After looking at saccharin’s invention and early industrial production, we cover the health concerns associated with artificial sweeteners.

7. America, You Have it Better!

Just like everywhere else, saccharin was introduced in the USA at the start of the 20th century, and treasured – as a sugar substitute for diabetics, for weight reduction in the case of people who were seriously overweight, and as a sweetening agent in food processing.

Not because of saccharin itself, but due to countless other cases of misuse, and sometimes criminal additive introduction, leading to adulteration of foodstuffs and medications, popular political pressure developed. This caused the adoption of a “Pure Food and Drug Act” in the United States in 1906. According to this legislation, preparation and sale of adulterated foodstuffs and medications involving substances hazardous to health was henceforth strictly forbidden. Especially with a view toward the countless and exceptionally popular tonics, it now became obligatory that packaging indicate the presence of the controlled substances alcohol, morphine, opium, cocaine, heroine, or cannabis.

|

The driving force behind this legislation was the chemist Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, who headed the Bureau of Chemistry in the Department of Agriculture, which was charged with monitoring compliance with the new law. Wiley construed the text quite strictly, thereby antagonizing the food industry. For example, Wiley wanted to forbid sweetening of canned corn products with saccharin, because he personally regarded the sweetener as a health hazard. Food processors interceded by way of President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908, urging that the functions of the Bureau of Chemistry be cut back. As a consequence, Roosevelt requested Wiley along with industry representatives to the Oval Office.

Unfortunately, only Wiley’s version of the resulting conversation has survived, though he declared it to be verbatim. Let us therefore assume the role of a little mouse listening in the Oval Office. It is 10 in the morning, and Dr. Wiley is the reporter:

“Theodore Roosevelt gives the floor first to James S. Sherman from Sherman & Bros., a canned corn producer from New York, USA:

|

J. S. Sherman: ‘Mr. President, through use of saccharin in place of sugar for the sweetening of corn, my company saved $4,000 last year alone. It is in this context that we request a decision from you.’ |

Unfortunately I did not wait for the President to pose the usual starting question. I was in much too great a hurry in the matter. I immediately addressed the President, without his first addressing me. For kings and presidents that is an insult. In the presence of senior executives one should always wait to be addressed before jumping into the conversation. Had I remained true to this principle the catastrophe that followed might have been averted. I said at once to the President:

|

H. W. Wiley: ‘Everyone who eats such sweet corn is cheated! He thinks that he is eating sugar, but in truth he is consuming a product made out of coal tar, with no nutritional value, and extremely hazardous to health.’ |

His response marked the beginning of complete destruction of the food legislation. In a rage, the President transformed himself, simply by turning around, from Mr. Jekyll into Mr. Hyde, and said:

|

T. Roosevelt: ‘Are you trying to tell me that saccharin is hazardous to health?’ H. W. Wiley: ‘Yes, Mr. President, that is exactly what I want to say!’ T. Roosevelt: ‘Dr. Rixley (Roosevelt’s physician) gives it to me every day.’ H. W. Wiley: ‘He probably thinks that you might become diabetic.’ T. Roosevelt: ‘Anyone who says that saccharin is harmful to health is an idiot!’ |

This remark from the President terminated the meeting. If he had then pulled out the royal sword Excalibur, the knighthood ‘Idiot’ would probably have been conferred upon me.”

On the very next day, President Roosevelt appointed a Referee Board of Consulting Scientific Experts to evaluate once and for all the health risks associated with saccharin. As chairman of this commission he appointed, of all people, Ira Remsen (see The Saccharin Saga – Part 1, chapter 2), who felt he could hardly turn down this request from the President. Since the commission ultimately was to determine the fate of possible saccharin prohibition in the United States, Remsen found himself in a position that was very difficult for him personally. Remember that Fahlberg had betrayed him, and never suitably acknowledged Remsen’s role in the discovery of saccharin. Fahlberg, List & Co. was by 1908 heavily dependent upon exports into the USA, since the German saccharin market had by law collapsed in the period 1902–1916.

