After having looked at saccharin’s invention and the subsequent battle for credit for the synthesis, we examine the challenges of the early industrial production and the organized smuggling that sprang up in Europe to circumvent import restrictions.

4. Battles over Saccharin

4.1. Industrial Production of Saccharin

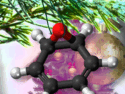

Production of saccharin in the United States on an industrial scale failed over high costs for both wages and raw materials. Building a factory in Leipzig, home of Adolph List, prosperous businessman and uncle of the chemist Constantin Fahlberg, was also out of the question due to associated odor pollution. So the first saccharin factory in the world was built elsewhere in Germany, in Salbke near Magdeburg on the river Elbe. It was a convenient site from a transport point of view, since it was between the highway linking Magdeburg with Schönebeck, and the rail line Magdeburg–Leipzig. Production commenced here on March 9, 1887 (see Fig. 6).

|

|

|

Figure 6. The world’s first saccharin factory. Left: View of the factory grounds of Fahlberg, List & Co. in 1887. Right: The same view in 1893. In only six years, the number of buildings had increased five-fold [14,15]. |

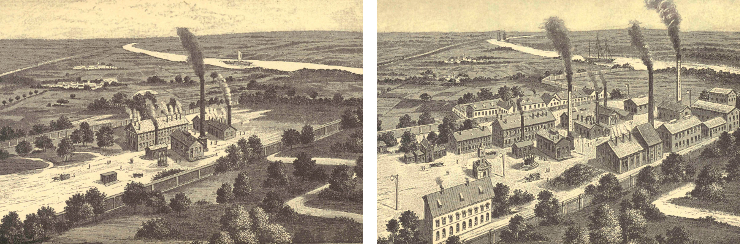

Fahlberg’s industrial approach to saccharin began with toluene (6), which upon sulfonation with sulfuric acid led to a mixture of ortho– and para-toluenesulfonic acids (1 and 7). This mixture was then transformed into the sulfonyl chlorides 8 and 9 using phosphorus pentachloride. Separation of the two isomers seemed easy, since ortho-toluenesulfonyl chloride (8) is a liquid, whereas the corresponding para-compound (9) is a solid. In the early years of production, no one recognized that the resulting saccharin (5) was in fact contaminated with p-sulfamoylbenzoic acid (10) to the extent of 40 % (see Fig. 7) [14, 15].

|

|

|

Figure 7. So-called “pure” saccharin was refined chemically. |

In 1891, Fahlberg introduced an extra purification step, in which the supposedly “pure” saccharin (actually a 3:2 mixture of 5 and 10) was first treated with an alkaline solution. The pK values of p-sulfamoylbenzoic acid (10) (pK = 3.6) and saccharin (5) (pK = 2) differ significantly, so the stronger acid (saccharin) dissolved, while the byproduct 10 remained insoluble.

Introduction of this additional purification step resulted in a truly pure end product, which was subsequently marketed as “raffinated” saccharin. Removal of the non-sweet impurity (10) increased the sweetness factor from 300 in “pure saccharin” to 550 in raffinated saccharin.

|

|

|

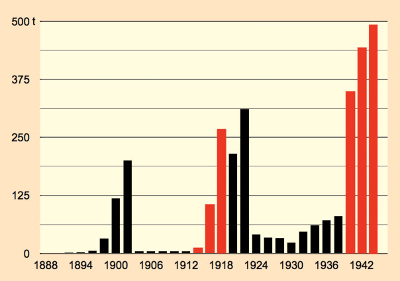

Figure 8. Annual saccharin consumption in the German Empire. |

As a result of its initial “monopoly” position, Fahlberg, List & Co. succeeded in maintaining a steep market price of 150 Reichsmark (RM)/kg. Sales skyrocketed (see Fig. 8). This of course aroused the interest of potential competitors, who soon edged their way into the market. For cost reasons, attempts were made to skirt around the production methods patented by Fahlberg (see Fig. 9). The von Heyden chemical company in Radebeul, Germany, succeeded in converting toluene with chlorosulfonic acid directly into toluenesulfonyl chloride.

|

|

|

Figure 9. Industrial syntheses of saccharin. |

Compared to the original synthesis of Remsen and Fahlberg, the von Heyden Chemical Works approach eliminated one step, transforming toluene (6) directly into a mixture of the toluenesulfonyl chlorides 8 and 9 [16]. This more cost-effective process ultimately prevailed, and was in fact adopted in 1906 by Fahlberg, List & Co. as well.

