee by the “Oberstkammergrafenamt” in Schemnitz. Müller subsequently accompanied his father-in-law on his visits to mines in Inner Austria. On August 1st, 1768, he was entrusted with the function of a mine surveyor at the Windschacht in Schemnitz.

2.2 Multiple Mining Posts in Austria and Hungaria

In the autumn of 1770, Müller was transferred to Oravița in the Banat, a region in south-eastern Europe in an area that today belongs to the states of Romania, Serbia, and Hungary, as Mining Directorate Assessor. On April 2nd, 1775, Oberbergmeister Müller was informed that Empress Maria Theresia had appointed him to the position of a Vice Factor and First Director in Schwaz in Tyrol [13].

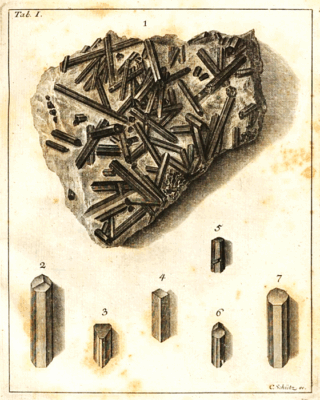

Just three months later, Müller inspected the high-altitude Schneeberg state silver mine in the Ridnaun Valley in South Tyrol, Italy. During this period, Müller was also scientifically active alongside his administrative work. On the occasion of a business trip to a gold mine near Zell am Ziller, Müller travelled further into the back of the valley to the “Zemmgrund”. Not far from a gorge, he discovered beautiful stem-like crystals of black tourmaline. Müller reported the discovery of the tourmalines and their pyroelectric properties in an essay he sent to the well-known natural scientist Ignaz von Born, who printed this report in 1778 (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Joseph Müller’s Message on the Tourmalines or “Ash Pullers” Discovered in Tyrol, addressed to Ignaz Edler von Born, Krausische Bookshop, Vienna, 1778, Plate I.

In January 1777, Müller was required to take a four-week vacation to deal with his inheritance from his father in Poysdorf: „Berichtigung seiner zu Poysdorf in Unterösterreich noch zu fordern habenden väterlichen Erbschaft“ [14].

On September 18, 1778, the directorate in Schwaz was informed that Vice Factor Müller had been appointed “k.k. Siebenbürgischer Münz- und Thesauriatsrat” [Imperial-Royal Transylvanian Council of the Mint and Treasury]. Without delay, Müller travelled to his new place of employment in Hermannstadt (now Sibiu in Romania). There, he began inspecting smelting works and hammer mills near Hațeg, near Zalathna (Zlatna), and Szertesc (Certeju de Sus) in 1779. He visited the gold and silver mines of Nagyág (Săcărâmb), Verespatak (Roșia Montană), Faczebaj (Faczebaia, Faţa Băii), and the copper mines of Diemrich (Deva) [15].

In Transylvania, Müller became a very active collector of minerals and ores. He sent rare ore specimens not only to the Imperial Natural History Cabinet in Vienna, but also to the Royal Mineral Cabinet in Paris, France.

In February 1787, he took over the management of the mining and salt inspectorate in Zalathna [16]. On January 1st, 1788, Müller was appointed Gubernatorial Councillor and on July 24th, 1788 he was ennobled in recognition of his merits [17]. On April 12th, 1802, Franz Joseph Müller, now “Edler von Reichenstein”, took up a position as court councillor in Vienna.

2.3 Mineral Collection and Descendants

In his Viennese apartment at St. Pöltnerhof, Krugerstraße Nr. 1007 (today no. 5; the house standing here today was built in 1897) [18], he set up a mineral collection, which was open to the public. On October 15th, 1818, he retired after 54 years of service [19]. On December 7th, 1820, he was raised to the rank of baron. “Herr Franz Freyherr von Reichenstein, K.k. Hofrath und St. Stephans Ordensträger, Witwer, gebürtig von Polsdorf [sic], Katholisch” died—as we know from the death register of the parish church St. Augustin in Vienna—on October 12th, 1825 from dropsy of the breast (see Fig. 6) [20].

Figure 6. Excerpt of the Death Register 1815–1829, p. 92, St. Augustin in Vienna.

Baron Müller von Reichenstein left three children: Johann Müller von Reichenstein became Assessor at the Zalathna Mining Court and from 1807 he was Gubernatorial Secretary of Mining in Styria and Carinthia [21]. Anna, born in 1773, married the Transylvanian Thesauriatsrat and administrator of the Zalathna estate, Matthias von Kimerle. Karl Emerich Müller von Reichenstein, born in 1780, was Royal Hungarian Truchsess (steward) and Councillor of Mines (Bergrat) in Transylvania. Franz Joseph’s grandson Franz Freiherr Müller von Reichenstein (1819–1880) became Vice-Chancellor of the Transylvanian Court Chancellery in Vienna in 1861. He was a member of the House of Representatives from 1863 to1865.