Remsen showed in an impressive way that his powers of scientific judgment rose above any personal antipathy or desire for revenge. After careful consideration and evaluation of all the available toxicological studies, the Remsen Commission came to a unanimous conclusion that saccharin is not injurious to health. Fahlberg, List & Co.’s American market remained intact.

8. America, You Don’t Have it Better After All!

In 1959, the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) conferred GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) Status upon saccharin, a judgment that was to be repeated many times, including in January 1977, in reaction to a news report that “repeated use of saccharin results in no danger”. On March 9, only two months later, however, the same health authority declared a prohibition of saccharin.

What had happened?

At the beginning of March 1977, Marc Lalonde, the Canadian Minister of Health, notified the WHO (World Health Organization) and his colleagues around the world of a study carried out in Ottawa in Canada according to which feeding large amounts of saccharin caused rats to develop cancer of the bladder [22]. To underline his concern, the Minister revealed a timetable for stepwise prohibition of saccharin in Canada. Among other consequences, four months later saccharin-sweetened soft drinks such as calorie-reduced Coca Cola and Pepsi were to be completely banned.

Such political activism on the part of Minister Lalonde was peculiar, especially given that the scientific study to which he referred had not yet been published – indeed, not even completed. The scientists involved in it promptly distanced themselves from the Health Minister’s actions, and rejected the prematurely drawn conclusions, above all the direct application of animal studies to humans.

Such political activism on the part of Minister Lalonde was peculiar, especially given that the scientific study to which he referred had not yet been published – indeed, not even completed. The scientists involved in it promptly distanced themselves from the Health Minister’s actions, and rejected the prematurely drawn conclusions, above all the direct application of animal studies to humans.

But the explanation on the part of the scientists was not heard in the resulting media hysterics. Indeed, the avalanche could no longer be stopped. The American FDA felt compelled to react to Lalonde’s telegram with a saccharin prohibition of its own. There really was no choice, since in 1958, US food legislation had been amended by addition of the Delaney Clause (named for the sponsoring New York Congressman, James Delaney) [23, 24]:

|

“The Secretary of the Food and Drug Administration shall not approve for use in foods any chemical additive found, after intake by man or laboratory animals, or, following appropriate tests for safety evaluation of food additives, to induce cancer in man or animals.” |

The FDA and other US health authorities had long tried to adapt the inflexible wording of the Delaney Clause more clearly to the current state of scientific knowledge. Thus, the suggestion that a carcinogenic substance be excluded if the corresponding risk is essentially negligible (e.g., 1:1,000,000) had already been the subject of considerable legal discussion, despite which American courts had held fast to an “absolute prohibition” in practical case law.

Every effort to invoke a scientifically more reasonable interpretation of the Delaney Clause stumbled immediately on the wording that it:

|

“recognizes no distinctions based on carcinogenic potency and, at least in theory, it applies equally to additives used in large amounts and to those present at barely detectable levels. It thus takes no account of the actual risk that a carcinogenic additive might pose.” |

So, was the Ottowa study “appropriate” in the sense of the Delaney Clause?

Let us look at the actual study more closely. Rats were raised in the course of two generations on a diet that included 5 % saccharin. That would be equivalent to ca. 2500 mg/kg of body weight. In the first generation, 3 of 100 rats developed bladder cancer. In the second generation, which in the fetal state and throughout their entire lives had consumed saccharin, 14 of 100 developed bladder cancer.

The FDA itself pointed out in a press release that a rat consuming 2500 mg/kg would have been subjected to a massive overdose. To approximate this level, a human would, for example, need to drink over 800 bottles of saccharin-sweetened soft drink per day (life-long). By way of comparison, a diabetic replacing sugar intake completely with saccharin would have a daily intake of only 1–2 mg/kg of body weight. In other words, the rats had been fed a quantity more than a thousand-fold in excess of this dose. The saccharin proponents thus turned the tables around. For them, the Canadian study was the best possible proof of spectacular tolerance for saccharin: despite such an absurd overdose, the rats lived to old age. Had they been fed sugar equivalent to only one-tenth of this sweetening power, they would have had only a short life – and one plagued by arteriosclerosis!

