With the EU Green Deal, Europe wants to become a leader in sustainable chemistry. The German government’s proposal for climate neutrality by 2045 represents an epoch-making challenge for the chemical and pharmaceutical industry, even though the sector has already reduced its emissions by more than half since 1990.

However, they want to achieve greenhouse gas neutrality—and they also believe that they are capable of doing so. However, it will demand an innovative, forward-looking approach. To take a pioneering role in achieving this ambitious goal, the German Chemical Industry Association (Verband der Chemischen Industrie e.V., VCI) and the Association of German Engineers (Verein Deutscher Ingenieure, VDI) have launched the “Chemistry4Climate” platform [1]. Through this platform, and together with a broad-based group of experts from various sectors and ministries as well as societal representatives, they want to discuss proposals and develop concrete solutions that are supported by a broad consensus to achieve net-zero carbon emissions of German chemical production by 2050.

Jenna Juliane Schulte, who is responsible for the project Chemistry4Climate at the VCI, and Manfred Ritz, head of the VCI’s media and editorial department, talk with Vera Koester for ChemistryViews about the goals of the platform and the biggest challenges in the transition process, especially those facing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

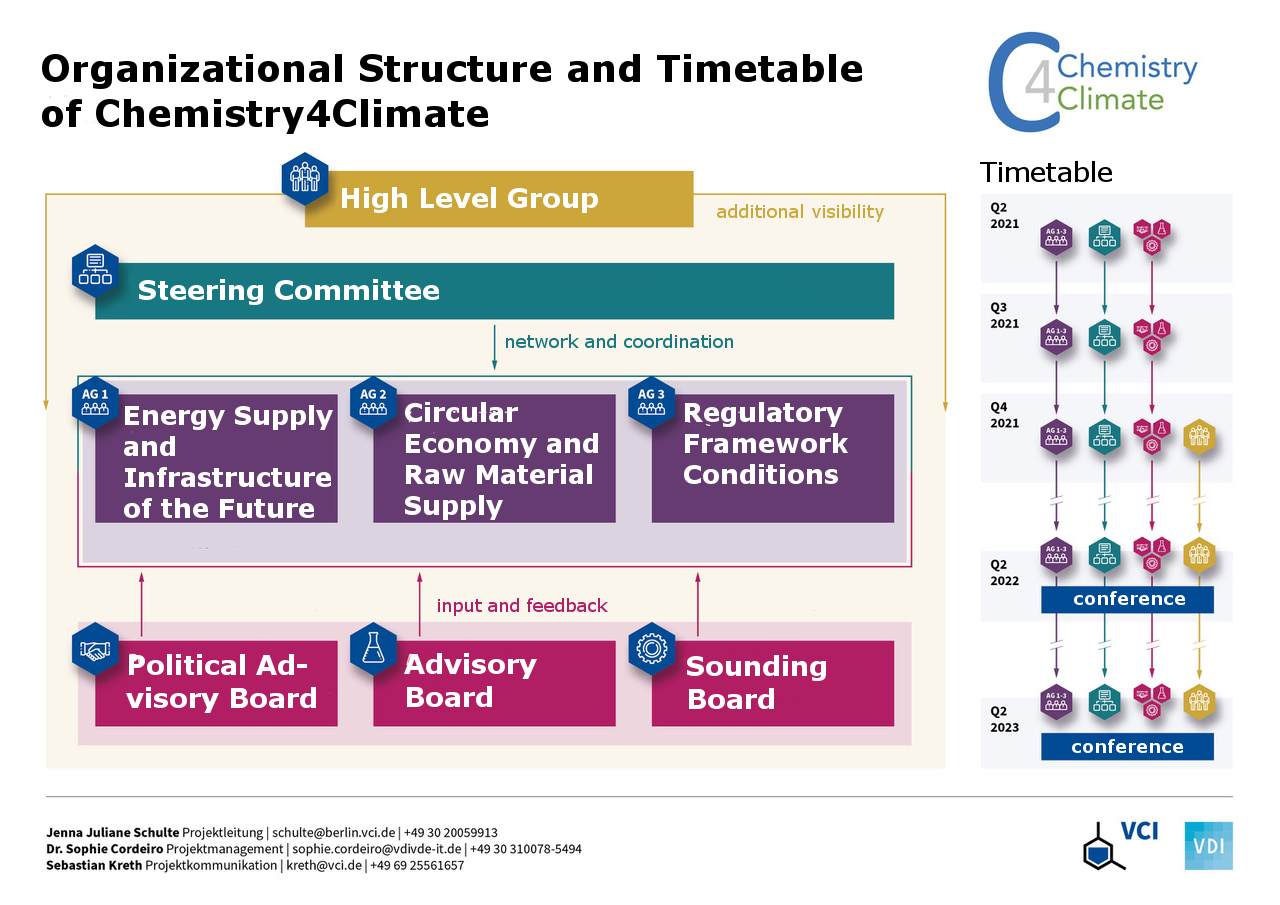

Organizational structure and timetable of Chemistry4Climate.

How did the idea of the Chemistry4Climate platform come about?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: The background is our study from 2019 [2], our Roadmap 2050, in which we described that the chemical industry can produce in a greenhouse-gas-neutral way by 2050. Technologically, this is possible, but only under very specific conditions. For example, we need the massive capacity of 628 terawatt-hours of renewable electricity and at a competitive price of 4 cents per watt.

The aim of the platform is for us to look very closely at how we can actually achieve these framework conditions, what concrete concepts we need for this, and how we can make the whole thing a reality.

In the process, the chemical industry simply reaches its natural limits; we cannot and we do not want to plan this on our own. For example, the topic of infrastructure expansion is super central to the energy transition—so that, say, the renewable electricity from the North Sea is also available to southern Germany. To do that, certain infrastructure has to be expanded, and that’s not something the chemical industry does. We also normally do not build renewable-energy plants.

That is why we came up with the idea of bringing together many different stakeholders, each of whom can contribute their expertise.

How is the platform structured?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: The platform is not just a website where you can exchange ideas. It is a stakeholder dialogue platform for developing concrete concepts together. In other words, at the heart of this platform are three working groups: one on the topic of energy supply and infrastructure of the future (also known internally as WG1), one on the circular economy and raw material supply of the future (WG2), and a third on regulatory framework conditions (WG3). In this last working group, we will put the current regulations to the test and also want to talk about new policy instruments to accompany new technologies.

