“There is no country, from the polar regions in the north to New Zealand in the south, where the inhabitants don’t practice tattooing” observed Charles Darwin in his “Origin of the Arts”. The current renaissance of tattooing revisits a tradition fostered in numerous cultural environments over centuries.

What happens under the skin during and after the introduction of the pigments? Here, we pursue tattooing from a chemical perspective.

1. A Historical Glance at Tattoos

1.1 From Ötzi to James Cook

Ötzi was the first person we know of who was tattooed. A total of 61(!) tattoos adorned his body [1] – limited to crosses and parallel bars, but executed very precisely. Soot particles were rubbed into gashes opened into the flesh [2]. Other archeological finds suggest that in other cultures, predating Ötzi, tattooing was also practiced. Over the course of centuries, traditional techniques and artistic developments led to an impressive cultural diversity of pictorial forms of expression on human skin [3,4].

|

|

|

Figure 1. Omai, the Tahitian. (Painting by Joshua Reynolds ca. 1776). (Source: wiki-media commons, Botaurus, public domain). |

In Europe and adjacent Mediterranean regions, the societal acceptance of tattooing experienced a constant rise and fall: between condemnation and esteem. In Leviticus 19, 28 (King James Version) it says explicitly “Ye shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor print any marks upon you: I am the LORD.” In fact, in Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, tattooing is and has been to some extent rejected as an encroachment upon God’s creation. Only God has this right (Genesis 4, 15). Thus, he punished Cain after the latter had slain Abel, condemning him to life as a leper with a mark on his face.

Despite the sanction, tattoos of a cross or a fish on the forehead or the wrist were common among early Christians as professions of faith. Paul wrote in his letter to the Galatians (6, 17): “From henceforth let no man trouble me: for I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” Nevertheless, official church doctrine rejected tattooing as a heathen practice, and in 787 B.C., Pope Hadrian I issued a total ban on it. Still, this did not prevent the Crusaders from having symbols of their faith tattooed onto their flesh, so that they would be provided with a Christian burial in case of their death.

Tattooing first became popular in Europe through descriptions by Captain James Cook (1728–79) of his south-sea travels. He reported: “Both sexes apply ‘tataus’ (as expressed in their language) to their bodies, in that an indelible black figure is superimposed over a white background, both pigments being insoluble. Some have horrible looking representations of male birds and dogs … Briefly put, they display in the application of these illustrations a diversity, both in quantity and location, that seems to depend only on the mood of the individual. Men and women display them with great delight.”

In 1774, Cook brought a young Tahitian, Omai, back to London with him, and presented him in polite society (see Fig. 1). Women, in particular, were delighted, taking the dotted decorations on his hands and arms as script directly from paradise. The expression “tatau”, meaning “appropriate striking” [5], was soon transformed into the English “tattoo” and the German “Tatuieren” and “Tätowieren”. Prior to Omai’s turning up, tattooing as a process was referred to as “pricking” or “poking”.

1.2. 19th Century

In the course of the 19th century, tattooing experienced a real blossoming in central Europe. By the end of this period, more than 20 % of the population had undergone the process [6], however, with a very disparate social distribution. Tattooing enjoyed great popularity in both the aristocracy and the lower classes, in both cases as a distinction from other groups.

Aristocratic families were glad to see their sons prepare to become naval officers, many of whom returned from Asia with a tattoo. King Edward VII of England adorned his body with numerous religious symbols, and his son, later to become King George V, displayed a dragon on his left upper arm (see Fig. 2). Czar Nicholas II, Kaiser Wilhelm II, King Constantine of Greece, King Oscar of Sweden, and the English Prince Consort Albert all bore tattoos. Queen Olga of Greece and Queen Victoria were said to have concealed tattoos.

The beautiful Sisi, Empress Elizabeth of Austria, allowed an anchor to be tattooed on her shoulder at the age of 51 in the course of a trip to Greece. Her husband, Kaiser Franz Joseph I, was appalled, and asked their daughter Marie Valerie if she had “wept,” but the latter found it “very original, and certainly not so terrible” [7]. The negative attitude of his father also did not prevent Crown Prince Rudolf from following his mother’s example and allowing himself to be tattooed.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Examples of prominent persons with tattoos. |

Ordinary civil society regarded the tattooing of aristocrats as a quirky, crazy idea, but tolerated it among sailors as a sign of pride in their profession. Otherwise, they took it as an indication of criminality, prostitution, or insanity. Adolf Loos (1870–1933), one of the trailblazers of modern architecture, even suggested the consigning of aristocrats and criminals to a single category in his paper “Ornament and Crime” from 1908 [9]:

“The modern individual who lets himself be tattooed is either a criminal or a degenerate. There are prisons in which eighty percent of the inmates are tattooed. Those who are tattooed but not imprisoned are either latent criminals or degenerate aristocrats. If one who is tattooed dies free, he will have died a few years before committing a murder.”

