Enrico Fermi (1901–1954) received the 1938 Nobel Prize in Physics “for his demonstrations of the existence of new radioactive elements produced by neutron irradiation, and for his related discovery of nuclear reactions brought about by slow neutrons”. He made significant contributions to statistical mechanics, quantum theory, and nuclear and particle physics.

Fermi in Rome—Childhood

Enrico Fermi was born in Rome, Italy, on September 29, 1901, to Alberto Fermi, a railway employee, and Ida De Gattis, an elementary school teacher [1,2].

Despite not having obtained advanced academic qualifications, Alberto, originally from Piacenza, managed to secure respectable employment positions thanks to his dedication to work, inspired by the family role models he had grown up with. He was made a railway administrator, a role that brought him to Rome, where he met Ida. Together they had three children: Maria, Giulio, and Enrico, the youngest. Enrico spent the first two and a half years of his life in the countryside, raised by a wet nurse, before returning to his family home at 19 Via Gaeta.

Not many details are known about this residence, except that the building is located near Rome’s central railway station—a convenient location for Alberto Fermi’s work. Today, a commemorative plaque can be found at the entrance of the building (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The plaque at Via Gaeta 19, Rome, reads: ‘The most illustrious Italian physicist of the 20th century, Enrico Fermi, was born in this house on September 29, 1901. His fellow citizens remember him with admiration.

Today, the building consists of several privately owned apartments, some of which are used as bed and breakfasts—owing to the central location of the area—or as temporary accommodation for individuals who need to relocate for health-related reasons.

Enrico did not live in this building for long: in 1908, the Fermi family moved to one of the residences constructed at the beginning of the last century to accommodate the large influx of public officials to Rome, the newly established capital of Italy. The new home was located at 133 Via Principe Umberto, still very close to Termini Station.

It was certainly a modest dwelling. In her biography of Fermi, his wife, Laura, mentions that one of the difficulties the family had to face was the cold. “For all its pretense of elegance—two statues were in the hall at the feet of two ample stairways—the building at Via Principe Umberto 133 had provided none of the niceties of modem living. There was no heating of any kind, and the three Fermi children, Maria, Giulio, and Enrico, often had chilblains in the winter” [Atoms in the Family, p. 13].

During this period, Enrico spent most of his time with his siblings, particularly with Giulio: the two were very close and enjoyed a wide range of activities, one of their favorites being the construction of model airplane engines.

However, Enrico was forced to confront the pain of losing a family member at a very young age. In 1916, Giulio passed away due to an untreated illness, leaving a profound void in the family. At that point, Enrico—perhaps as a way to cope with the traumatic event—began to devote himself even more intensely to his studies. He would spend his afternoons in one of Rome’s best-known squares, Piazza Campo de’ Fiori, where one of the city’s largest markets took place daily.

The young Enrico would carefully save his early earnings to invest in a wide range of books on mathematics, physics, and geometry, sharing this passion with a schoolmate, Enrico Persico, who would also go on to become a notable Italian physicist. Recognizing the boy’s remarkable enthusiasm, Adolfo Amidei, a friend of his father, advised him to apply to the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy, a prestigious institution renowned for its teaching in these fields.

Fermi in Pisa—Student Years

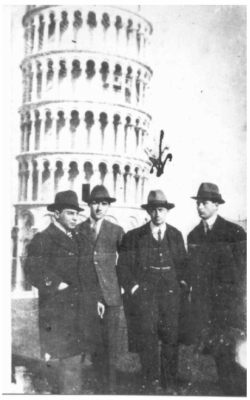

Fermi’s university years were smooth and passed without significant difficulties. It was during this time that he formed a close friendship with Franco Rasetti, his fellow student and future colleague (see Fig. 2).

When speaking of Fermi’s residences, one must also mention Rasetti’s childhood home, which was located near Pisa. It is said that while living in the university dormitory far from his own home, Fermi would often visit the Rasetti family.