Jenna Juliane Schulte: The platform is not just a website where you can exchange ideas. It is a stakeholder dialogue platform for developing concrete concepts together. In other words, at the heart of this platform are three working groups: one on the topic of energy supply and infrastructure of the future (also known internally as WG1), one on the circular economy and raw material supply of the future (WG2), and a third on regulatory framework conditions (WG3). In this last working group, we will put the current regulations to the test and also want to talk about new policy instruments to accompany new technologies.

These three working groups are supported by various advisory boards and committees. For example, there is a political advisory board that consists of members of the European Parliament and the German Bundestag. There is also a scientific advisory board as well as one from the industry associations.

Then we have a steering committee that keeps the working groups together and coordinates them so that they do not work against each other or on the same topics, and a high-level group with members from the executive committee of the VCI, the president of the VDI (Association of German Engineers), the president of the NGO Germanwatch, and the president of the IG Bergbau, Chemie, Energie (Mining, Chemical and Energy Industrial Union; IG BCE)—in other words, a very high-ranking group.

Chemistry4Climate has just started. What has already happened and what is happening next?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: The project is designed to span two years. We started in May 2021, and we want to have completed the project by the end of April 2023. Along the way, as I said, we want to develop very specific concepts on individual topics and publish papers on them that we can give to political decision-makers.

However, two studies are also planned at the very beginning in WG1 and WG2, where we first want to gather all the facts and lay the groundwork so that all stakeholders are on the same page. The idea is that we do not have to say, this is our roadmap, take it or leave it, but that we all have a common definition of the problem.

We will also organize a conference and, of course, conclude the whole thing with a big conference. If necessary, we will also do a large final study.

The goal at the end should then be a proposal where the politicians are given advice, in a manner of speaking, or to suggest to them that we need this or that, otherwise we will not be able to achieve greenhouse-gas neutrality?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: Well, we have several goals. The goal is not only to reach the end of the platform, but over the course of the platform, we want to develop initial recommendations for action. Of course, these are aimed at the political decision-makers, that is, from both the German Bundestag and the EU Parliament, and certainly also the ministries. We plan to publish something regularly along the way until the end of April 2023.

