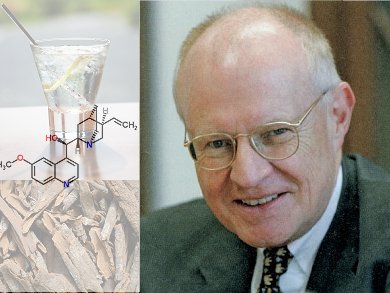

Cinchona, or quina, refers to a genus of about 38 species in the family Rubiaceae, first found in forests of the tropical Andes. Known to natives in Peru as “quinaquina” (bark of the barks), it is perhaps the greatest gift from the New World to the Old World. In particular, its bark yielded the first effective remedy for malaria, one of the most dangerous of infectious diseases. The chief component of cinchona bark, quinine, is still used as a medication, but also for preparing tonic water and Bitter Lemon. There is thus good reason for having a closer look from a chemical point of view at this bitter tree bark.

The Braunschweig quinine producer Buchler & Co., Germany, was established in 1858 by Herman Buchler. Today the Buchler family retains 60 % of the corporate shares, with the balance distributed among 32 personal shareholders. ChemViews magazine authors Klaus Roth and Sabine Streller spoke with Thomas W. Buchler, chief executive officer of the firm and great-grandson of the founder.

Mr Buchler, could you outline for us the role played by Buchler GmbH in the world quinine market?

Today there are still seven producers of quinine worldwide: six in India, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, together with Buchler GmbH in Braunschweig, Germany. We extract daily 15 t of cinchona, and with 80 employees operating in two shifts, we generate annual sales of around EUR 15 million. Our world market share of 25–30 % makes us the world’s leading producer, and the only such operation in Europe.

We export 95 % of our output, quinine being the chief product. Of that, 70–75 % is destined for the pharmaceutical industry, largely for treatment of malaria; 20 % goes to producers of such beverages as tonic water and Bitter Lemon, with the remaining 5–10 % for the chemical industry.

Let us sketch the general pathway leading from raw material to the final products. Where, for example, do you obtain your cinchona bark?

At present, cinchona is grown commercially in Guatemala, India, Indonesia, and central Africa. We obtain our bark primarily from the eastern edge of the Democratic Republic of the Congo; the country was once known as Zaire.

Is it not problematic to rely on raw material shipments from such an unstable region?

Of course, but after nearly 50 years of working in this field I have come simply to accept the fact that cinchona grows only in places that are exceedingly unstable, either geologically or politically. The situation in DR-Congo is particularly depressing, however, because that country is one of the richest on earth from the standpoint of mineral resources, while it ranks at the same time as the second most impoverished land with respect to per capita income.

The best preconditions for a profitable cinchona plantation are found in the eastern provinces of North and South Kivu. Unfortunately, since gaining its political independence, the DR-Congo has never enjoyed peaceful circumstances; since 1994 the scene of the bloodiest conflicts has been the border regions between the DR-Congo and its neighbors Ruanda, Burundi, and Uganda.

How should one visualize the process of buying bark in the Eastern DR-Congo?

The chief cinchona marketplace in North Kivu is in the city of Butembo. We buy our bark through intermediaries there, most of whom we have worked with for years. The bark is then transported to one of the nearest ports: Mombasa in Kenya or Dar-es Salam in Tanzania. Depending on the route and season, this takes 2–6 weeks, in the course of which we generally have to put up with a host of shenanigans, supposedly due to “government authorities”. Subsequent ocean transport consumes another 4–6 weeks before our cargo finally arrives in Hamburg, Germany. That part of the journey is generally relatively harmless, but on one occasion a ship carrying a substantial load of cinchona bark collided in the harbor of Bombay (Mumbai) with another ship, and then sank. The result was a very large batch of true Indian Tonic Water …

When you buy bark in Eastern DR-Congo, how do you determine its quality, and ultimately the price?

To begin with, at the time of sale we give the dealer only a down payment. When the goods arrive here in Braunschweig we immediately withdraw a batch of samples: in the case of shipments from plantations with which we are familiar, samples are taken from every third sack; otherwise we test every sack. A neutral laboratory then establishes the quinine content of the samples, after which we pay the dealer the rest of what we owe, the final price being dependent upon the quinine level. In essence, we reimburse on the basis of the amount of quinine we are purchasing, not the quantity of crude bark. This obviously encourages our intermediaries to pay attention to quality, and it strongly discourages, for example, any mixing in of worthless eucalyptus bark, which looks very similar to cinchona bark. It is the development, over the course of many years, of a strong sense of confidence in terms of the dealers with whom we work that makes this sort of transaction possible—one that is fair to both parties.

You can, of course, imagine that, given the insecure political situation, we always need to maintain here on site an adequate reserve of bark: in the order of a year’s supply.

How do you then process the bark?