This comparison, drawn by saccharin enthusiasts, was of course somewhat clumsy. By extrapolating to an equivalent sweetening power, the amount of sugar involved was so astronomically large that it would already be lethal just from an osmotic standpoint. The acute toxicity of sugar derived from animal experiments would be 20–30 g/kg of body weight, and for saccharin, 14–17 g/kg. By way of comparison, the acute toxicity value for table salt amounts to ca. 4 g/kg body weight.

Another weak point in the Ottawa Study was the laboratory animal itself. Rats concentrate material in their urine to an extremely high degree; i.e., substances excreted in the urine remain at high concentration in the bladder. The combination of an extraordinarily high pH value for rat urine, together with a high concentration of proteins and calcium ions, leads to formation of microcrystals. If these crystals irritate the inner walls of the bladder, this alone can stimulate increased cell division.

Saccharin prohibition was judicially consistent with a strict interpretation of the Delaney Clause, although it contradicted common sense, and it seemed completely excessive in the view of both the American Cancer Society and the American Diabetic Association. For the Americans, it also represented something of a “déjà vu” experience: In 1970, the FDA had also too hastily banned the artificial sweetener cyclamate on the basis of the Delaney Clause. Although it later turned out that this prohibition was not justified, it still persisted for a long time. 80 % of the American public and a majority of the members of Congress were convinced [25] that the 1908 assertion by Theodore Roosevelt remained valid in 1977, namely that “everyone who claims saccharin is harmful is an idiot!”

Americans reacted to the threat of saccharin prohibition in true panic; indeed, with panic buying. Even in Germany, sweetener shelves were emptied by American tourists in the general touristic areas of the Rheinland castles and Bavarian royal palaces. The very soul of the American populace was seething, and by year’s end, the newly elected President Jimmy Carter, members of the House of Representatives, and Senators had all been overwhelmed with roughly a million letters of protest. In 1976 in the United States alone, saccharin consumption reached a market value of 2 billion dollars, mostly through low-calorie food items, and especially low-calorie (“light”) soft drinks.

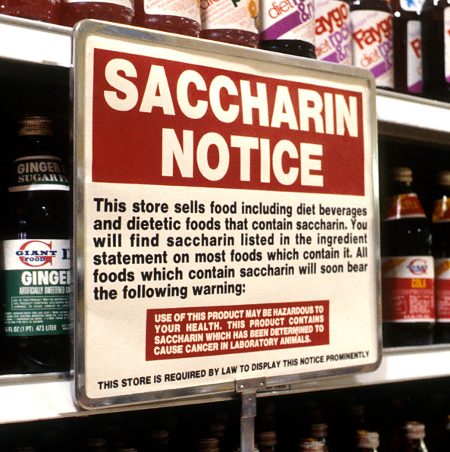

The United States organization “Weight Watchers” represented an enormous vehicle for weight reduction, utilizing both web-based materials and group meetings to promote its stated purpose. Saccharin was (and is) a key element in their success. Women members in particular were responsible for cries of protest when the threat of a strict prohibition of saccharin was announced [26]. The result: on 23 November 1977, application of the Delaney Clause in this specific case was suspended for 18 months (through the Saccharin Study and Labeling Act), although saccharin-containing products were nevertheless required to carry an appropriate warning label (see Fig. 12) during this interim period intended to facilitate further study.

|

|

|

Figure 12. Sweetener warning from USA. |

It was of course naïve to imagine that 18 months would suffice for a definitive conclusion regarding the potential carcinogenic activity of a substance. Countless animal studies had already been carried out, especially in small laboratories, and no harmful consequences had ever been proven. This was to be expected, because saccharin had already been consumed for nearly a century by large segments of the general population, and a comparably vast number of government-ordered studies had already been carried out. Not one respectable study had been able to prove any risk associated with intake of saccharin. The only way truly new results could possibly have been foreseen was through epidemiological or extended-period studies with primates.