3 Mullérine

Several mineral species discovered in the Carpathian area were first described by Müller von Reichenstein, among them alabandite, a manganese blende MnS, discovered in Săcărâmb (1784) or sylvanite, discovered 1785 in Baia de Arieş [22]. In honor of Franz Joseph Müller von Reichenstein, the French mineralogist François Sulpice Beudant suggested in 1832 that the white tellurium AuTe₂ occurring in Transylvania should be called “Mullérine” [23]. In 1877, the name was changed to “Krennerite”.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Klara Soukup cordially for proofreading.

References

[1] Tellur, Wikipedia (last access May 6th, 2025)

[2] Alexander Fleming, On the specific antibacterial properties of penicillin and potassium tellurite, J. Pathol. Bacteria 1932, 35, 831-842. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1700350603

[3] Simone Huber, Peter Huber, Franz Joseph Müller Freiherr von Reichenstein – Seine Bedeutung für die Mineralogie und seine Veröffentlichungen, res montanarum 1992, 5, 21.

[4] Franz Joseph Müller, Fortsetzung der Versuche mit dem aus der Grube Maria Hilf in dem Gebirge Faczebay bey Zalathna in Siebenbürgen vorkommendem vermeintlichem gediegenen Spießglanzkönige, Physikalische Arbeiten der einträchtigen Freunde in Wien, aufgesammelt von Ignaz Edlen von Born 1785, 1/3, 47 ff.

[5] Ekkehard Diemann, Achim Müller, Horia Barbu, Die spannende Entdeckungsgeschichte des Tellurs (1782–1798), Chem. Unserer Zeit 2002, 36, 334-337. https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-3781(200210)36:5<334::AID-CIUZ334>3.0.CO;2-1

[6] Waldauf von Waldenstein, Über den eigentlichen Entdecker der Tellurerzes, Erneuerte vaterländische Blätter für österreichischen Kaiserstaat 79, 3. Oktober 1818, p. 315 f.

[6a] Anika Ullmann, Problematicum und Plagiat: Wer entdeckte Tellur?, Rohstoff.net 2021. (accessed July 25, 2025)

[7] István Tringli, Franz Joseph Müller als bekannter und unbekannter Wissenschafter, res montanarum 1992, 5, 16. (Both the name and professional title of Müller’s father are incorrect here)

[8] Rudolf Werner Soukup, Letter to the Editor: Anmerkungen zur Entdeckungsgeschichte des Tellurs von E. Diemann, A. Müller und H. Barbu [5]), Chem. Unserer Zeit 2002, 36, 413.

[9] Josef Preyer, Franz Joseph Müllner – Vorfahren und Kindheit, res montanarum 1992, 5, 23-25.

[10] Kurt Mühlberger, Register (matriculation book) of the University of Vienna, Austria,1746/47-1777/78 with university records, chronicles and enrollments, Vienna, Austria, 2014, p. 429.

[11] Josef Vozár, Franz Joseph Müller in der Slowakei, res montanarum 1992, 5, 37.

[12] Slovenský banský archív v Banskej Štiavnici, fond Hlavny komornogrófsky úrad, Resolution 16. Juli 1765.

[13] Georg Mutschlechner, Franz Joseph Müller in Tirol, res montanarum 1992, 5, 26.

[14] Tiroler Landesarchiv, Innsbruck, Geschäft von Hof 1777 (vol. 1518), f. 24´.

[15] Ion Dordea, Aus dem Leben und Wirken des Gubernialrats Franz Joseph Müller von Reichenstein als Leiter des Siebenbürgischen Münz- und Bergwerksthesauriats in den Jahren 1778 – 1803, res montanarum 1992, 5, 32.

[16] Staatsarchiv Klausenburg, Siebenbürgisches Montan-Thesauriat 1787, Z. 640, p. 1-3.

[17] Österreichisches Staatsarchiv: AT-OeStA/AVA Adel HAA AR 629.36 Müller, Franz Joseph, siebenbürgischer Thesauriatsrat, Adelsstand, „Edler von Reichenstein“, 1788.07.24.

[18] Anton Ziegler, Adressen-Buch, Wien, Austria 1823, p. 157.

[19] Wiener Zeitung 258, 10. November 1818, p. 1029.

[20] Aside from the misspelling “Polsdorf” for Poysdorf, which can occasionally be observed in former centuries, the entry in the death register contains an incorrect age specification, namely: “Age 85 years”. Franz Joseph Müller von Reichenstein had begun his 84th year a few days before the day of his death.

[21] Ion Dorea, Aus dem Leben und Wirken des Gubernialrats Franz Joseph Müller von Reichenstein als Leiter des Siebenbürgischen Münz-und Bergwerksthesauriats in en Jahren 1778-1802, footnote 5, res montanarum 1992.

[22] Ossi Horovitz, Müller von Reichenstein an the Tellurium, Noesis 2008, 33, 113-118.

[23] F. S. Beudant, Traité élémentaire de Minéralogie, 2.ed., Vol. 2, Paris, France, 1832, p. 541.

Also of Interest

Collection: Significant Milestones in Chemistry: A Timeline of Influential Chemists

Starting from the early alchemists we take a journey through time to examine how each of these chemists pushed the boundaries of what is possible