New Entrepreneurship Culture

Innovative High-Tech start-ups are all the rage. They drive innovation and challenge current market structures with new approaches. We are speaking of a new entrepreneurship culture and a boom in innovative company flotations, in Germany in particular in Berlin. However, the chemistry industry is not caught up in this trend. Based on the numbers from the German Private Equity and Venture Capital Association (Bundesverband der Kapitalbeteiligungsgesellschaften, BVK) only 0.9 % of venture capital investment ended up in the chemistry/materials sector. Furthermore, High-Tech Gründerfonds (HTGF) Germany’s most active early-phase funder, only provided 3.4 % of its investments in the chemistry and new materials sector. According to the German Chemical Society (Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker; GDCh), only about 4 % of chemistry graduates start their own company or become self-employed.

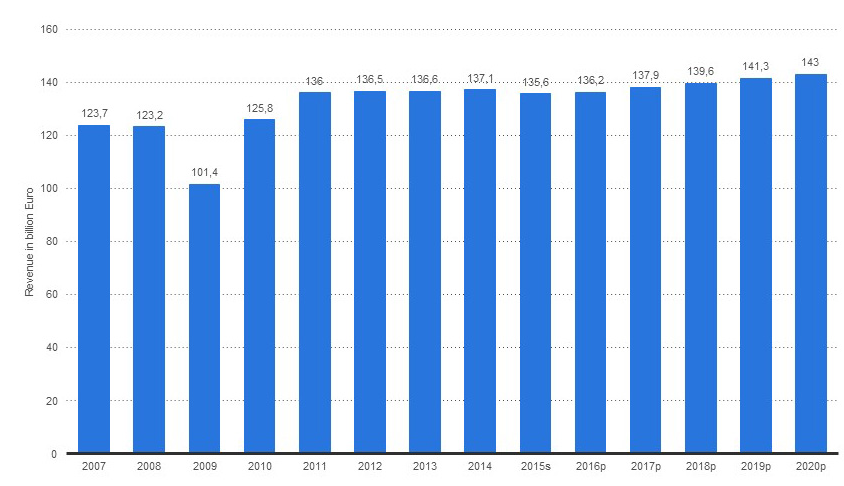

This is despite Germany’s chemistry industry being champions in export and Germany being the coutry with the third best turnover. Based on statistics data, two thirds of turnover is from overseas trade. To maintain this competitive advantage, a strong sense of innovation is required. The German chemical industry association (Verband der chemischen Industrie; VCI) warns that turnover is static and the sector has difficulties in holding on to its strong position. This is made obvious in Figure 1. Predictions for growth in turnover up to 2020 are also only moderate. Demand from growth nations such as China, Brazil, or Russia is decreasing, energy costs are too high, and market confidence is decreasing. At the same time, competitors in the USA or Asia are investing heavily in research and development.

Figure 1. Forecasted sales development in the chemical industry in Germany from 2007 to 2010. (Sources: Statista (own calculations); Federal Bureau for Statistics (Statistisches Bundesamt); VCI)

Innovative Strength of the Chemical Industry

Germany still remains one of the strongest centers in the world for research. According to the VCI, the German chemical and pharmaceutical industry invests more than €10B each year in research and development. The chemical industry is a driving force for innovation in other sectors, and strong innovation is key to increased competitiveness. Indeed, the chemical industry features a high degree of automation. An increase in product and process quality and improvements in connectivity have been driven forward through “Industry 4.0”. However, only about half of the companies involved in the chemical industry use the Industry 4.0 applications.

Furthermore, internal company innovation structures are seen to be a significant obstruction to new development. Too often, there is a sceptic or objection raiser at an important position in a company who delays or stops a new idea. A high degree of specialization in departments and companies is often responsible; increasingly, innovations arise at the boundaries of biology and information technology. The themes of Industry 4.0 and digital transformation are decisive innovation factors, and speed and flexibility are required.

Lateral Thinkers

We, therefore, need more lateral thinkers who can assert themselves entrepreneurially and drive forward new ideas with a readiness to assume risk. Start-ups can take up this role. They can go down completely new paths so as to adjust to changing market conditions and customer needs and to turn a stale business model on its head. The investors are ready to assume a risk and expect just that. Disruptive innovations can be of considerable value from a financial and corporate viewpoint.

This can be attractive for start-ups and investors. The sector is actively searching for innovations and new areas of business. This also drives company takeovers and fusions. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) talks of a takeover fever, noting a mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transaction amount of US$ 137.7B in the first half on 2016 alone.

Thus innovative company flotations have a strong breeding ground and good prospects.

