After looking at saccharin, the first artificial sweetener, and at the sweet, but poisonous lead(II) acetate used in ancient Rome, we turn to another sweet-tasting no-calorie compound that was discovered accidentally: cyclamate.

13. Cyclamate

More than fifty years after the chance discovery of saccharin (pictured right; see Part 1 to Part 3), sweet fortune elected to favor another chemist. This time it was a doctoral candidate, Michael Sveda (1912 – 1999), at the University of Illinois, Champaign, USA. In his thesis under Ludwig D. Audrieth (1907–1967) he intended to synthesize new antipyretic agents, when a cigarette he lit one day in the laboratory (yes, doing that used to be commonplace!) seemed to taste unusually sweet.

More than fifty years after the chance discovery of saccharin (pictured right; see Part 1 to Part 3), sweet fortune elected to favor another chemist. This time it was a doctoral candidate, Michael Sveda (1912 – 1999), at the University of Illinois, Champaign, USA. In his thesis under Ludwig D. Audrieth (1907–1967) he intended to synthesize new antipyretic agents, when a cigarette he lit one day in the laboratory (yes, doing that used to be commonplace!) seemed to taste unusually sweet.

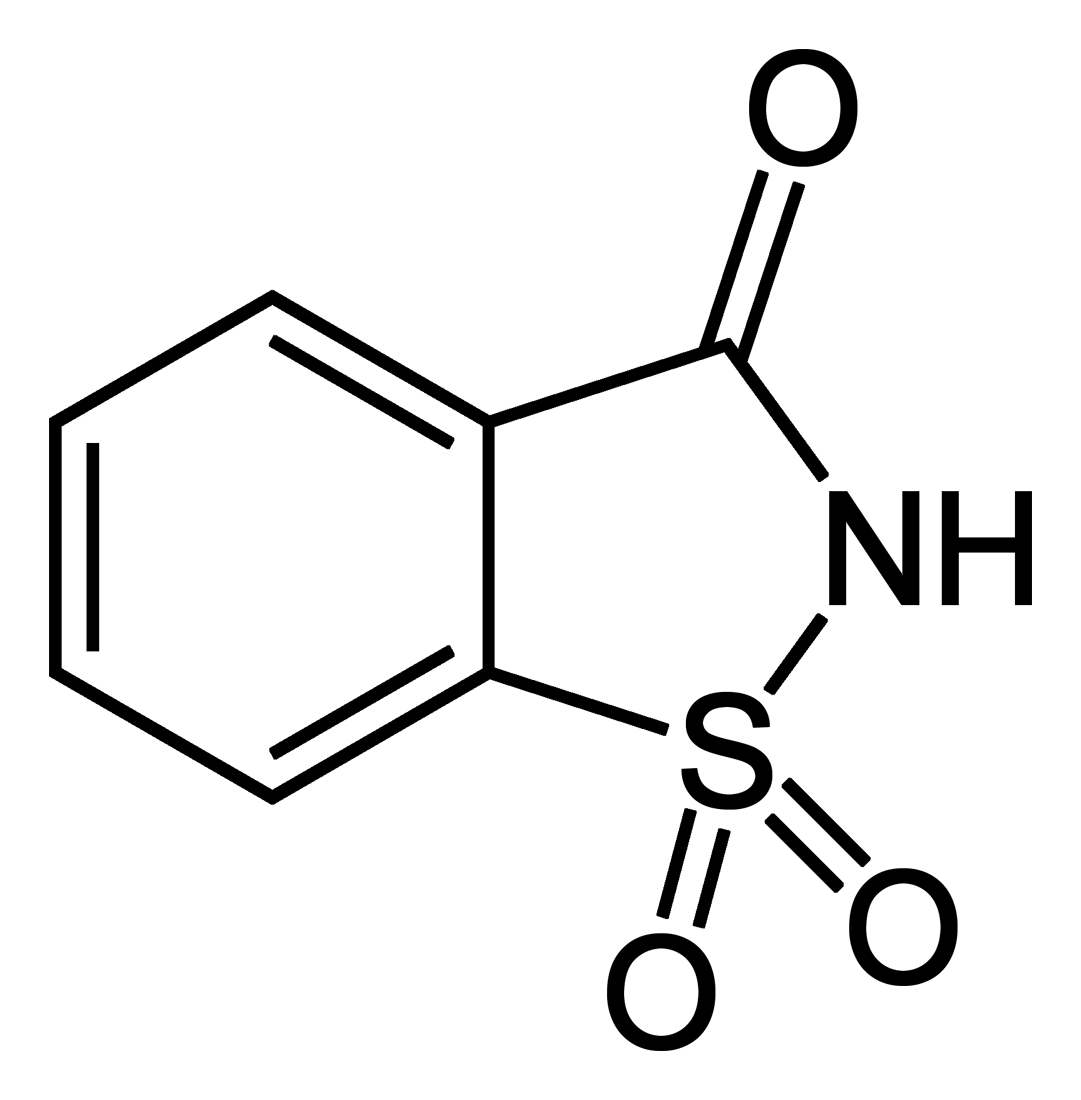

The cause was quickly discovered (Fig. 13): Cyclohexylsulfaminic acid (4a) [44], prepared by chlorosulfonation of cyclohexylamine (13), turned out to be an extremely sweet substance [45]. After Sveda moved on to E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Company (DuPont), acid 4a and its sodium, potassium and calcium salts (4b–d) were patented under the umbrella term “cyclamate”. This patent was subsequently assumed by Abbot Laboratories, USA, in the hope that cyclamate might be able to mask the unpleasant bitter taste of antibiotics, as well as of the sleep-inducing drug pentobarbital.

|

|

|

Figure 13. Synthesis of cyclamate (4b-d). |