And, of course, our goal is also to have a new technology path at the end, so to speak, with technologies related to the circular economy as well as technologies related to energy supply, which will answer associated questions such as when which infrastructure must be developed for hydrogen, for natural gas, for electricity, and which regulatory framework conditions and which policy instruments we need for this. We want to have a coherent picture from all the results for the path to 2050.

At the same time, however, one of the platform’s goals is to bring together players who have perhaps not yet spoken to each other, or at least not in this institutionalized form, and to create synergistic effects. For example, on the topic of circular economy, when different companies from the value chain talk to each other and the upstream entrepreneur sees what the entrepreneur in the downstream value chain actually requires, those synergistic effects can be achieved and perhaps projects can be identified that can be tested in real laboratories or other research projects on a different scale.

So we are not only working on concepts but are also trying to put them into practice. It is a very desirable goal that innovations are created; but this is, of course, also something that we cannot control in the end. We would like to initiate this and provide the platform for it.

BASF and RWE have just announced cooperation to build a wind farm together [3]. Is that something that the platform would promote or could come out of it?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: Yes, exactly. The big players like BASF and RWE are, of course, already talking to each other outside of the platform, as you can see, and that is a good thing. It is much more difficult for small and medium-sized enterprises, which are very numerous in Germany. But certainly, projects of this kind (i.e., cooperation between companies) are something we imagined would be encouraged.

How is the platform integrated into Europe? Are there connections to other countries or the EU?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: There are no similar platforms in other European countries. Initially, we had considered situating the project at the European level, but developing these concepts within a two-year period is already a very large, ambitious project for the German level alone. When you work on the European level, it becomes even more complex. That is why we decided to focus on the German level this time around.

Of course, that does not mean that we are not taking into account everything that is happening in Europe. In WG3, Regulatory Framework Conditions, we are dealing with the Green Deal and the EU’s fit-for-55 package at the very beginning. The EU level is where the framework conditions will ultimately be set. Germany then has to implement it and operate within the framework set by the EU. In this respect, this is, of course, a very important and influential factor in our discussions. We also have EU MEPs on the political advisory board who also give their feedback and input.

What about the participants in this platform? Is it a closed group? What requirements do you have to meet to be part of it?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: The working groups must be capable of performing their duties, which is why we have limited them to a maximum of 30 participants. That does not mean that we cannot or do not want to include other stakeholders as the process progresses. It can always happen that we notice that we are still lacking expertise in one area or another, and then we would ask specifically for it, or we would get in touch with people who can contribute a particular area of expertise that we have not yet covered. Then we would be happy to take them on board.

What motivates you personally to work on the Chemistry4Climate project?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: I think it is a super exciting project. Decarbonization is a must. And the Climate Protection Act has now been tightened up again: The deadline is no longer 2050 but 2045, and the chemical industry naturally has a major contribution to make. This is because, on the one hand, it is, of course, a major emitter; but on the other hand also because the products that the chemical industry manufactures contribute to climate protection, for example, through insulation or lightweight design, and in this respect, I think it is incredibly good. I thought it was good that we made the roadmap and said very progressively that we can become greenhouse-gas neutral by 2050. The fact that we are now taking this second step and really thinking about how we can achieve this is something that I find incredibly important and exciting about this project. That is why I am very happy to be doing this.

What do you think is the biggest challenge?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: I think every working group has its own biggest challenge. First, getting all the heterogeneous stakeholders to agree on a common denominator. And then you have to find the right concepts that will work in the long term.

Manfred Ritz: I was also at the annual Handelsblatt Energy Summit on the hydrogen economy for a while today. It is interesting to note that the industry is very concerned about how to achieve all this. They see the targets from politics and, basically, everyone knows how important hydrogen is, for example, for the chemical and the steel industries. But how the whole thing is to be set up, where the alternative energy capacities are to come from, all that naturally concerns them enormously.

I have been with the VCI for 34 years now and have rarely experienced a phase in which there is so much uncertainty for companies about what their future will look like in this changed system. This is an enormous upheaval that is having a major impact on the entire industry, and especially on small and medium-sized enterprises. The large companies, as you can see with BASF, are looking for solutions and preparing solutions. Of course, they have completely different preconditions in terms of capital, connections, employees, and know-how. But how are our 1,700 or 1,900 SMEs supposed to do that? That is a problem.