Hurdles for Entrepreneurs in Chemistry

On the other hand, chemistry start-ups have to deal with many obstacles. In many cases the required capital is high. Research and development is very costly, and expensive plants are required for production. In addition, the path to a marketable product can be long: New materials are often located right at the start of the value chain and have to be integrated into the developmental work of new products or changes to products. Market penetration can take a long time. Furthermore, the licencing and approval process can take years. Many start-ups cannot emerge from the pototypical phase.

.png)

Figure 2. Obstacles to innovation of start-ups in the chemical industry in 2015 (Sources: Statista; IW Köln; various sources (Santiago))

If start-ups carry out service contracts for larger companies, the intellectual property (IP) usually remains with the customer and only rarely with the start-up. A company is, however, only truly valuable when it offers its own products and its own IP. Companies offering innovative services thus have difficulties in finding investors. Figure 2 shows the greatest hurdles to innovation for chemistry start-ups.

The frequently mentioned barriers and obstacles for flotations in general and in the chemistry sector in particular, which stand in opposition to the otherwise good terms for chemistry companies, such as lack of capital, bureaucracy, not enough guidance, not enough networks could be overcome, or even better, circumvented.

Many areas of innovation in chemistry involve new software to help solve specific problems. Enzymes, additives, bacteria, and biochemical applications can lead to good business on a small scale. If this leads to applications on a large scale, many established companies are ready to act as partners. From Germany as the leading exporter, these partners can carry the innovations out into the world and define new standards.

Chemists Prepared for Risk and Support

The real bottleneck lies however in the entrepreneurial culture of the sector. Many chemists shy away from risk and would rather have a permanent position than to become self-employed. Starting with universities, there is a lack of entrepreneurial courses or excursions to successful chemistry start-ups. Many investors desire more companies that are on the way to boldly implement ideas from (university) research or from a large company. If very good ideas that are discovered by scientists are not matched with the right companies, business angel networks or seed fonds, like High-Tech Gründerfonds, help to bring both together.

We, therefore, recommend researchers with ideas and also companies looking for an idea to seek out these institutions and networks. Often chemists lack the business skills and marketing and sales knowledge. The above-mentioned institutions can assist with completing management and opening doors to further investors and established companies. From this, valuable development projects, customer-supplier relationships, or investment opportunities can be established for the company. This is a win-win situation for the established chemistry industry, which requires innovations for competitive advantage, and for the chemistry start-up, which thus gains access to the infrastructure and networks of the estanlished company.

Apart from seed fonds, before flotation, start-up programs such as EXIST or GoBio can bridge the first hurdles up to flotation financially. Taking part in business plan competitions such as Science4Life or pitch events can also be a first step to establish whether the technology or business model persuades potential investors. High-Tech Gründerfonds stages pitch days several times every year for both chemistry start-ups and for chemistry-related fields in life sciences. If this first step to an investment is a success, seed fonds can also help in the procurement of experts that can assist in the often very complicated licensing and approval processes. It only needs the first step to be taken towards entrepreneurship – be bold!

|

Stefanie Zillikens holds a degree in nutrition science (Dipl. Oec.troph.) from the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Germany. From 2001–2008 she was Communications Expert (service provider for agriculture and nutrition) at ZMP GmbH Bonn, Germany, from 2008–2011 Marketing Specialist (HR services) at adevis Personalkultur GmbH Cologne, Germany, and supervisory board member (HR-networking) at persolinus AG, Karlsruhe, Germany. Currently, Zillikens is Head of Public Relations of High-Tech Gründerfonds, Bonn, Germany. |

|

Michael Brandkamp studied economics at the Universities of Münster, Germany, Nairobi, Kenia, and Bonn, Germany, and obtained his PhD at the Technical University of Freiberg, Germany, on Technologies for Innovative Start-up Enterprises. From 1999–2004, he was Head of the Berlin office of tbg Technologie-Beteiligungs-Gesellschaft mbH, from 2001–2004, Assistant Managing Director of tbg, and from 2004–2005, he was Departmental Director for Innovation Financing and Investment within the KfW Banking Group. Currently, Brandkamp is Managing Director of the High-Tech Gründerfonds, Bonn, Germany. |

Also of Interest

- Chemistry Drives Innovation,

Vera Köster, Thorsten Daubenfeld,

ChemistryViews 2016.

https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.201600016

Entrepreneurship in chemical training and importance of start-ups for innovatio - Javier García-Martínez on the Commercialization of Research,

Javier García-Martínez, Vera Köster,

ChemistryViews 2012.

https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.201200143

How do you form a spin-off company from your research? J. García-Martínez talks about his experinces and how he finds time for his many roles - How to Become an Academic Entrepreneur,

Vera Koester,

ChemistryViews 2014.

9 tips to successfully turn discoveries into an everyday reality