Their friendship was strengthened by many shared interests: both had a love for nature and long mountain hikes, and above all, they enjoyed playing pranks on other students. They even created a mock “Anti-Social Society” dedicated to this pastime. While these years were personally enriching for Fermi, the same cannot be said for his scientific training. Fermi already possessed a strong foundational knowledge, and few new topics were explored during this period; in fact, he was often the one giving lessons to his professors!

Figure 2. Enrico Fermi (second from right) with a group of physicists in front of the Tower of Pisa. [AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives].

Fermi in Rome—Teaching and Success

After graduating in 1922, Fermi decided to continue his academic career in his native city. During those years, he had to face yet another loss: that of his mother, Ida, who had never recovered from the death of her second child. Ida never saw the Fermi family’s third home, a small villa at 12 Via Monginevra, in the Montesacro district. Though farther from the city center than their previous residences, it was located in a more modern area of Rome. The house was assigned to Alberto Fermi before its construction was fully completed. However, Enrico’s father did not live there long, as he passed away in 1927.

Meanwhile, Enrico became increasingly involved with the Physics Institute on Via Panisperna, which can be considered his true home during the period from 1926 to 1938. After two brief periods of research in Germany and the Netherlands, Fermi began working at the Royal Institute of Physics of Rome under the supervision of then-director Orso Mario Corbino.

