Professor Daniel Rabinovich, The University of North Carolina at Charlotte, USA, conducts research in the field of synthetic and structural inorganic, bioinorganic, and organometallic chemistry. His main focus is on the coordination chemistry of sulfur- and selenium-based ligands and the preparation of synthetic analogues of metalloenzymes. And he also collects stamps with chemistry motifs.

In this ChemistryViews interview, he talks about what fascinates him about chemistry stamps, scientific outreach and education, and what it takes to get people excited about chemistry.

Do you have a favorite stamp?

There is no lack of favorite stamps. There are stamps that have some design error …

… that was what I was wondering, if there are design or chemistry errors on some stamps.

Oh, yes. Yes, there are.

Among those, my favorite stamp is one that was supposedly honoring the plastics industry in Monaco. This industry is not really that big in Monaco. This small country – I have never been there – is known for Formula One racing, tourism, casinos, etc. Anyway, they wanted to have a stamp for the plastics industry. The stamp shows a molecule of methane that enters some kind of chemical apparatus and plastic is coming out. It is not really that plastics are not made from methane. However, the worst part is that they show the structure of methane as C4H. The H is in the center and four carbons are surrounding the hydrogen. That is not an error that makes this is a rare, expensive stamp; millions of stamps were printed like that. So that’s a nice story about that stamp.

Among those, my favorite stamp is one that was supposedly honoring the plastics industry in Monaco. This industry is not really that big in Monaco. This small country – I have never been there – is known for Formula One racing, tourism, casinos, etc. Anyway, they wanted to have a stamp for the plastics industry. The stamp shows a molecule of methane that enters some kind of chemical apparatus and plastic is coming out. It is not really that plastics are not made from methane. However, the worst part is that they show the structure of methane as C4H. The H is in the center and four carbons are surrounding the hydrogen. That is not an error that makes this is a rare, expensive stamp; millions of stamps were printed like that. So that’s a nice story about that stamp.

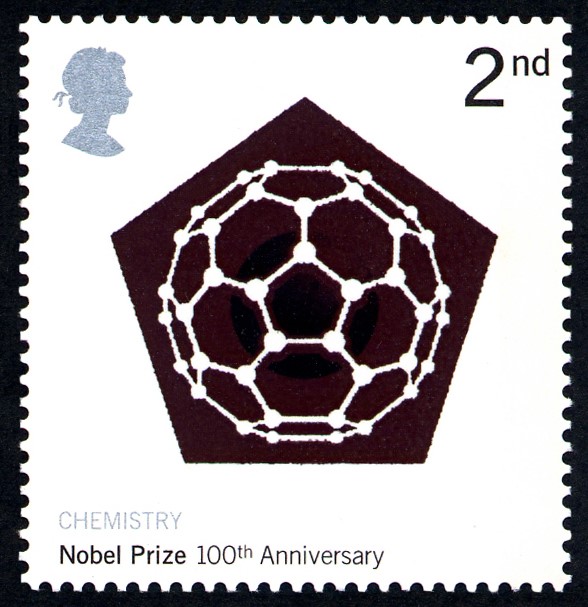

There are other stamps that are very well designed: There is a stamp from the UK. It was the centennial of the Nobel Prizes and it is a nice stamp that shows C60. That is already pretty nice for a stamp, but the stamp was also printed with thermochromic ink. So it changes color with heat. And when you touch the stamp it reveals in the center a darker sphere. That is supposed to be like a helium atom trapped inside C60, an endohedral fullerene. That is a lot of chemistry hidden in a little postage stamp.

These stories are what makes it really nice. They make it nice for a conversation piece and teaching tool.

By stories, you mean the chemistry or details of who commissioned the stamp and why?

.jpg) Mostly the chemistry; not the technical stuff. If there is a molecule, why is this molecule shown on this stamp? For example, there is a stamp from Austria that shows von Reichenstein who discovered tellurium. It is not such a common element, and at first you wonder why a stamp from Austria shows tellurium. There is also a stamp from Romania that shows the symbol of tellurium. So what is the connection of tellurium and Romania? Tellurium was the only element that was discovered in Romania. There were some Austrian mineralogists who explored the mines in Transylvania and on one occasion, they discovered tellurium.

Mostly the chemistry; not the technical stuff. If there is a molecule, why is this molecule shown on this stamp? For example, there is a stamp from Austria that shows von Reichenstein who discovered tellurium. It is not such a common element, and at first you wonder why a stamp from Austria shows tellurium. There is also a stamp from Romania that shows the symbol of tellurium. So what is the connection of tellurium and Romania? Tellurium was the only element that was discovered in Romania. There were some Austrian mineralogists who explored the mines in Transylvania and on one occasion, they discovered tellurium.