In our extraction plant the bark is first finely ground, after which it is digested with quicklime and dilute sodium hydroxide solution. The swollen bark powder obtained in this way is then extracted for several hours with toluene. The resulting organic phase contains all the cinchona alkaloids, as well as fats and resins that are extracted simultaneously. The mixture is then filtered.

The filter residue, still moist with toluene, is next treated with steam as a way of driving off and recovering the toluene. The final bark residue, which is permitted to contain at most 2 ppm of leftover toluene (i.e., 2 g of toluene per ton of bark material), is combusted in an appropriate way as a heat source.

The toluene phase from above is treated with dilute sulfuric acid in a set of liquid/liquid extractors. Since the cinchona alkaloids are amines, and thus basic, they are converted by the sulfuric acid into salts, causing them to pass into the aqueous phase, whereas fats and resins remain in the toluene. The organic phase is separated, toluene is recovered by distillation, and the remaining dark brown, oily resins and fats are disposed of—again in a proper way, ultimately with incineration.

The aqueous phase, which contains all of the cinchona alkaloids, is worked up further in the chemical plant. Following precise modification of the pH, approximately 70 % of the quinine present crystallizes out in this very first step. In the end we manage to isolate ca. 30–40 kg of quinine from every ton of bark.

As suggested, the mother liquor contains additional quinine, together with other cinchona alkaloids, which are isolated and purified via a number of further crystallization steps. In addition to quinine, quinidine, cinchonine, and cinchonidine we also isolate quinic acid, as well as various synthetic products derived from the cinchona alkaloids. For more information, see www.quinine-buchler.com/index.htm.

Crystallizates that are intended to constitute end products from the chemical division are subjected to careful analytical tests for purity and residual solvent content; they are accepted for further processing in the pharmaceutical division only when they conform to established fixed criteria for purity.

You appear to make a sharp distinction between your chemical and pharmaceutical operations. What is the significance of that?

The two divisions are indeed entirely separate, and are in fact housed in separate buildings. In the pharmaceutical division we work exclusively with water as a solvent, so that it is no longer necessary for those rooms to be protected against explosions.

Above all, however, this complete separation became necessary in the 1970s, when stricter requirements were introduced regarding pharmaceutical production centers, insisted upon especially by the United States. Because the USA represented our most important market for quinine and quinidine, it was essential that we adapt our operations accordingly. Still today we are audited on a regular basis by, among others, the FDA (Food and Drug Administration).

What does all this mean in practice?

In our pharmaceutical division we operate strictly according to the standards of GMP (Good Manufacturing Practices), which is to say by specific standardized rules with respect to cleanliness, hygiene, evaluation, analytics, production supervision, employee training, and above all documentation. Consider this single example: We ourselves continuously monitor the quality of our water, even though its purity is already overseen by the municipal waterworks.

Especially for a middle-sized business, production consistent with GMP and the associated audit systems represents a huge investment. We devote more than 15 % of our full-time equivalent workforce to safety, quality control, and quality assurance with respect to our operations. That sort of thing can often be truly painful for a businessman like me. But look: Recently we celebrated the 150th anniversary of the firm, and we ourselves often ask how we have been able to survive for so long.

So, what do you think are the reasons?

One reason is probably the limited market, which makes this business of little interest for a large firm. Acquisition of raw materials from unstable parts of the world is extremely difficult, and it presupposes personal relationships of trust with our partners on site, relationships developed over the course of many years. We know each other, and we know we will be in touch again at the next harvest. The quinine business is never a speculative one, but is always arranged with a view toward the long term. The quarterly income statements that are regarded as so crucial in a large firm would be useless here. As a medium-sized company, that works to our advantage.

Finally, we also have the advantage of our location. The expensive extraction facilities that are required are in our case not in some politically and/or geologically unstable region, but right here in Braunschweig. For that reason, ours has so far been the only quinine factory in the world able to fulfill all the requirements laid down by the pharmaceutical and food industries with respect to modern production technology and supervision, allowing us to offer a guarantee of quality. We demonstrate this quality through continual validation, which in turn gives us an edge in international competition. We intend to do all we can to see to it that this remains the case.

Mr Buchler, we are grateful to you for this conversation.

Prof. Klaus Roth

Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

Dr. Sabine Streller

Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

The article has been published in German in:

and was translated by W. E. Russey.

From Pharmacy to the Pub — A Bark Conquers the World: Part 1

The quinine-containing bark of the Cinchona tree is probably the most valuable drug the Americas gave the world.

From Pharmacy to the Pub — A Bark Conquers the World: Part 3

The long way from the structure determination to the total synthesis is an exciting detective story.

From Pharmacy to the Pub — A Bark Conquers the World: Part 4

Last but not least, besides explaining how quinine helps against malaria, we talk about drinks containing this wonderful alkaloid, no matter whether stirred or shaken.

See all articles by Klaus Roth published by ChemViews magazine