In the 1950s, O. Senn and G. F. Schlaudecker developed an alternative approach starting with methyl anthranilate (11), readily available from phthalic anhydride (12). Diazotization and treatment with sulfur dioxide, chlorine, and finally ammonia led directly to saccharin. This process was adapted for commercial application in the mid-1950s by the Maumee Chemical Company of Toledo, Ohio, USA. It had the major advantage of avoiding the costly separation of ortho– and para– isomers.

4.2. Saccharin for the People

Fahlberg, List & Co. tried in vain to prevent von Heyden from patenting their competing process in a three-year legal battle. As noted above, this alternative synthetic route was more economical, permitting von Heyden to market saccharin at a significant price advantage relative to Fahlberg, List & Co. A merciless price war ensued, in which the kilogram price for saccharin fell in Germany from 150 Reichsmark (1888), through 30 RM (1895) ultimately all the way to 15 RM (1902) [17].

Around 1900, there were several saccharin manufacturers active in the German market. Fahlberg had protected the trade name “Saccharin” in 1896, so competing companies were forced to market their chemically identical products under different names, e.g.:

- Saccharin: Fahlberg, List & Co., Salbke

- Zuckerin, Crystallose: Chemische Fabrik von Heyden, Radebeul

- Sucrin, Sycose: Farbenfabriken Bayer, (formerly Friedr. Bayer & Co.), Elberfeld

- Süßstoff Höchst: Farbwerke Hoechst, (formerly Meister, Lucius & Brüning), Hoechst

- Sycorin: Straßfurter Chemische Fabrik (formerly Vorster and Grüneberg)

By 1901, the von Heyden Chemical Company was responsible for the greatest market share (47.9 %), followed by Fahlberg, List & Co. (31.8 %), Hoechst (10.7 %), Bayer (6.3 %), and Straßfurt (3.5 %). In 1932, Fahlberg, List & Co. released its rights to the trade name “Saccharin” in exchange for a compensatory payment, so the name could subsequently be used by any manufacturer.

4.3. The Sugar Barons Make Their Appearance

Although saccharin was six times as expensive per kg as sugar, it was 550 times as sweet. Thus, based on a comparable sweetness, saccharin was 100 times more economical. It is no wonder that saccharin’s market success upset the beet-sugar industry. In its own interest, the sugar industry thus managed to limit the market for saccharin in most European countries. In Spain, Belgium, and France it could legally be dispensed only for pharmaceutical and medical applications, and since 1898, import of saccharin into Austria, including Bohemia, was forbidden entirely.

.jpg) At the end of the 19th century, the German Empire was the chief exporter of sugar worldwide, and the sugar industry was correspondingly powerful. In July, 1898, it succeeded in arranging for the adoption of the “1st Sweetener Statute”. The statute – apart from introducing a labeling requirement – forbade any use of saccharin in many foods produced in large quantities completely (see “The Five German Saccharin Statutes“).

At the end of the 19th century, the German Empire was the chief exporter of sugar worldwide, and the sugar industry was correspondingly powerful. In July, 1898, it succeeded in arranging for the adoption of the “1st Sweetener Statute”. The statute – apart from introducing a labeling requirement – forbade any use of saccharin in many foods produced in large quantities completely (see “The Five German Saccharin Statutes“).