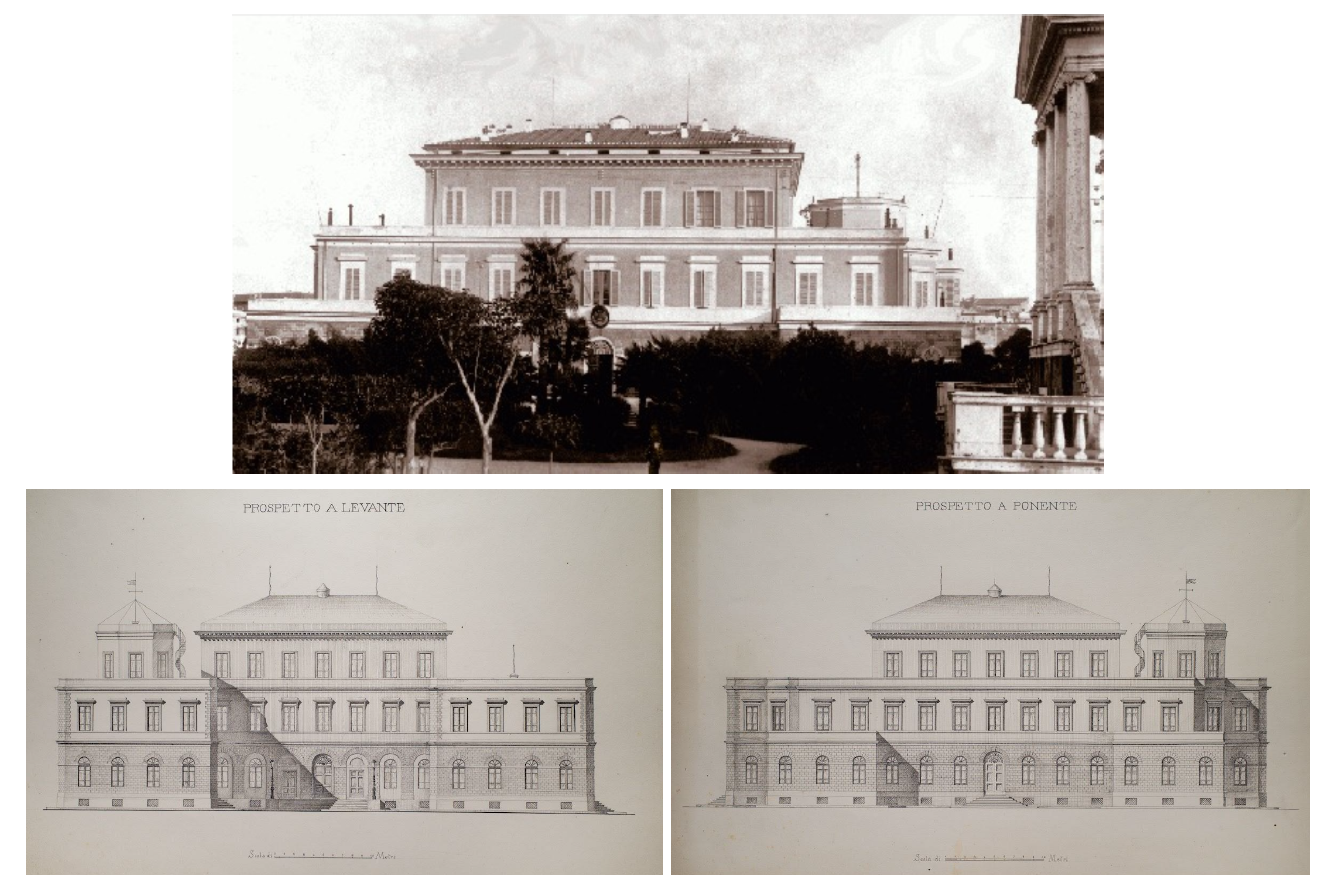

The Physics Institute on Via PanispernaLocated on the hill of Via Panisperna, the Institute was inaugurated in 1877 (see Figs. 3–5) [4] as part of a broader initiative to reorganize the scientific institutions of Rome—intended not only as the political capital but also as the scientific center of a newly unified Italy. Among its main promoters were Quintino Sella, a scientist and government minister; the chemist Stanislao Cannizzaro; and the physicist Pietro Blaserna, founder and first director of the Institute. Blaserna was the driving force behind the vision of a modern, well-equipped physics institute with a strong emphasis on laboratories and experimental physics. He also developed the practical and operational plans for its realization—a true “house of physics” to which he devoted his energy and professional expertise.