You can build all these stories and make these unexpected connections. It is great for teaching or for communicating science to a larger audience. That is how you get people interested in science. It is not about describing what is the melting point of something or properties like that. It is all about stories.

Another thing is, when I give these presentations with stamps, it is very visual. I may have 140 slides for a 45-minute presentation. When, for example, the hosts see 140 slides, they say: “Oh, my God. It is going to be like three hours.” And then it goes very, very fast because it is mostly images and short stories.

Where do you get the stamps from? How do you scan all the stamps and find the chemistry-related ones?

First, most of the stamps are not expensive. The stamp market is supply and demand and how old and how rare the stamps are. Very few of these are rare, so very few are expensive. That makes them in a way harder to find. I can go online to eBay or other online auction houses. Occasionally – before the pandemic – I went to stamp shops, but nobody is going to have chemistry-related stamps. There is not a big market for that. So I had to start looking at maybe medicine, minerals, and some more common topics. Stamp collectors either collect a country collection or a topical collection and that can be sports, butterflies, or space – but chemistry is quite rare.

So it takes time, a lot of patience, a lot of looking online. Now the internet helps me to find out what chemistry stamps are there.

It is also hard to define exactly what is chemistry. To keep things entertaining, I define chemistry very broadly for the purpose of the collection. So I would include some medicine, some physics, some biology, definitely minerals and mining, and some other collector topics like the metric system, diseases, fireworks, stained glass – there are all kind of connections to chemistry.

Are there motifs that occur very often, for example, a molecule or a Nobel Laureate?

There are hundreds of stamps with minerals. Every country that has some mining will depict some minerals because it is visually appealing and easy to show.

Some countries are, I would say, more proud of their chemical heritage and they have a longer chemistry history and thus they have more stamps related to chemistry. So that is the case of Germany, France, and Russia; that is not the case for the US. This correlates to a certain degree with the value that society attaches to chemistry.

You will be surprised that there are lots of countries you do not think about being key players in the world of chemistry and yet they do have chemistry-related stamps, for example, Afghanistan, Bahamas, Belize, Bhutan, Cape Verde, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, Fiji, Honduras, Jamaica, Laos, Malta, Mongolia, Panama, San Marino, etc. Yes, all of these have chemistry-related stamps!

Do you have gaps in your collection where you know that there is a certain stamp but you have never got it?

Yes, I know of some. For example, one of the most popular figures on postage stamps is Louis Pasteur. There are Louis Pasteur, Marie Curie, and some other scientists that are represented in many countries. So I would say there are maybe 100 or 120 different Louis Pasteur stamps from say 40 to 50 different countries. Some have a connection to France, are maybe former French colonies, a French-speaking country, but some other countries just wanted to portray a famous scientist.

There are a couple of stamps from France with Louis Pasteur that are way too expensive that I know I will never get. I mean we are talking about like 10,000 dollars. So if I had 10,000 dollars, I would do something else with the money. I would not spend it on a postage stamp. Because it is not about having a complete collection, it is not about filling the gaps. It is just about my passion for stamps and for science communication, and building a story so as to enjoy science communication.

Anyway, most of the stamps that I can afford to have, I do have. I have been doing this for a while. It is a source of pleasure, not really an investment. A hobby.

People do not write that many letters anymore, so are there fewer stamps produced? And what is the future of the stamp and the stamp collector?

That is a good question. I think sooner or later stamps will disappear just like writing checks and so many other things.

Even serious stuff such as job offers and letters of recommendation are sent by email. Stamps will disappear, but post offices will remain. So even with electronic communication people will still need to send and receive packages.

The original idea of a postage stamp, which was a receipt for mailing, for the prepayment of a letter or package, will fully disappear. As a hobby it is not going to disappear because there are just too many people who collect. It is affordable, it is interesting. I think, as a hobby, stamp collecting will remain just as there are still people who collect match boxes or vinyl records.

I went into the post office on campus the other day and during some small talk with the postal worker, we were saying “How can you today realize the age of a person?” – “Well, the younger generation, students on campus, have never licked a stamp.” Even if they occasionally have used stamps, I think most of the stamps in the US and in many other countries are now self-adhesive; they are like stickers. This is similar to the question for older people: “Have you ever used a typewriter?” “Have you ever used a rotary phone?” So the new question to ask is, “Have you ever licked a stamp?”

That’s great. You said several times that you use stamps to communicate science and that this is one of the main reasons why you collect stamps. Can you say a bit more about that?