Cyclamate could not compete directly as a sweetener with saccharin, however, given that the latter was ten times as sweet and less expensive to prepare. But cyclamate had one decisive advantage: the impression conveyed by its taste corresponded nearly to that of cane sugar, without the unpleasant metallic aftertaste of saccharin. It is thus no wonder that the first diet (sugar-free) soft drink marketed, a cola, was sweetened not with saccharin, but with cyclamate (see Fig. 14).

|

|

|

Figure 14. New York beverage manufacturer Hyman Hirsch initiated No-Cal, the first soft drink free of calories. |

No-Cal

In 1952, a well-to-do New York beverage manufacturer by the name of Hyman Hirsch (see Fig. 14, left) was elected honorary vice president of the Jewish Sanitarium and Hospital for Chronic Diseases of Brooklyn, NY, USA (renamed in 1954 the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital, and in 1968 the Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center). Hirsch hoped to make life a bit easier for the institution’s chronic diabetics and cardiac patients by providing them with a sugar- and calorie-free soft drink. Many recipes were tested involving the two artificial sweeteners available at that time (saccharin and the new cyclamate). Saccharin fell through the cracks in these tests due to its metallic aftertaste. Since cardiac patients would have needed a sodium-free beverage, the only reasonable possibility that remained was calcium cyclamate. This sweetener thus became the basis for “No-Cal”, the pioneering calorie-free soft drink first served in 1953 to patients in the hospital. Available flavors were “ginger” and “black cherry”.

“No-Cal” proved so popular from a taste standpoint that Hirsch Beverages Inc. of Flushing, NY, USA, began to market it also outside the sanitarium. It was a sensational success, especially thanks to an advertising campaign in which the focus was not on the health benefits of “No-Cal”, but rather on maintenance of a slim, feminine waist. Hollywood beauties such as Kim Novak and Jan Sterling proved convincing to female customers for “No-Cal” thanks to their (at the time) “ideal figures” (see Fig. 14). Within a single year, annual sales passed six million dollars.

