A growing collection of articles highlights how chemistry is increasingly essential in crime scene investigations (CSI) and solving crimes

The Director of the Forensic Police Service in Rome discusses the challenges of forensic work, adapting to new techniques, and the TV portrayal of investigations

The Perfect Crime

A devilish plan – thwarted by general chemistry knowledge

Looking Over the Shoulders of Pathologists

Focus: When Corpses Meet Forensic Pathologists,

A look behind the scenes at two cases that illustrate the different approaches used in forensic toxicology

A Historical Crime Story

Focus: Our Daily Bread,

Transformation of ripe ears of grain into a fragrant, aromatic bread borders on the miraculous and behind such a miracle lies chemistry

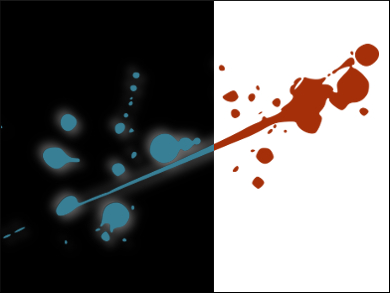

Criminal Investigation—Blood Traces

Finding small blood traces at crime scenes is crucial in forensic science. Luminol, activated by hydrogen peroxide and sodium hydroxide, reacts with the iron in hemoglobin to make it glow blue. Dried and decomposed blood give a stronger and more lasting reaction than fresh blood.

The blue glow lasts for about 30 seconds and detecting the glow requires a quite dark room. Luminol also reacts with other substances like copper, bleach, and fecal matter, potentially causing false positives, and luminol can interfere with other tests.

Malaria drug finds second use in selective bloodstain visualization

Raman spectroscopy allows accurate dating of up to two year old bloodstains

Simple and effective visualization method uses polymer solution-soaked cotton pads

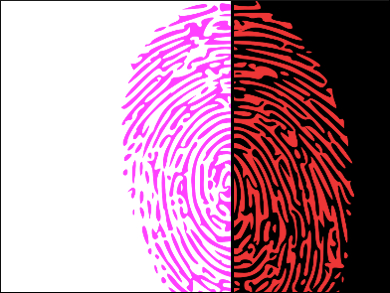

Criminal Investigation—Fingerprints [1]

Fingerprints are unique, durable, and difficult to alter. When a finger touches a surface, sweat and oily substances like sebum usually leave an invisible print called a latent fingerprint. Latent fingerprints are impressions left by the friction lines of human fingers.

Patent prints are visible fingerprints left in substances such as blood, ink or dirt, while plastic prints are visible impressions left in flexible materials such as clay or wax. Both types can usually be captured by photography, although techniques are sometimes used to enhance their clarity.

Detecting latent fingerprints may require chemical techniques such as powder dusting, ninhydrin spraying, iodine fuming, or silver nitrate treatment, depending on the surface. While hundreds of detection methods exist, many are of limited practical use.

Powders, typically consisting of a pigment (which provides contrast) and a binder (which helps the powder adhere to the print), are carefully brushed onto the surface to adhere to the moisture and oil left by the finger. Commonly used pigments include colloidal carbon particles or metal flakes such as aluminum, zinc, and copper. Fluorescent powders, which fluoresce in the presence of certain colors of light, are increasingly being used along with lamps with various alternative light sources. Common binders include gum arabic, iron powder, and colophony.

Another possibility is to use cyanoacrylates that polymerize on contact with the residue of the fingerprints and thus follow the line of the ridges. This is often used on rough surfaces.

Chemical developers such as ninhydrin react with amino acids in sweat or skin when sprayed on the surface to produce a purple compound called Ruhemann’s purple after Siegfried Ruhemann who discovered it in 1910. This method is also used on rough surfaces such as paper. Ruhemann’s purple breaks down in the presence of light and oxygen, and the reaction requires moisture. There are other compounds that also fluoresce, such as 1,8-diazafluoren-9-one (DFO).

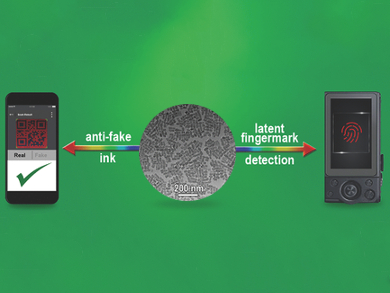

Lanthanum vanadate nanoparticles can be used in anti-forgery ink and fingerprint detection

Progress in fingerprint analysis means fingerprints can show whether a suspect is a smoker, takes drugs, or has handled explosives

Functionalized polymer dots as fluorescent and colorimetric probes

Criminal Investigation—Listick

Improved method for lifting lipstick samples from crime scenes and analyzing them in the lab

DNA Evidence

The introduction of DNA analysis in the mid-1980s transformed forensic science, allowing even tiny amounts of biological material to link suspects to crimes or develop clues. Its increasing accuracy has also made it a critical tool for freeing wrongfully convicted.

Reference

[1] A Simplified Guide To Fingerprint Analysis, website of the National Forensic Science Technology Center (NFSTC), now the Global Forensic and Justice Center (GFJC) 2013. (accessed September 13, 2023)