Yes. Sometimes I write for different publications such as RefleXions, the periodical of the American Crystallographic Association, or Chemistry International, the quarterly newsmagazine of IUPAC – I have a column there. It is a fairly knowledgeable audience, but certainly chemists, like everyone else, never stop learning and my stories can contribute to that.

More broadly, it can be, for example, lectures for local sections of the American Chemical Society who again often include chemists but sometimes there are students, there are spouses, there are some people who have very little understanding of chemistry. And sometimes I talk to a lay audience. You can convey the excitement of chemistry and why the word chemistry or chemical is not a bad word, etc.

I also use stamps in my teaching. If I am teaching a general chemistry section of 180 students, there are relatively few chemistry majors. There are biology majors, engineers, etc. My goal is not to convert everybody to chemistry but to just help this large audience to have respect, to have a basic understanding of chemistry, to have some knowledge of how chemistry works. So I use stamps to, again, tell the story of the periodic table or some interesting stories that will enhance a lecture.

I use stamps wherever I can. It is fun. I am very passionate about it. And I see it as my mission to do science communication. I try to customize my talk to every specific audience. And I still mail letters and I try to use stamps there. A nice surprise these days.

How did your stamp collecting start?

I do not know exactly. I know I started collecting when I was ten. There were no stamp collectors in my family in Peru. I do not know where I got the idea, maybe from a friend or from TV but stamp collecting then was a much more common hobby. Without much guidance from my family, I did not have a nice stamp album or tweezers, nothing. So I remember that I was removing the stamps from envelopes and as I did not know where to keep the stamps, I soaked them in water and stuck them to the walls. At that time these were figures of animals or landscapes or whatever. I think my parents saw that I had an interest in stamps and then we went to the local stamp shop in Lima and I got some guidance on what kind of collections there are and how to keep the stamps in an album.

I started with chemistry stamps years later when I became a chemistry major in college. Since then it has always been a hobby, and a source of distraction and balance. Much later I started really applying that hobby to my teaching and for science communication. So this is how it evolved from a pure hobby to something that I can marry with my professional interests.

How did your interest in chemistry start?

Well, that is not very unusual: I had a good chemistry teacher in high school. She is still alive and in fact just recently I got hold of her number through the alumni association of my high school; I need to get hold of her. She was really an inspiration, a really good teacher. In Peru where I was growing up, there were no elective courses. Everyone took the same courses regardless of their interests or abilities. So back then everybody had to take two years of chemistry, two years of physics. I think it was until my sophomore year in high school, so three years before graduating, I thought I would maybe study medicine or architecture, which I kind of liked, but then I really fell in love with chemistry. In those days we could do a lot more with chemistry, maybe safety was a little bit lax. I remember we were doing mouth pipetting of hydrochloric acid and we had some fires. Nothing happened, no accidents or anything, but we would be doing experiments that we are probably not allowed to do today.

Many people who are not interested in chemistry had a bad teacher. It is not because chemistry is not appealing, or it is hard. Having good or bad teachers makes a huge difference.

And I am a strong advocate for students to do work in the lab, to do research, very early, before they already have developed maybe a misconception of chemistry. I work with many high-school students doing research in the lab trying to help them see what we like about chemistry. And by this to maybe complement the instruction that they get at their high schools. I try to do my part to show them what the beauty of chemistry is and what inspires me to be a chemist.

What do you mean when you say you work with many high-school students in the lab?

At UNC Charlotte at my institution we do not have a Ph.D. degree in chemistry. So all my work over the years – I have been at UNC Charlotte for 25 years – has been done by undergraduate students, master’s students, and high-school students.

Wow. How are you doing this?

There are challenges, of course, associated with doing research with these younger scientists because typically, especially through the academic year, they can only do research on a part-time basis. High-school students and undergraduate students are all taking classes and have other things to do. That is the challenge of finding projects where they can make a contribution but just working a few hours each week.

I tailored my projects over the years to be more accessible to students with more limited experience. My research requires the synthesis of typically I would say organic ligands, small organic molecules. They take maybe two or three steps to make – it is not too complicated. It is not a synthesis of a natural product in microscale or anything like that. But still it is before many of these young students have even taken any organic chemistry. So, things that we sometimes take for granted, they have never heard about. They are dedicated, they are smart, they are curious, and they have usually taken one or two semesters of chemistry, general chemistry in high school. So they can handle moles and thermochemistry and kinetics but they have not seen any organic chemistry. Organic chemistry is typically not covered in high-school chemistry in the US. Only in the second year of college do they take organic chemistry.