Cyclamate/Saccharin Mixtures

The true significance of cyclamate came not through its use as a pure sweetener, but rather in mixtures. The optimum combination proved to be a 1:10 mixture of saccharin (S = 350) and cyclamate (S = 35), in which each component contributed the same level of sweetening, but the saccharin aftertaste was absent. The combination proved to be a worldwide success, displaying good stability to both heat and pH [45, 46]. Clearly the market for calorie-free soft drinks, especially colas, played a major role.

Given the astonishing success of “No-Cal”, the Royal Crown Co. of Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, brought the first calorie-free cola to market in 1958. “Diet Rite Cola” was also sweetened with a cyclamate/saccharin mixture, and was initially promoted strictly as a dietetic beverage. In 1962 the advertising strategy was altered, however. Now, the focus was not a slender body, but rather the flavor of Diet Rite, together with a positive attitude toward life. As the “Feel All Right” drink, Diet Rite quickly conquered the American market, since men – who were less concerned with their figures – could also be won over. Indeed, calorie-free Diet Rite assumed fourth place among all soft drinks in the United States, surpassed only by the major sugar-containing colas.

Sales of “no-calorie soft drinks” for the first time exceeded $18 million when the giants Coca-Cola and Pepsi finally awoke and followed suit, albeit hesitantly at first. Both companies were anxious and avoided any name similarity between the new “diet product” and their traditional version, presumably so that potential failure of the new diet drink would not harm the classical trade name [46a]. Thus, Coca-Cola in 1963 introduced “Tab”, while Pepsi went initially with “Patio Diet Cola” (renamed “Diet Pepsi” in 1964). All the low-calorie colas in those days were sweetened with cyclamate/saccharin (10/1).

Cyclamate Metabolism

Both saccharin and cyclamate are eliminated by mammals unchanged, by way of the kidneys and the bladder. This and all the scientific studies to date had caused the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1958 to classify both sweeteners as “GRAS” (Generally Recognized as Safe), which is to say utterly harmless. This assessment was confirmed by the FDA in 1967. Nevertheless, one indication had appeared that intestinal bacteria could decompose cyclamate (4a–d) into cyclohexylamine (13), which as a primary amine had carcinogenic potential. The compound can react with nitrites in the body and be converted into the carcinogenic N-nitroso-cyclohexylamine. A long-term study initiated in 1967 and conducted by an independent research institute (though financed by the manufacturer, Abbott Laboratories) thus took on special significance [47]:

60 rats were fed 2.5 g/kg of cyclamate daily, either alone or in a saccharin/cyclamate mixture (1:10). At this heavy dose, almost all the animals eliminated more than 0.1 % of the dietary cyclamate as cyclohexylamine via the bladder. After a year, all the animals were still healthy. After 78 weeks, 50 animals were still alive, compared with 55 animals from a control group of 60. After 104 weeks (= 2 years), 34 animals (control group 39) were still alive, and at the end of the experiment, bladder tumors had formed in 8 of 60 rats. After 79 weeks, some of the animals had been supplied with an additional 125 mg/kg of cyclohexylamine. Surprisingly, this had no significant effect on the development of bladder tumors.

The FDA pointed out that there was no indication whatsoever that the sweetener mix would prove carcinogenic with humans, but because of the Delaney Clause (see The Saccharin Saga – Part 3), the GRAS status for cyclamate would have to be lifted, and a ban on its use recommended. A high point was appearance of the FDA scientist Jaqueline Verrett on the primetime NBC Evening News. She chose in particular to show pictures of crippled chicks that had been hatched from eggs into which cyclamate solution had previously been injected. With her assertion “More dangerous than Thalidomide”, the American public became permanently convinced that cyclamate was a work of the devil [48–50].

Thalidomide was the active ingredient in the sleep aid Contergan, at one time freely dispensed over the counter. In the period 1959–1962, it resulted in a terrible drug disaster, causing tens of thousands of newborns (especially in Europe) to be malformed. The president of the American Council on Science and Health pointed out, however, that similar chick malformations were also observed from hen’s eggs into which a salt solution or air had been injected.