One such extensive epidemiological study had in fact already been reported in 1975, where death certificates of 18,733 victims of bladder cancer were compared with those of 19,709 others who had died from other types of cancer. In both groups, diabetics who had consumed saccharin over the course of many years were identified. The result: there had been no increased risk of bladder cancer among the diabetics who had been subjected to saccharin for years.

Long-term studies on apes are extremely expensive, and, of course, take many years. Moreover, their use has been vocally – and increasingly – condemned by animal-rights activists. Nevertheless, one such study with saccharin was initiated in 1973, involving 20 apes (green monkeys, Chlorocebus sabaeus; rhesus macaques, Macaca mulatta, and other macaques). From the time of their birth, the animals were fed saccharin, at a daily dose roughly 10 times the currently permitted maximum. By the time of the threatened saccharin prohibition, this study had already been in progress for four years, and all the subjects raised on saccharin were apparently as healthy as subjects in an equally large control group. The long-term study was completed in 1997, after 24 years, and the result here was equally clear: saccharin obviously did not lead to bladder cancer in primates [28].

In the end, American consumers triumphed: they were allowed to keep their saccharin. The US Senate in 1977 once again postponed the effective date for its prohibition by several years, to provide even more time for scientific studies. This deadline was repeatedly extended, and finally, in 2000, saccharin was removed from the list of apparently carcinogenic substances. Further, the planned saccharin prohibition, and even requirement of a warning label, were quietly relegated to their graves in 2001.

9. Effects on Europe

The threat of a prohibition of saccharin in America, and the resulting controversy, naturally had its effects in Europe as well. Consumers as well as politicians reflected the uncertainty. Fortunately, nothing analogous to the Delaney Clause generated a need for overly hasty action; discretion was possible. As early as 24 March 1977, the German government reacted calmly to a parliamentary inquiry in the Bundestag [29]:

|

“In the Federal Republic of Germany, saccharin has been studied for years in the Federal Health Department and in the Cancer Research Center at Heidelberg, without any indication of carcinogenic character appearing.” |

In Switzerland, the Presidents of the Medical Commission for the Diabetic Association as well as of the Medicinal-Scientific Section issued the following declaration:

|

” … on the basis of a scientifically indefensible experimental design, and a false interpretation of findings, it has been proposed that (saccharin) be unceremoniously prohibited. Even if it were carcinogenic in humans in large doses, one would still need to ask if, in a sociomedical assessment, the risk of cancer was still much smaller than the risk of atheromatous degeneration of the arteries in those who are seriously overweight, and in diabetics. We believe the latter risk to be more grave, and much more widely distributed.” |

Finally, discussion regarding the health risks ebbed away in both the USA and Europe, and saccharin disappeared from the headlines. In public discussion other voices once again had their say. Thus, organizations of physicians and dentists pointed to the great danger and consequences of excessive consumption of sugar, and recommended saccharin as a tried and tested and also harmless alternative. When in 1982 the fitness wave (initiated by Jane Fonda) broke over Europe, the consumption of artificial sweeteners grew once again. It appeared as though saccharin, identified as food additive E954, again and yet again tested with respect to its effects on the heart and kidneys, had finally made its way into calm, shallow waters. Saccharin would certainly have earned it!