Where do you think is the biggest problem here?

Manfred Ritz: There are no clear structures of measures that companies can use to determine how they should implement this. What steps will politicians, whether in Germany or Europe, take for companies that want to use hydrogen? That has a big impact on costs. How will the companies be able to maintain the economic viability of their plants?

Of course, BASF has a completely different energy requirement, and they are now getting a dedicated line from RWE, so to speak. BASF is doing the same in China. But the medium-sized companies that are dependent on the general power supply are very worried about how they are going to manage it all. They are all ready, but the cost is a big point of concern.

That is why we at the VCI are stressing that in the next legislative period, policymakers must lower the cost of electricity prices for industry in Germany. Otherwise, nothing will work.

And are you seeing that politicians at least recognize the problem?

Manfred Ritz: I think so. There is a whole series of announcements from different parties. I think everyone is aware of the problem, and we have continuously emphasized it.

Can we learn from the Nordic countries, which are partly ahead of Germany in their use of green energy?

Manfred Ritz: I think the whole infrastructure of power generation is different. Today there was an announcement from the Federal Ministry of Economics that the NordLink line has now been completed so that essentially hydroelectric green power can be transported to Germany.

[NordLink is an electricity highway project by the Norwegian company Statnett and the German DC Nordseekabel GmbH & Co. KG. The line passes through the North Sea and connects the power grids of Norway and Germany].

This is an important step. But, of course, because we have industrial sites all over the country, we need the north–south connection for the power grids. Things still look very bleak there at the moment. Today, at the Handelsblatt Energy Summit, everyone repeated that one crucial point is that Germany now needs an enormous acceleration in the expansion of renewable energies.

Above all, of course, there is the problem of financing, which is another issue, but a way must be found. At the moment, the goals are all clear, functional quotas or years and intermediate stages; but the way to get there, that is still pretty much in the fog. Chemistry4Climate is an attempt to help clear this fog a bit.

Is this lack of definition over how the targets are to be achieved also responsible for the fact that we have not achieved the climate targets so far?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: It has also been allowed to run its course for a long time. Politicians may have had the impression for a long time that it would somehow work out and that the industry would somehow manage it. But somehow is definitely not enough. The problem is too huge for that.

Our chairman of the Energy and Climate Committee said at the Handelsblatt conference, “Compared to building up the use of green hydrogen in industry, converting the energy industry is child’s play.” The grids exist; it is about things that are relatively easy to do. In comparison, installing and building the hydrogen economy is a completely different issue.

So it remains exciting.

Jenna Juliane Schulte: Yes, we are also excited. The first meetings have now taken place and I have to say that there were definitely good discussions despite the fact that it was the first meeting and people were still getting to know each other. Everyone has contributed well and has already come up with good ideas. That was very enriching.

So when is the first milestone planned?

Jenna Juliane Schulte: A major milestone is planned for November/December of this year when the results of the first fact-finding studies from WG1 and WG2 will be available. WG1 is making an estimate for an overall balance—in other words, how much renewable energy can we produce, how much hydrogen do we need over time in which region, and what infrastructure do we need for this?

WG2 then estimates the potential for secondary raw materials, that is, how much biomass and how much waste are available to the chemical industry as a raw material over time. This will then form the basis for further discussion.

Thank you for the interview.

Reference

- Chemistry4Climate Platform

- Study Roadmap 2050: Auf dem Weg zu einer treibhausgasneutralen chemischen Industrie in Deutschland, VCI, Frankfurt, Germany 2019. (in German)

- BASF and RWE Cooperate on New Technologies for Climate Protection, ChemistryViews May 26, 2021.

Jenna Juliane Schulte graduated with a degree in European Studies from the University of Osnabrück, Germany. She worked for a German MP, and in 2014, joined VCI, Frankfurt, Germany, as personal assistant to the Director-General. Since 2018, she has been based in Berlin, Germany, and responsible for energy policy at the VCI.

Manfred Ritz is VCI’s Head of Media and Editorial and has been with the VCI, Frankfurt, Germany, since 1987.