In October 1969, cyclamate was banned in the United States, but oddly enough classified for the first time in Great Britain and other European countries as a permitted, harmless sweetener.

How is it that health authorities in different countries can, on the same scientific basis, come to contrary conclusions?

Here it’s worth our pausing to look a bit more closely. First, one must remember that, in the crucial study the amount of sweetener supplied to the rats was exorbitantly high, and if extrapolated to humans would correspond to lifelong daily consumption of 330 cans of cola containing sweetener.

Reactions were appropriately sarcastic. An op-ed in the leading British medical journal The Lancet scoffed: “Never have so many pathologists been assembled to offer their judgment over such trivial tissue changes in such a humble species as the laboratory rat”; and an op-ed in Nature noted that the evidence against cyclamate was “as sustainable as cotton candy”. Indeed, numerous American scientific institutions like the National Academy of Sciences and the Cancer Assessment Committee of the FDA determined that cyclamate was not a carcinogen, and criticized the careless practice of the regulators.

None of the studies carried out in subsequent years on rats, mice, dogs, hamsters, or monkeys revealed any carcinogenic effects of cyclamate. For this reason, Abbott petitioned for the lifting of the cyclamate ban in 1973. The request was denied in 1980, however, and Abbott submitted a second petition in 1982. In the meantime, the National Academy of Sciences declared that none of the animal studies, neither with cyclamate nor its metabolites, had provided any suspicion of carcinogenicity. Since the middle of the 1980s the FDA itself had also taken this point of view. However, cyclamate is still banned in the United States. For over 30 years the 1982 petition has no longer been challenged [51]. Were the FDA at some point to again categorize cyclamate as GRAS, it is uncertain whether a potential American market for the substance would still exist, given the ban of more than 40 years and various alternative sweeteners that have in the meantime been developed.

After the first announcement of a cyclamate prohibition in October 1969, beverage manufacturers in the United States were forced almost overnight to remove certain products from the shelves and replace them with ones based on new formulations. Only saccharin remained as a permitted artificial sweetener, with its bitter-metallic aftertaste. This was something consumers either had to put up with, as with Coca-Cola’s “Fresca”, a carbonated diet beverage with a grapefruit/lemon flavor, or else the aftertaste was masked by addition of a little sugar, as in the case of Coca-Cola’s “Tab”. The latter approach was preferred also by other cola manufacturers, resulting in sudden transformation of “calorie-free” into “low-calorie” colas (see Fig. 15).

|

|

|

Figure 15. The United States cyclamate ban of 1969. |

Now It Was Saccharin’s Turn!

New sweetener troubles started a few years later. This time it was saccharin’s turn, and another dubious rat study was the origin, presenting the Americans with a déjà-vu experience (see The Saccharin Saga – Part 3). In a Canadian investigation completed in 1977, rats were fed with saccharin over the course of two generations at a saccharin level of 2.5 g/kg daily. In the first generation, three of 100 rats developed bladder tumors, and in a second generation, the number was 14 of 100. The dosage, incidentally, corresponded to a human intake per day of 800 cans of saccharin-sweetened soft drink, or else more than 6000 saccharin tablets – and that every day for a lifetime. Once again, political activism triumphed over sound judgment and reason: the Canadian Minister of Health, Marc Lalonde, decided upon an immediate nation-wide ban on saccharin.

The new Canadian saccharin prohibition created a predicament for the US FDA, since the decision could not simply be ignored. Strict adherence to the terms of the Delaney Clause threatened to result in a saccharin ban in the United States, too, meaning there might now be absolutely no US availability of any artificial sweetener whatsoever!

Given this dismal prospect, at least parts of the American national spirit began to seethe. Gaining moral support from the American Cancer Society and the American Diabetic Association, much of the general populace saw this threat of a possible total ban as completely unreasonable. The newly-elected President, Jimmy Carter, and every member of Congress, found themselves overwhelmed with protest letters, with women in particular constituting an especially vociferous protest body.