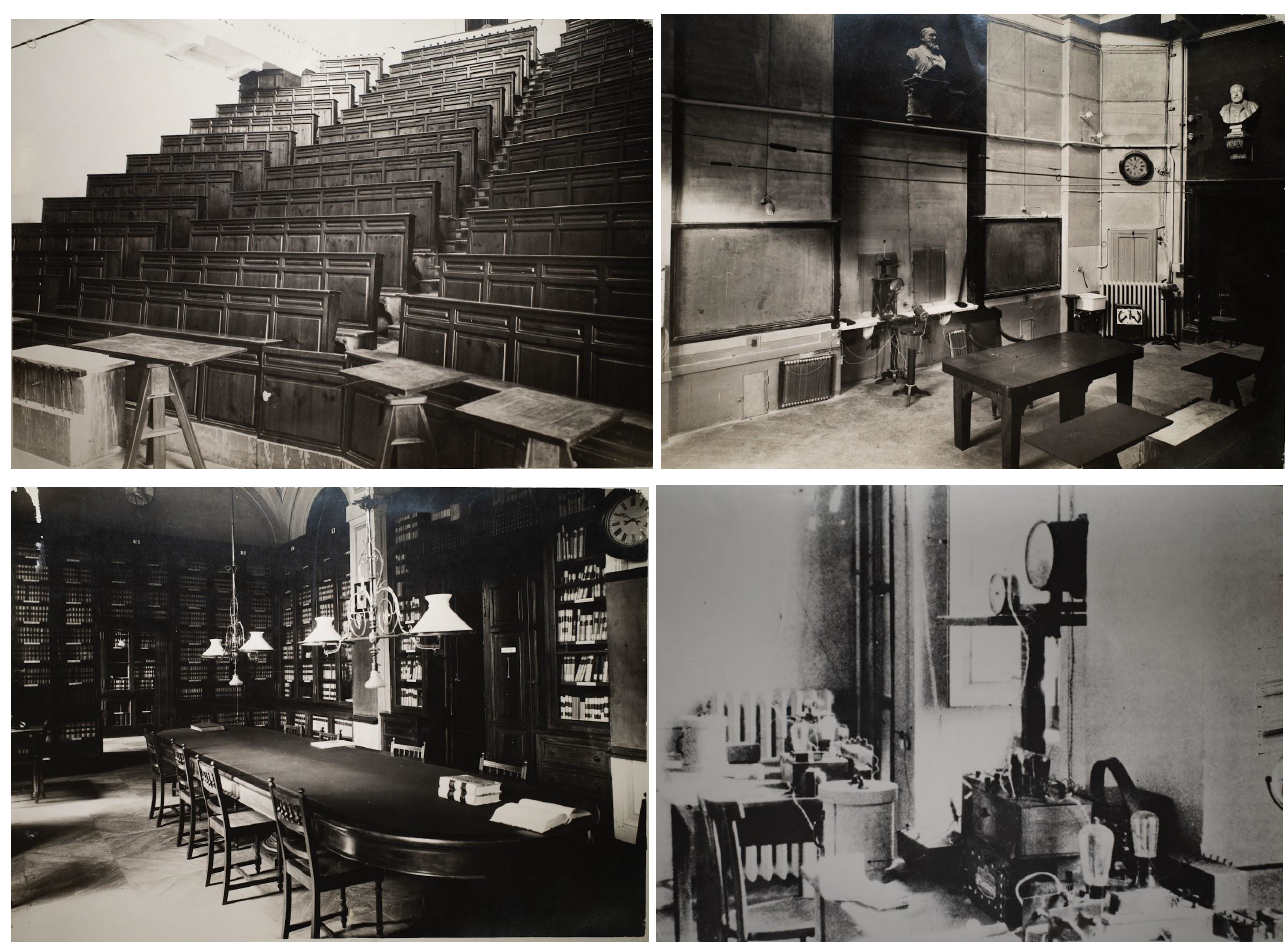

The building consisted of three floors plus a basement. On the ground floor were the classrooms (see Figs 6 and 7), the workshops where instruments were built, and several laboratories for students; on the first floor, the professors’ offices and additional laboratories (see Figs. 8 and 9); and on the top floor, the residence of the Institute’s director. The Institute of Radiology for Public Health, which played a fundamental role in Fermi’s discoveries was located in the basement.

In 1918, following the death of Blaserna, the directorship of the Institute was entrusted to Orso Mario Corbino [5]. Under his leadership, the Roman school of physics and the Royal Institute of Via Panisperna became central to an extraordinary era for Italian science, gaining international recognition through pioneering research in the newly emerging field of nuclear physics. In 1937, the Faculty of Physics was relocated to the newly constructed university campus, which still houses Sapienza University and serves as the main site for physics students today. The historic institute on Via Panisperna assumed various roles, gradually losing its scientific function and becoming part of the Ministry of the Interior’s complex. With Law No. 62 of March 15, 1999, the building was officially recognized as a historic site and was converted into a research center. In 2019, after twenty years of meticulous restoration, the Historical Museum of Physics and the Enrico Fermi Research and Study Center was inaugurated within the building (see Fig. 10). Today, the facility has a dual mission: on one hand, to preserve and widely disseminate the historical and scientific legacy of Enrico Fermi, with a particular focus on younger generations; on the other, to pursue cutting-edge research across various sectors of physics through an interdisciplinary approach.

|

Fermi became the first person to teach theoretical physics in Italy, beginning his lectures at the Via Panisperna institute in 1926. This location soon emerged as a prominent center of scientific research, largely due to the work of Fermi and his colleagues, establishing it as a vital hub for scientists of the time. The significance of the institute is exemplified by the high-profile participation in the first International Conference on Nuclear Physics, held at Via Panisperna in 1931.

On that occasion, Fermi succeeded in bringing together many of the most distinguished scientists of his era. Among them were honorary president Guglielmo Marconi, guest of honor Marie Curie, and renowned physicists such as Niels Bohr, Robert Millikan, and several future Nobel laureates. One of the most iconic images from the event captures the attendees on the staircase of the institute’s inner courtyard (see Fig. 11).