10. Epilogue: What Epilogue?

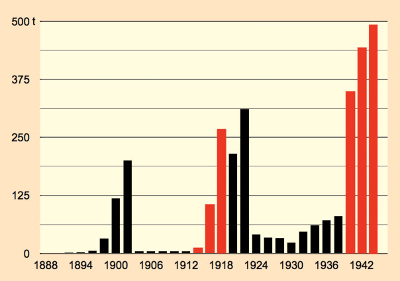

Sales trendlines for products of the chemical industry tend not to class among the most thrilling of graphic displays. This does not actually apply with respect to saccharin, however, because here one sees a diagram of a turbulent history (see Fig. 8, part 2). The constant ups and downs could not simply blow over with saccharin. For one thing, there was always the reputation of a poor-man’s substitute for sugar, while at the same time many consumers sensed a vague concern for a possible health risk. And this despite the fact that saccharin was the most thoroughly investigated food additive ever, demonstrating in countless studies its completely innocuous nature [30].

|

|

|

Figure 8. Annual saccharin consumption in the German Empire. |

Over the long term, saccharin could not entirely overcome prejudices, though, and it apparently passed its peak in the 1980s, as new and unencumbered sweeteners emerged. Especially as a result of their superiority from the standpoint of taste in low-calorie soft drinks, saccharin was displaced out of this important market. Nevertheless, saccharin will for the foreseeable future continue to play an important role, since, apart from price, its chemical stability, in cooking for example, offers a decisive advantage.