We are talking about freshman high-school students trying to do organic chemistry without having ever seen organic chemistry in the classroom. So that is a challenge but it is empowering as well because in a way it is easier to teach organic chemistry than other fields. The basic concepts of organic chemistry are easier to teach to someone who has never seen organic chemistry. And so – yes, they get excited. They get that feeling, “I am learning and doing organic chemistry two to three years before I am supposed to learn it.” And that is rewarding. It is a lot of fun.

Many students do not pursue a career in chemistry. They go to medical school, for example. For me, it is not about turning everybody into a chemist but teaching them to have an understanding and respect for chemistry. When I go and visit a doctor, for example, they ask me what I am doing and I say I am a chemist, and very often they say: “Oh, chemistry – that was hard when I was in college.” The more we can get away from that, the better it would be for everyone. That is the challenge and the satisfaction of working with younger students.

Do you have an easy starting tip for somebody who wants to get better at communicating science to people who are not involved in science?

There are lots of ways in which I can get people interested in chemistry. It is not really through stamps. I have also in my office a collection of elements. I have about 55 different samples of elements. That is one way to reach out to different audiences. Those are an excuse to develop a conversation about chemistry.

Before the pandemic, once a year we had a big science and technology expo in the state of North Carolina. This is open to the public. We always have a table there where I bring my collection of elements. Most of the elements are safe to touch, so they can be handled by the audience. You can see very young kids who are amazed by the elements. That is I think the key for anyone to be able to communicate science: You have to have a tool. Whether that tool is a collection of elements or stamps or some experiments, something that is easier to see, to understand, to be attracted to, to use your senses, to make you see what the connections to hardcore science are. It is not through talking about formulas and mechanisms that you will get people hooked on science or chemistry. It is by building stories about what is it that we do besides working in the lab, about what fascinates us every day.

You never know what the people you are reaching out to will be doing 10 or 20 years from now. Maybe they will be the next Angela Merkel. I could argue that the world has enough chemists and not enough people who understand and value and respect chemistry. That we need a lot more than just producing more and more chemists.

That is very wise and fits very well into these times.

Thank you very much for the interview.

Daniel Rabinovich, born in Peru, studied chemistry at the Catholic University of Lima, Peru, and earned his Ph.D. in inorganic chemistry from Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, in 1994. After postdoctoral work at Los Alamos National Laboratory, NM, USA, he joined the Department of Chemistry at The University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he is currently a professor of chemistry.

He served as Chair of the American Chemical Society (ACS) Division of the History of Chemistry (2019–2020), is a regular contributor to Chemistry International, the IUPAC quarterly news magazine, and is interested in science communication and the use of postage stamps as teaching tools.

Selected Publications

- L. S. Maffett, K. L. Gunter, K. A. Kreisel, G. P. A. Yap, D. Rabinovich, Nickel Nitrosyl Complexes in a Sulfur-Rich Environment: the First Poly(mercapto-imidazolyl)borate Derivatives, Polyhedron 2007, 26, 4758-4764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poly.2007.06.024

- T. A. Pinder, D. VanDerveer, D. Rabinovich, Lead(II) in a Sulfur-Rich Environment: Synthesis and Molecular Structure of the First Dinuclear Bis(mercaptoimidazolyl)methane Complex, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2007, 10, 1381–1384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2007.08.015

- D. Rabinovich, The Allure of Aluminium, Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 76. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1535

- G. E. Tyson, K. Tokmic, C. S. Oian, D. Rabinovich, H. U. Valle, T. K. Hollis, J. T. Kelly, K. A. Cuellar, L. E. McNamara, N. I. Hammer, C. E. Webster, A. G. Oliver, M. Zhang, Synthesis, Characterization, Photophysical Properties, and Catalytic Activity of an SCS Bis(N-heterocyclic thione) (SCS-NHT) Pd Pincer Complex, Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 14475–14482. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4DT03324H

- M. W. Kimani, D. Watts, L. A. Graham, D. Rabinovich, G. P. A. Yap, J. L. Brumaghim, Dinuclear Copper(I) Complexes with N-Heterocyclic Thione and Selone Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization, and Electrochemical Studies, Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 16313–16324. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5DT02232K

- D. Rabinovich, Synthetic Bioinorganic Chemistry: Scorpionates Turn 50, Struct. Bond. 2016, 172, 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/430_2015_212

- D. Rabinovich, Remembering Henry Moseley, ACA RefleXions Spring 2019, 54. Link

- D. Rabinovich, IYPT and the Mother of All Tables, Chem. Int. 2019, 41(4), 60–61. https://doi.org/10.1515/ci-2019-0433

- D. Rabinovich, International Year of the Periodic Table (IYPT): A Midyear Philatelic Report, Phil. Chim. Phys. 2019, 40, 56–65.