From a present-day point of view, such limitations might be regarded as eco-friendly, but at the time, nothing but economic interests stood behind them. The sugar industry wanted only to keep competitors off its back. Fahlberg thus complained, for example, about the legal prohibition against sweetening wines with saccharin [14,15]:

|

“My suggestions have frequently been ignored about how to make old, sour wine palatable; the puritanical majority in the Reichstag has shown, through the most recent wine laws, no understanding of the situation, since use of saccharin in wine has been utterly forbidden.” |

It soon got even worse, however, because the 1st Sweetener Statute was insufficient to hold back the success of saccharin. In 1901/02, sugar suffered a major marketing crisis worldwide, while German annual production of saccharin exceeded 200,000 kg, coupled with a new minimum price of 12 RM/kg. Based on sweetening power, this quantity corresponded to 5 % of German sugar consumption. Soon, the political heavyweights of the beet-sugar industry were really up in arms, and they succeeded in forcing a virtual prohibition of saccharin.

Despite the opposition of both the Progressive Party (Freisinnige) and the Social Democrats, after a turbulent debate – in which the Progressive delegate Dr. Otto Hermes (zoologist and director of the Berlin Aquarium) shined with respect to his knowledge of chemistry – the German Parliament, the Reichstag, adopted a 2nd Sweetener Statute (for details see “The Turbulent 191st Session of the German Reichstag“). Under its terms, Fahlberg, List & Co. was designated as the exclusive licensed dealer for saccharin on the German market, but even so the product could be sold only in pharmacies, and then only by prescription and at a government regulated fixed price. In 1901, 170 tons of saccharin were still produced, but this fell in 1903 to 3–5 tons. In the year after the saccharin ban, incidentally, the price for sugar increased by 23 %.

Despite the opposition of both the Progressive Party (Freisinnige) and the Social Democrats, after a turbulent debate – in which the Progressive delegate Dr. Otto Hermes (zoologist and director of the Berlin Aquarium) shined with respect to his knowledge of chemistry – the German Parliament, the Reichstag, adopted a 2nd Sweetener Statute (for details see “The Turbulent 191st Session of the German Reichstag“). Under its terms, Fahlberg, List & Co. was designated as the exclusive licensed dealer for saccharin on the German market, but even so the product could be sold only in pharmacies, and then only by prescription and at a government regulated fixed price. In 1901, 170 tons of saccharin were still produced, but this fell in 1903 to 3–5 tons. In the year after the saccharin ban, incidentally, the price for sugar increased by 23 %.

Since 1901, Fahlberg, List & Co. itself undertook it to produce the sulfuric acid required for saccharin synthesis, using the relatively new “contact method” under license from BASF [17]. The resulting sulfur trioxide could be used to make chlorosulfonic acid, which in turn allowed Fahlberg, List & Co. to take advantage of the more economical Heyden route to saccharin. This all proved to be fortunate, since within a relatively short time the profits from sulfuric acid manufacture actually exceeded those from saccharin, which allowed the company to cope with the drastic reduction in saccharin demand resulting from the 1902 Sweetener Statute.

Other companies engaging in saccharin manufacture also managed quite well, despite the statute. They were compensated for revenue losses from domestic operations. Furthermore, the manufacturing ban applied only to saccharin itself. Thus, the last synthetic step prior to saccharin, leading to o-toluenesulfonamide, was not affected, so Von Heyden leased a chemical factory in Nidau on Lake Biel in the Swiss Canton of Bern [19], where they carried out only the last synthetic step, the oxidation with permanganate.

Other companies entered the saccharin business as well, even if only indirectly. BASF developed an economic synthesis of their own for o-toluenesulfonamide, becoming the leading producer of this saccharin precursor. BASF was especially successful in dealing with Russia, since the saccharin precursor could be exported there without limit.

5. Saint John of Nepomuk Makes an Appearance

Most European countries protected their national beet-sugar industries by imposing high saccharin taxes and import limitations. But in the middle of Europe around 1910, there was one country in which not only as much saccharin as desired could be produced, but in addition that saccharin was not subject to taxation. Moreover, imported sugar was not burdened with high taxation. This sweet European oasis was Switzerland. Low sugar prices effectively supported the local chocolate industry, andat the same time, the lack of sweetener taxes helped the young Swiss chemical industry (Sandoz, CIBA) to a cheap blockbuster, one that played an important role in the economic ascent of these firms.