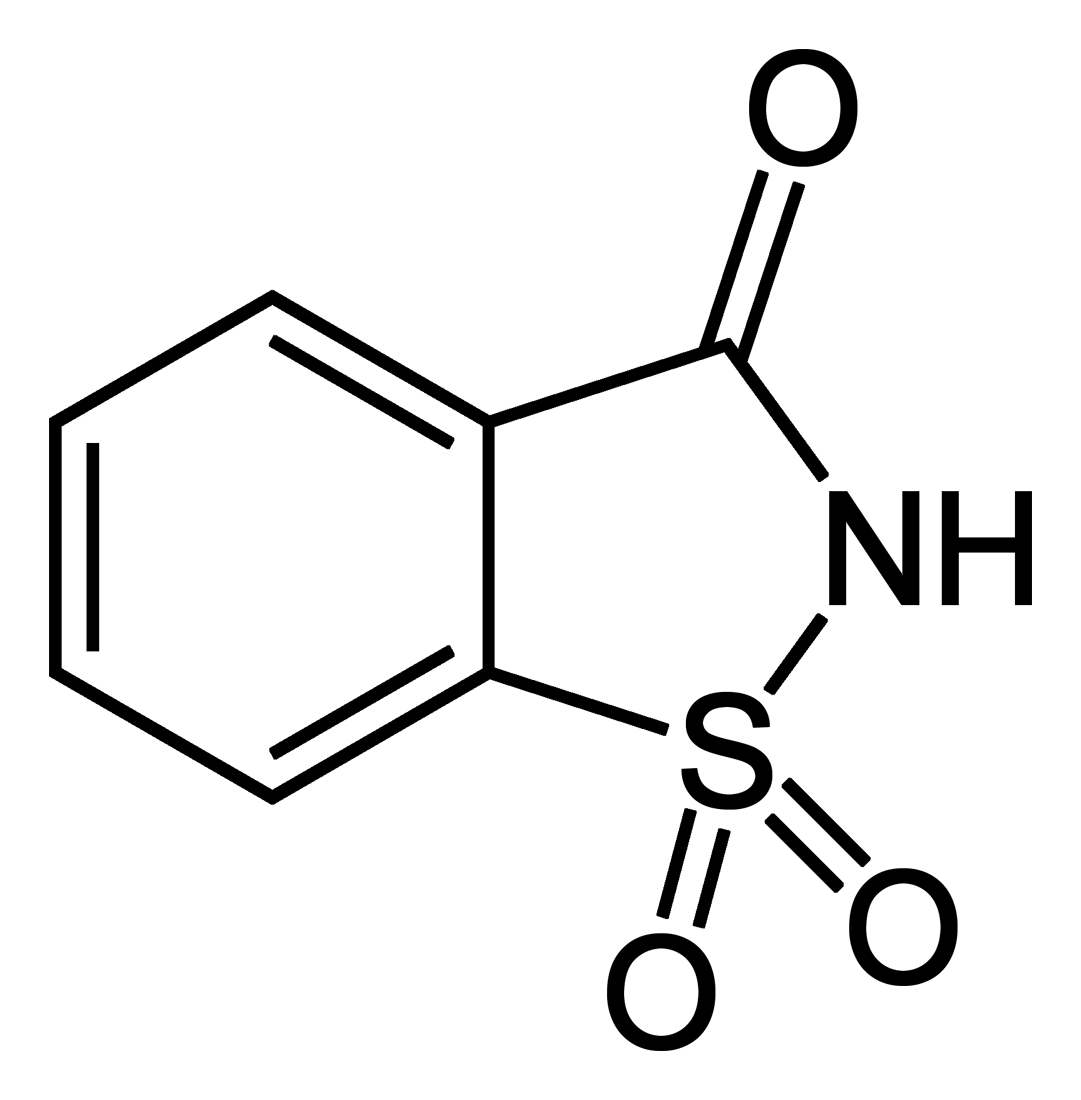

It is a time-honored maxim that from the biographies of interesting people we can experience and learn a great deal about ourselves and our constantly changing society. That a small molecule can also do so is shown by 1,1-dioxo-1,2-benzothiazol-3-one (saccharin’s official IUPAC name).

Other natural and artificial sweeteners that have already been approved, as well as possible future ones, will be discussed in subsequent sections of this article.

References

[22] World Health Organization, 30th World Health Assembly, Provisional Summary Record of the Seventh Meeting, 11 May 1977.

[23] P. M. Priebe, G. B. Kauffman, Minerva 1980, 18, 556. DOI: 10.1007/BF01096124

[24] O. P. Snyder, Auditierung zur Lebensmittelhygiene (Ed. N. Chesworth), Behr’s Verlag, Hamburg, 1999 (in German). ISBN: 978-3860224632

[25] Saccharin: A Chemical in Search of an Identity, Commentary in Science, 1977, 196, 1179. DOI: 10.1126/science.196.4295.1179

[26] C. de la Peña, Empty Pleasures, University of North Carolina Press, USA, 2010. ISBN: 9780807872741

[27] B. Armstrong, R. Doll, Brit. J. Prev. Soc. Med. 1975, 29, 73. Link

[28] U. P. Thorgeitsson et al., J. Nat. Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 19. DOI: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.19

[29] G. Kaufmann, Verlagsbeilage “journalist” 1979, Verlag Rommerskirchen (in German).

[30] International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS), INCHEM, Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives, Evaluation of Saccharin.

The article has been published in German as:

- Die Saccharin-Saga,

Klaus Roth, Erich Lück,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2011, 45, 406–423.

DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.201100574

and

- Kalorienfreie Süße aus Labor und Natur,

Klaus Roth, Erich Lück,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2012, 46, 168–192.

DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.201200587

and was translated by W. E. Russey.

The Saccharin Saga – Part 1

The invention of the first artificial sweetener and a lifetime battle for credit

The Saccharin Saga – Part 2

The early industrial production and organized smuggling of saccharin

The Saccharin Saga – Part 3

The health concerns associated with artificial sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 4

A glance back to ancient Rome, and the most hair-raising of all sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 5

What’s in your softdrink? – Introducing cyclamate

The Saccharin Saga – Part 6

Aspartame – a sweet dipeptide ester

The Saccharin Saga – Part 7

Acesulfame-K – another successful sweetening agent

The Saccharin Saga – Part 8

Thaumatin – a sweet protein with a licorice aftertaste

The Saccharin Saga – Part 9

Sucrose or Splenda turned into a low-calorie alternative to sucralose or saccharose

The Saccharin Saga – Part 10

Combining sweet cations and anions, and turning bitter compounds into sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 11

Intelligent synthetic strategies for low-calorie sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 12

Stevia plant extracts as low-calorie sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 13

Finding the best mixture of sweeteners to replicate the taste of real sugar

See all articles by Klaus Roth published in ChemistryViews Magazine