Figure 11. The First International Congress on Nuclear Physics in 1931. [Archive of the Department of Physics of the “Sapienza Università di Roma”]

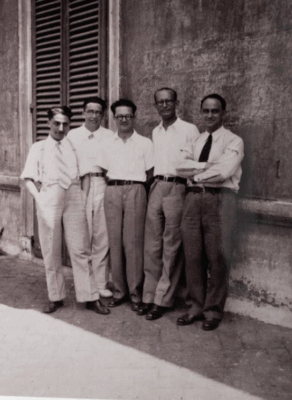

One of Fermi’s undeniable strengths was his ability to surround himself with outstanding researchers. Around him formed the renowned group known as the “Via Panisperna Boys,” which included Rasetti—who had come to Rome as Corbino’s assistant—Edoardo Amaldi, Emilio Segrè, Oscar D’Agostino, and Bruno Pontecorvo. The famous photograph depicting the group (see Fig. 12) was taken by Bruno Pontecorvo himself on the terrace located on the first floor of the building.

Figure 12. The Via Panisperna Boys photographed at the Royal Physics Institute in 1934. [Archive of the Department of Physics of the “Sapienza Università di Roma”]

These young men—initially Fermi’s students and later his colleagues and friends—were responsible for one of the most sensational discoveries of that era: the discovery of radioactivity induced by slow neutrons. This breakthrough demonstrated that it was possible to render certain elements radioactive by bombarding them with appropriately slowed neutrons.

It is said that Fermi was inspired by the water in the famous “goldfish fountain” (see Fig. 13), located at the center of the building’s inner courtyard. Indeed, his intuition proved correct: it is the collisions with protons—found in the nuclei of hydrogen atoms—that slow down the neutrons. As is well known, water is a substance rich in hydrogen. In 2012, this fountain was declared the first Italian Historic Site by the European Physical Society.

Figure 13. The goldfish fountain in the inner courtyard of the Institute. [Archive of the Department of Physics of the “Sapienza Università di Roma”]

One aspect of this experience that we wish to highlight—beyond the clear historical significance of the discovery—is the way in which it has often been described as “physics done with string and sealing wax.” This expression underscores how the great determination of these physicists led to remarkable results, even with limited resources (see Figs. 14–16).

For example, many of the instruments used, such as the Geiger-Müller counter (see Fig. 14), were built by the physicists themselves in Via Panisperna. They consisted of a hermetically sealed copper tube with a metal wire stretched along its axis between two insulating plugs, connected to a telephone counter that registered the passage of electrons. The materials were all sourced by the scientists, who had to contend with limited financial resources. It is said that many of the elements used as targets came from the collection of a monk passionate about chemistry. For practical reasons, these samples were mostly cylindrical to facilitate exposure to neutron sources and counters (see Fig. 15). Furthermore, due to the close proximity between the experimenters and the radioactive sources, the young scientists used lead wells (see Fig. 16) to protect themselves from gamma radiation. These had two removable lids with a handle.

Figures 14 to 16. Example of some of the instruments used by Enrico Fermi’s group at the Royal Institute of Physics.

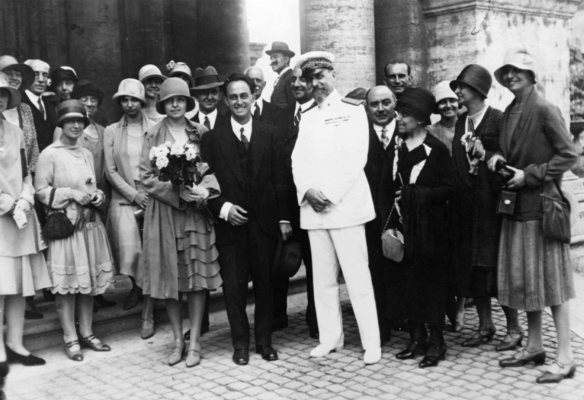

On July 19, 1928, Enrico married Laura Capon, a young student of natural sciences from a well-established upper-middle-class Roman family of Jewish origin (see Fig. 17).

Figure 17. The marriage of Enrico Fermi and Laura Capon in 1928. [AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.]