The Swiss tax oasis, with its high production of saccharin, surrounded by countries with many potential customers (Germany, Russia, and Austria, including Bohemia) where all saccharin import was prohibited – these were ideal conditions for smuggling, whether on a large or a small scale [20]. The Swiss regularly “sweetened” letters and parcels destined for friends and relatives outside the country with small gifts of saccharin. This brought sweet pleasure to the recipients, and the senders gained no less sweet Schadenfreude from having outwitted the customs authorities in some other country.

Many ordinary people in the borderlands managed to cover their saccharin requirements via smuggling. Since most customs agents on the Swiss side could hardly have cared less, and since those in neighboring states were basically helpless because of the long borders, large amounts of saccharin made their way across the Swiss border, hidden in clothing or dissolved in champagne bottles.

In contrast to other neighboring countries, there were very few easy routes over the border between Austria and Switzerland, and these were tightly controlled by Austrian customs agents. Professional smugglers had to apply considerable intellectual effort to successfully transport saccharin directly from Switzerland into Austria. For example, one gang developed the following remarkable method, on the basis of a solid knowledge of acid-base theory:

The smugglers began in Switzerland by dissolving saccharin (not its sodium salt!) in a little ether, and stirring the concentrated solution into molten wax. From this melt, large altar candles were poured, which then were consecrated in the Einsiedeln Abbey (Canton Schwyz). As devotional objects, the candles passed easily and unimpeded over the border into Austria.

In Vienna, they were melted down again in a shop specializing in devotional objects (and opened specifically for that purpose). The molten material was treated with dilute, aqueous sodium hydroxide, causing saccharin to be converted quantitatively into its sodium salt, which passed into the aqueous phase. The wax floated to the top, so it could be readily separated and reutilized for the next batch. Addition of hydrochloric acid to the aqueous solution caused pure saccharin to precipitate. Apart from a little sodium chloride, there was no chemical waste, so this smuggling operation was truly exemplary: both “sustainable” and “green”. It was successfully pursued for several years, until Austrian customs finally smelled a rat: overcoming their religious inhibitions, they melted down one of the consecrated candles and examined it more closely.

|

But the creative residents of Bischofsreut in Bavaria, Germany, developed a saccharin-smuggling method that relegated all others to the shadows, and above all remained undiscovered. Not until years after saccharin smuggling was passé did this scheme become a subject of discussion. At the center of the operation stood St. John of Nepomuk, patron saint of Bohemia, Bavaria, and confessional secrets.

For years, every two weeks, the Bischofsreuters carried a hollowed-out life-sized wooden statue of Saint John of Nepomuk stuffed full of saccharin in a supplicatory procession to Böhmisch-Röhren, then a part of Austria, but now incorporated into the Czech Republic as the village of “Ceské Zleby”. Here the saccharin would be removed and sold for a profit. What St. Nepomuk had hidden under his cloak was never discovered, and no one in the village was ever punished. For this reason, in 1960 they honored their “Saccharin-Nepomuk” with a small private chapel, in which he continues to raise his hands in protective fashion over the inhabitants of Bischofsreut.

The massive amounts of saccharin confiscated over the years by the German customs agents were never destroyed, but instead sold (for 1–3 RM per kilogram) to the licensed monopolist Fahlberg, List & Co. The proceeds flowed into the state coffers, and the saccharin itself was sold for a second time [19]. Since at least some of the confiscated saccharin stemmed from their factory in Salbke, this contradicted the ancient business wisdom that goods could only be sold once. Fahlberg, List & Co. sold a great many saccharin molecules twice!

