Hijacking Chemical Communication

For much of life on earth, chemical communication is important. Volatile organic substances that act as sex pheromones in moths, for instance, draw the male to the female who biosynthesizes. Eau de toilette and perfume are synthesized on an industrial scale by humans for pretty much the same purpose.

Where there is communication, there is the potential for obfuscation, masked signals, encrypted messages, and even the hijacking of the systems by third parties. The latter was the evolutionary result for a rare species of plant known as Drakaea micrantha, the dwarf hammer orchid.

Pollinator Impostor Syndrome

This south-west Australian species of hammer orchid, like many other species of its ilk, has evolved to be pollinated by a single species, male Zeleboria thynnine wasps. This makes the plant’s sexual reproduction vulnerable to the comings and goings of this one pollen carrier. The orchid has become very adept at deceiving the male wasps.

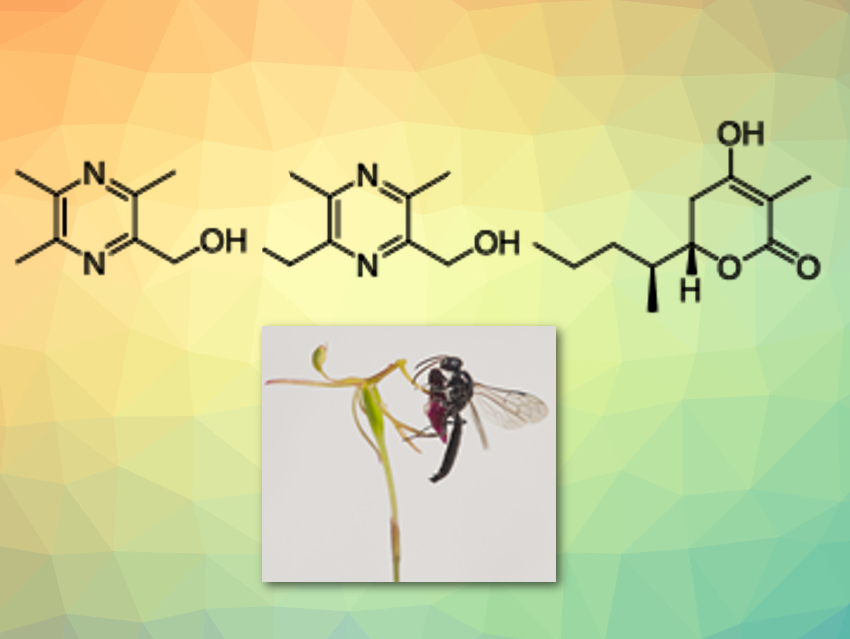

The most obvious way in which the orchid hijacks the mating behavior of the wasps is that its labellum, one of its petals, has a very similar shape to the flightless female thynnine wasp (pictured). The plant also has a silvery-grey, heart-shaped leaf with prominent green veins and a stem up to 300 millimeters long, which one might whimsically suggest acts as a landing strip for the males drawn to the sight of the fake female.

An Accent on Scent

However, visual cues are not necessarily going to draw the waspish crowds, who will carry away the orchid’s pollen to the next pretend tryst and so complete the plant’s life cycle by bringing together pollen and egg cells. This brings us back to chemical communication: The dwarf hammer orchid has evolved the necessary biosynthetic systems to generate a heady brew of a β-hydroxylactone and two specific hydroxymethylpyrazines.

This combination mimics the sex pheromone of the thynnine wasp in a potent way. Carried on the Australian breeze through the bare sand, woodland habitats of the orchid, it draws the males almost as effectively as the female wasp herself.

Björn Bohman, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, and Australian National University, Canberra, and colleagues have discovered this special combination of chemicals. They point out just how unique it is that a plant exploits a mixture in this way rather than having evolved a single compound as a pheromone mimic.

Moreover, given that this rare species is considered an endangered plant, the findings could be used to artificially boost the chances of attracting the species’ pollinators and, thus, allow humans to intervene and assist with its reproduction. The team has made available a synthetic blend that could be used by orchid specialists and entomologists to home in on likely sites in the region where the wasp is plentiful and the plant might thrive.

A Winning Combination

The researchers point out that there are hundreds of species known to use sexual deception to attract males of an insect species into their pollen-producing regions. This trickery is particularly common in orchid species and often, it is incredibly specialized—as with the dwarf hammer orchid and the thynnine wasp.

Generally, little is known about the specific chemicals involved. Some research has revealed orchids that use an alkane or alkene, some that exploit a hydroxy- or keto-acids, and there is an example of cyclohexane-1,3-diones being used by Chiloglottis orchids. Hydroxymethylpyrazines have been noted in Drakaea species, (methylthio)phenols in Caladenia, and tetrahydrofuranyl acids in Cryptostylis. The team explains that when a mixture of compounds is used, it is usually a group derived from similar biosynthetic origins rather than disparate compounds.

The researchers used gas chromatography-electroantennography (GC-EAD), where actual insect antennae from the wasp acted as the detector to work out what Drakaea micrantha, the smallest of this family or orchids, was using to attract its pollinator. Specifically, the team identified a formula containing 2-hydroxymethyl-3,5,6-trimethylpyrazine (pictured left), 2-hydroxymethyl-3,5-dimethyl-6-ethylpyrazine (pictured center), and a unique β-hydroxylactone, 4-hydroxy-3-ethyl-6S-(pentan-2S-yl)-5,6-dihydro-2H-pyran-2-one, which the team called drakolide for the sake of simplicity.

“This work couldn’t have been done without solid collaborations between biologists, analytical chemists, and synthetic chemists, because field bioassay methods, advanced chiral-phase chromatography, synthesis, and crystallography were all required to solve the problem,” Bohman told ChemViews Magazine. He adds that the team is already extending the research to test the hypothesis that drakolides are widely used by both thynnine wasps and the orchids that exploit them. “We are hoping to extend this kind of investigation to other endangered orchids that are dependent on specialized pollinators,” he explains, “and we’re planning and hoping to investigate drakolide biosynthesis.”

- A specific blend of drakolide and hydroxymethylpyrazines – an unusual pollinator sexual attractant used by the endangered orchid Drakaea micrantha,

Björn Bohman, Monica Tan, Ryan Phillips, Adrian Scaffidi, Alexandre Sobolev, Stephen Moggach, Gavin Flematti, Rod Peakall,

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019.

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201911636