A study showing parabens are present in breast tumor tissue was quickly picked up by the tabloid media, but was their reporting accurate?

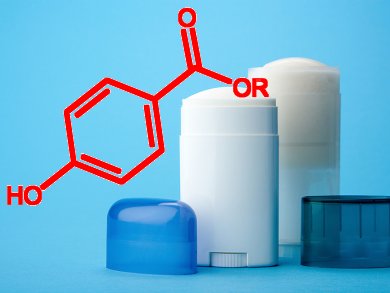

Parabens are used as preservatives in deodorants and antiperspirants as well as cosmetics, foods, and drugs. They are alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid and their salts and have potent antibacterial and fungicidal properties. However, some people suggest that we should not be smearing these substances on our skin nor eating them. However, there is a general feeling among the public and in activist groups that consumers should not be smearing any synthetic substance on their skin nor eating them for unfounded and unproven risks to health. When a study appears hinting at their detrimental effects the tabloids quickly publish their scare stories.

Research on Parabens

In the early 2000s rumors about parabens circulated, but a 2002 epidemiological study by Mirick and colleagues, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, USA, [1] compared 813 women with breast cancer and 793 women without the disease and found no link between breast cancer risk and underarm shaving or deodorant use. In 2003, Kris McGrath of Northwestern University, USA, [2] questioned women with breast cancer and asserted that underarm shaving and deodorants had lowered the average age of onset. Then, Philippa Darbre of the University of Reading, UK, and colleagues [3] reported the presence of parabens in breast cancer tumors. I reported on these findings in June 2004 [4].

At the time, Darbre and colleagues suggested that the presence of unmetabolized parabens in a small group women tested meant that the compounds had been absorbed directly through the skin. The research did not say definitively whether the residues were from the many foods, drugs, and cosmetics that include them. Moreover, it said nothing about whether the presence of parabens was linked to the development of breast cancer. Indeed, a 2005 review by Robert Golden and co-workers [5], University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA, concluded that “it is biologically implausible that parabens could increase the risk of any estrogen-mediated endpoint”. The same review suggested that exposure to natural estrogen mimics represented a far greater risk.

A 2008 systematic review by Moïse Namer and colleagues, Nice University of Medicine, France, [6] looked at 59 research papers on this topic searching for a putative link between breast cancer and parabens-containing antiperspirants. It concluded that: “no scientific evidence to support the hypothesis was identified and no validated hypothesis appears likely to open the way to interesting avenues of research”. The authors even suggest that: “it seems possible to affirm that this question does not constitute a problem of public health and that it appears therefore useless to pursue the research on the subject”.

Parabens and Personal Care

“Parabens are still the most widely used preservative in cosmetic and personal care products because formulations preserved with parabens cause fewer skin reactions than other preservatives”, Colin Sanders, a cosmetic chemist who blogs at Colin’s Beauty Pages, based in Petworth, UK, told ChemViews magazine. However, Sanders also points out that, “Bizarrely enough, antiperspirants generally don’t need to be preserved. A few contain very low levels of parabens, but most don’t have any kind of preservative”.

So, why does the issue persist? Science is never definitive, so scientists are reluctant to make definitive statements, they will always concede that there is a finite risk no matter how small. Indeed, the American Cancer Society in its FAQ falls short of being definitive despite the overwhelming evidence: “So far, studies have not shown any direct link between parabens and any health problems, including breast cancer”. It qualifies this assertion: “The bottom line is that larger studies are needed to find out what effect, if any, parabens might have on breast cancer risk”. Scientifically sensible, but ambiguous enough for any tabloid hack to mangle.

Two Sides to Every Story

It was inevitable that a paper published in the Journal of Applied Toxicology [7] and reported on by ChemViews magazine [8] would be thus mangled. The Daily Mail, for instance, said that: “Chemical found in deodorants, face cream and food products is discovered in tumors of ALL breast cancer patients”, while The Sun quoted lead author, Philippa Darbre, as saying: “I ditched my deodorant to lower risk of breast cancer”.

I asked Darbre about this point, which underpins her research motivation. “I gave up using underarm cosmetics about 15 years ago”, she told me. “This was because I wanted to know whether these products were essential to life. My grandmother and mother lived without them.” When it was brought to her attention that the underarm area is adjacent to the region of the breast where more than half of breast cancers start, she reasoned, it was time to investigate. “I had to know if there were a problem ever identified, that women could act preventatively by simply stopping using [underarm products],” she says.