6. Comeback of the Saccharin Industry

Saccharin smuggle blossomed well into the First World War [21]. Outbreak of the war altered the roles of sugar and saccharin in fundamental ways, however: acreage devoted to sugar beets was drastically reduced, in the interest of potatoes and grain. The German sugar-beet harvest in 1915 was so catastrophically poor, that it was necessary to ration sugar, and in the “hunger years” of 1917 and 1918 sugar could be dispensed only upon presentation of ration coupons. As early as 1916 the Second Sweetener Statute of 1902 was suspended, and both Fahlberg, List & Co. and von Heyden were asked to ramp up their saccharin production. Overnight, the same politicians who a few years earlier had demonized saccharin, suddenly praised it as a gift from heaven.

After the end of the Second World War, the IG-Farben Industry Leverkusen plant (the future Bayer AG) was granted the first license for German saccharin production. Other licenses followed, including to both Casella and Hoechst in Frankfurt. In the early post-war years, incidentally, blue-collar workers at Hoechst received, as a gift from the company, special supplies of saccharin for their personal use.

In the Russian occupation zone, plants and manufacturing equipment belonging to von Heyden were dismantled and shipped as “reparations” to the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, Fahlberg, List & Company found itself unable to obtain sufficient amounts of coal to produce the necessary toluene for full-scale saccharin production, and of the limited amounts of saccharin they did manage to make, most had to be shipped to the Soviet Union. Saccharin ended up in short supply nearly everywhere, such that it became a cherished item for exchange on the black market. At the time of the currency reform in Germany’s three western zones (1948), 38 different artificial sweetener manufacturers had been licensed.

By the early 1950s, ample supplies of sugar were again available on the market, as a result of which sales of saccharin began to decline. Also, in 1957, 1960, and 1961, the parliament of the Federal Republic of Germany (the Bundestag) adopted various modifications to the 5th Sweetener Statute of 1939, until finally, on 1 July 1965, the “sweetener tax” — by this point regarded generally as a “nuisance tax” — was finally abolished.

References

[14] Saccharin, Fahlberg, List & Co., 1893.

[15] Facsimile reproduction by the VEB Fahlberg-List, Magdeburg, Germany, 1980.

[16] Organikum, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2009 (in German). ISBN: 978-3-527-32292-3

[17] H. Rasenberger, Vom süßen Anfang bis zum bitteren Ende, Dr. Ziethen Verlag, Oschersleben, 2009 (in German). ISBN: 978-3-938380-06-2

[18] P. Pries, Gordian 1991, 91, 35.

[19] H. Olbrich, Saccharin, seine Herstellung und Handhabung, Universitätsverlag TU Berlin, 2011 (in German). ISBN: 978-3-7983-2299-8

[20] C. Litz, Dummy 2008, 19, 80.

[21] J. Kuhfuss, Dissertation, University of Gießen, Germany, 1921.

The article has been published in German as:

- Die Saccharin-Saga,

Klaus Roth, Erich Lück,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2011, 45, 406–423.

DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.201100574

and

- Kalorienfreie Süße aus Labor und Natur,

Klaus Roth, Erich Lück,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2012, 46, 168–192.

DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.201200587

and was translated by W. E. Russey.

The Saccharin Saga – Part 1

The invention of the first artificial sweetener and a lifetime battle for credit

The Saccharin Saga – Part 2

The early industrial production and organized smuggling of saccharin

The Saccharin Saga – Part 3

The health concerns associated with artificial sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 4

A glance back to ancient Rome, and the most hair-raising of all sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 5

What’s in your softdrink? – Introducing cyclamate

The Saccharin Saga – Part 6

Aspartame – a sweet dipeptide ester

The Saccharin Saga – Part 7

Acesulfame-K – another successful sweetening agent

The Saccharin Saga – Part 8

Thaumatin – a sweet protein with a licorice aftertaste

The Saccharin Saga – Part 9

Sucrose or Splenda turned into a low-calorie alternative to sucralose or saccharose

The Saccharin Saga – Part 10

Combining sweet cations and anions, and turning bitter compounds into sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 11

Intelligent synthetic strategies for low-calorie sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 12

Stevia plant extracts as low-calorie sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 13

Finding the best mixture of sweeteners to replicate the taste of real sugar

See all articles by Klaus Roth published in ChemistryViews Magazine

.jpg)