It was during this period that Fermi moved house once again, relocating to 28 Via Belluno (see Fig. 18), near Villa Torlonia—which would later become the private residence of Benito Mussolini. The apartment was located on the top floor of the building and consisted of six rooms.

We can quote Laura’s words: “In Rome we had settled into a top-floor apartment in a co-operative building. The apartment was pleasant, full of light and air, and more than adequate for a couple. The ceilings in the six rooms were high, the decorations in good taste.” [Atoms in the family, p. 63]

Today, the building is located in a very busy area, at the heart of Rome’s university nightlife district, and has been converted into the headquarters of a political party.

Figure 18. Plaque, located at Via Belluno 28, reads: ‘The physicist Enrico Fermi lived in this house from 1928 to 1938’.

This was not the only apartment inhabited by the Fermi-Capon family, which had grown to four members with the birth of Nella and Giulio. Ten months before Enrico was awarded the Nobel Prize, he and Laura moved to Via Magalotti, not far from one of the most beautiful parks in Rome: Villa Borghese.

This apartment was undoubtedly the most luxurious the family had ever lived in. The home had a total of three bathrooms and several bedrooms. One of the details that most struck Laura can be directly highlighted by her own words: “This larger apartment was near Villa Borghese, the main park of Rome. We had bought it because I had been attracted by the idea of a green-marble-lined bathroom” [Atoms in the Family, p. 113].

Even today, this area of Rome is considered highly elegant—clear evidence of the significant stature Enrico had attained during that period.

However, Laura and Enrico had little time to enjoy their new, luxurious home. Following the enactment of the racial laws in 1938 and upon receiving news that Enrico had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, the Fermis decided to leave Italy. On the evening of December 6, 1938, accompanied to Termini Station by their dear friends Ginestra and Ugo Amaldi, along with Franco Rasetti, they departed for Stockholm and then, without returning to their homeland, continued on to New York, USA.

Thus began a second chapter—both scientific and personal—in the life of Enrico Fermi. What is considered the Roman period of his life ends here. Finally, we summarise the main places of Enrico Fermi’s story in a map of Rome (see Fig. 19).

Figure 19. Map of Rome with the main places of Enrico Fermi’s story.

References

[1] Laura Fermi, Atoms in the Family: My Life with Enrico Fermi, University of Chicago Press, USA, 1954.

[2] Emilio Segrè, Enrico Fermi, Physicist, University of Chicago Press, USA, 1970 3. ISBN-13: 978-0226744728

[2a] C. Bernardini, L. Bonolis (ed.), Conoscere Fermi nel centenario della nascita, Bologna, SIF, 2002.

[2b] Miriam Focaccia, Pietro Blaserna and the Birth of the Institute of Physics in Rome: A Gentleman Scientist at Via Panisperna, Springer Nature Switzerland, 2016, then 2019.

[2c] Miriam Focaccia, Orso Mario Corbino: Un manager della ricerca all’Istituto fisico di Roma, Bologna, SIF 2022.

Other useful reference texts

– Giovanni Battimelli, Maria Grazia Ianniello, Fermi e dintorni: Due secoli di fisica a Roma (1748-1960), 2012.

– Edoardo Amaldi, Giovanni Battimelli (ed.), Michelangelo De Maria (ed.), Adele la Rana (ed.), Da via Panisperna all’America: I fisici italiani e la Seconda guerra mondiale, 2022.

– Luisa Cifarelli, Giuseppe Pelosi (ed.), Il Grande Fermi, 2024.

– Gianni Battimelli, L’eredità di Fermi. Storia fotografica dal 1927 al 1959 dagli archivi di Edoardo Amaldi, 2003.

Also of Interest

- Enrico Fermi Museum, Via Panisperna 89 A, Rome, Italy

Quiz: Guess the Houses and Molecules

Discover where famous chemists lived 🏠 and who synthesized iconic molecules 🧪

Appeal: Historic Chemists and Their Houses: Please Share Your Knowledge!

Tell us about the houses of famous chemists you know—we’d love to publish more articles about historic residences