Her Journal of Applied Toxicology study [7] is based on samples from just 40 women with breast cancer, a small number from which to draw big conclusions. Moreover, no samples were taken from an equivalent number of women without breast cancer; so there was no control group for the study. I asked Darbre about this issue too and she pointed out that it is difficult to obtain breast samples from healthy women. “I have no reason to hypothesize that the amounts of parabens would be different,” she told us. “For me, the issue is that parabens can get into the human breast and it is clear that there were very varied levels within the grouping that we studied. I have no doubt that susceptibility of individuals will play an important role alongside total loading simply by analogy with the issue that not everyone who smokes gets lung cancer.”

Darbre and colleagues found that almost all the samples (160 in total from the 40 women) had traces of at least one parabens and about two-thirds contained five different parabens. Intriguingly, patients who reported never having used underarm deodorant also had traces of these compounds in the breast tissue. “Trying to get accurate information on quantity and type of product usage is fraught with issues of recall and historical usage and we felt that identifying women who could say they had never used underarm cosmetics would be one indisputable piece of information,” Darbre told us. An earlier study by Larry Needham and co-workers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, showed in 2010 that parabens are apparently ubiquitous in urine samples, based on testing during 2005–2006 of 2548 samples [9]. That would suggest that it is going to be almost impossible to disentangle any link with any disease.

Debunking the Headlines

NHS Choices, an online magazine produced by the UK’s National Health Service, frequently debunks the tabloid headlines as related to medical matters and was quick to unravel this story. The magazine points out that the researchers themselves conclude that the presence of parabens in breast cancer tissue samples does not prove that parabens cause breast cancer; the tabloid headlines were nonsense. “Many factors are known to increase the risk of breast cancer, and as the researchers conclude, it is unlikely that any single chemical would be a dominant risk factor,” says NHS Choices.

Looking at Research

In more than a decade of research that has looked for a link, the overwhelming scientific consensus is that parabens are totally unconnected with breast cancer incidence and that further research into this notion really is unwarranted. “To my knowledge there have only ever been two studies measuring parabens in breast tissue — our paper in 2004 and this second one in 2012 [3, 7]. It takes a long time to do these things,” adds Darbre.

“It doesn’t seem very likely that parabens would cause breast cancer,” adds Sanders. “A couple of them are weakly estrogenic. The trouble is that if you ask the question ‘are parabens safe?’ we don’t have enough information to say definitely yes. But that isn’t the question that the people researching cancer would ask. They would start by asking which factors are most likely to cause cancer. If you look at it from that point of view, what case is there for looking at parabens? Not very much really.”

There are many other, much stronger estrogen mimics to which we are exposed in far greater quantities than parabens, especially in our food. “It is easy to write a story knocking a particular chemical, but if that diverts research away from the most profitable areas to work in it could delay the development of effective treatment,” Sanders adds.

It is an irresponsible tabloid media that has a disproportionate response to an iterative research study especially given that the studies themselves are small-scale, take a long time, and are inconclusive. It makes one realize, once again, that there is a potent chemophobic agenda at play — not to improve our health, but simply to sell more newspapers. Unfortunately, it preys on the fearful and feeds a cottage industry of misplaced activism against risk, however small, in preference to addressing serious health problems.

References

[1] D. K. Mirick, S. Davis, D. B. Thomas, J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94(20), 1578–1580. DOI: 10.1093/jnci/94.20.1578

[2] K. McGrath, Eur. J. Cancer Prevent. 2003, 12(6), 479–485. DOI: 10.1097/00008469-200312000-00006

[3] P. D. Darbre, A. Aljarrah, W. R. Miller, N. G. Coldham, M. J. Sauer, G. S. Pope, J. Appl. Toxicol. 2004, 24(1), 5–13. DOI: 10.1002/jat.958

[4] D. Bradley, SpectroscopyNOW 2004. Link

[5] R. Golden, J. Gandy, G. Vollmer, Critical Rev. Toxicol. 2005, 35(5), 435–458. DOI: 10.1080/10408440490920104

[6] M. Namer, E. Luporsi, J. Gligorov, F. Lokiec, M. Spielmann, Bulletin du Cancer, 2008, 95(9), 871–880. DOI: 10.1684/bdc.2008.0679

[7] L. Barr, G. Metaxas, C. Harbach, L.-A. Savoy, P. Darbre, J. Appl. Toxicol. 2012. DOI: 10.1002/jat.1786

[8] Parabens in Breast Tissue, ChemViews Magazine 2012. DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201200011

[9] A. M. Calafat, X. Ye, L. Y. Wong, A. M. Bishop, L. L. Needham, Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118(5), 679–685. DOI: 10.1289/ehp.0901560

Also of interest:

P. D. Darbre, J. Appl. Toxicol. 2006, 26(3), 191–197. DOI: 10.1002/jat.1135