This strident force sent politicians to their knees, whereupon some of them became remarkably creative. Thus, Congress now slipped through a shrewd legal loophole, authorizing a moratorium rather than an outright ban. In this way, a decision regarding an actual saccharin prohibition could be deferred, permitting further animal studies to supposedly be conducted. In the meantime, all saccharin-containing products would be required to carry a warning notice (see Fig. 16) about possible carcinogenic concerns. This moratorium was repeatedly extended, year after year, until in 2001 the saccharin ban – warning notice and all – was (in complete silence) simply laid to rest.

|

|

|

Figure 16. Diet Rite Cola without (left) and with (right) its warning regarding saccharin, obligatory in the United States since 1978. |

Summary

The sweetener duo saccharin/cyclamate is still utilized today in table sweeteners, either in the form of tiny cubes or as a solution, so it may be helpful to summarize the confusing historical back and forth: Two dubious studies with rats, quickly shown not to be reproducible, led on purely political grounds to overly hasty and scientifically unwarranted bans in the United States and Canada, causing both saccharin and cyclamate to fall into disrepute.

For years, neither compound has been seriously suspected of posing any health risk to humans when consumed at realistic levels. This point of view has been adopted by scientific institutions and health authorities throughout the world, with the result that both substances are now appropriately permitted virtually everywhere. No one understands why saccharin remains banned exclusively in Canada and cyclamate in the United States, probably including the respective health authorities themselves.

References

[44] L. F. Audrieth and M. Sveda, J. Org. Chem. 1944, 9, 89. DOI: 10.1021/jo01183a011

[45] D. J. Ager et al., Angew. Chem. 1998, 110, 1900. (in German) DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3757(19980703)110:13/14<1900::AID-ANGE1900>3.0.CO;2-R

[46] K. O. Paulus and M. Braun, Ernährungs-Umschau, 1988, 35, 384. (in German)

[46a] B. Siegel, American Heritage 2006, 57. Link

[47] J. M. Price et al., Science, 1970, 167, 1131. DOI: 10.1126/science.167.3921.1131

[48] J. Schwarcz, The Gazette (Montreal) 2007, February 16.

[49] E. M. Whelan, Wall Street Journal 1999, August 26.

[50] K. Roth, Chem. Unserer Zeit, 2005, 39, 212. (in German) DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.200590038

[51] Cyclamate, Commissioner’s Decision, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). www.fda.gov

The article has been published in German as:

- Die Saccharin-Saga,

Klaus Roth, Erich Lück,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2011, 45, 406–423.

DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.201100574

and

- Kalorienfreie Süße aus Labor und Natur,

Klaus Roth, Erich Lück,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2012, 46, 168–192.

DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.201200587

and was translated by W. E. Russey.

The Saccharin Saga – Part 1

The invention of the first artificial sweetener and a lifetime battle for credit

The Saccharin Saga – Part 2

The early industrial production and organized smuggling of saccharin

The Saccharin Saga – Part 3

The health concerns associated with artificial sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 4

A glance back to ancient Rome, and the most hair-raising of all sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 5

What’s in your softdrink? – Introducing cyclamate

The Saccharin Saga – Part 6

Aspartame – a sweet dipeptide ester

The Saccharin Saga – Part 7

Acesulfame-K – another successful sweetening agent

The Saccharin Saga – Part 8

Thaumatin – a sweet protein with a licorice aftertaste

The Saccharin Saga – Part 9

Sucrose or Splenda turned into a low-calorie alternative to sucralose or saccharose

The Saccharin Saga – Part 10

Combining sweet cations and anions, and turning bitter compounds into sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 11

Intelligent synthetic strategies for low-calorie sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 12

Stevia plant extracts as low-calorie sweeteners

The Saccharin Saga – Part 13

Finding the best mixture of sweeteners to replicate the taste of real sugar

See all articles by Klaus Roth published in ChemistryViews Magazine

.jpg)