1.3. 20th Century

This connection between a tattoo and asocial elements and degenerates was followed by legal prohibitions and societal condemnation, which led to the demise of tattooing in the 20th century, not only in Europe, but also in countries with centuries-old tattooing traditions. Only very recently have indigenous peoples of the South Pacific, Australia, New Zealand, and Asia experienced an increased pride in their own cultural traditions through this nearly forgotten metaphorical language.

Toward the end of the 1960s, tattoos became a popular expression of protest against the bourgeois establishment by the “Hippie Generation” in Europe and North America. Pop-, rock-, and sports stars were the trendsetters. Traditional motifs from other cultural circles were especially favored, but these colorful prototypes (some from the Japanese criminal subculture of the 19th century) lost all their ritual and spiritual significance with Western adaptation, degenerating into interesting, decorative elements.

In the last two decades, artistically-minded tattooists began to breach the boundaries of traditional imagery and raised tattooing to a new art form with nearly boundless design flexibility. Especially talented tattooists have become internationally celebrated “stars”, and their work has accordingly become expensive. A dynamic, flourishing market arose, which as of 2012 in the United States had reached an overall volume of $1.65 billion – and counting.

2. Why do People Undergo Tattooing?

This answer is easy. Tattooing satisfies an age-old urge of mankind. In a certain sense, skin constituted the first canvas upon which people could convey information, provided the symbols would be understood. Thus, a lifelong affiliation with a particular community might be signaled. Coptic Christians in Egypt to this day bear a tattooed cross on the inside of the right arm. Also, individual tribes (e.g., the Maoris) have used tattoos as distinguishing features. On the other hand, tattoos have also acted as exclusionary features: criminals, slaves, and outcasts were made broadly recognizable.

Within a community, tattoos may indicate social rank. At the end of puberty, for instance, a transition to adulthood may be made visible. Among the indigenous peoples of Samoa, one’s manhood was first acknowledged when the young person had been tattooed, and proof had been presented that he could endure pain.

In contemporary Western industrial society, the significance of tattooing has changed radically. A decision to subject oneself to a tattoo generally is not made rationally, but rather emotionally. Countless conscious and subconscious factors tend to be involved, with different weights for each individual. From increasing one’s attractiveness to expressing political leanings – all that and more can contribute to the decision to get a tattoo. Demonstration of one’s uniqueness seems to stand in the foreground. Again, this often applies to people who are in, or have recently passed through puberty, when they acquire a first tattoo as an expression of newly discovered freedom to make decisions regarding their bodies. One no longer wishes to look like his (or her) parents, but rather like personal idols from the worlds of music or sports.

Technical skill, artistic ability, a good set of tools, and high-grade pigments determine the quality of a tattoo, both in terms of visual impact and durability, as well as limited risk of long-term health damage. It is time now, however, for us to pursue step by step the process of actually applying a tattoo, starting with the skin as a painting surface and extending all the way to the healing process.

3. The Skin as a Canvas

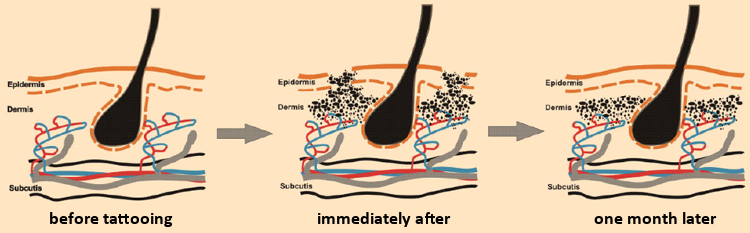

From the outside in, the skin consists of three layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutis (see Fig. 3). In the lower part of the epidermis, new cells (keratinocytes) are constantly being developed, and these gradually wander to the surface where they die, constituting the external callus. Due to this constant cell renewal, foreign bodies in the epidermis are transported to the surface of the skin within a few weeks and then eliminated.

|

|

|

Figure 3. Skin structure and pigment layering. |

The coloring particles for a tattoo should, on the one hand, be embedded deeply in the dermis, since only there will they remain, due to the impenetrable barrier to the epidermis. For contrast-rich, sharp contours and powerful colors, the particles should at the same time lie tightly below the surface. It is the job of the tattooist to achieve the optimal compromise between these opposing requirements.

4. Tools for Tattooing

Ötzi’s tattoos were based on the most primitive of tattooing methods. The skin was cut deeply using a sharp cutting edge, and crushed charcoal was rubbed into the bleeding wound. After the wound had healed, sufficient charcoal still remained present in the dermis.

A major improvement on the process was the introduction of the coloring matter with needles. This technique was practiced already in ancient Rome and made possible the creation of patterns and figures with a considerably greater richness of both form and detail (see Fig. 4).

|

|

|

Figure 4. Various tattooing methods. |

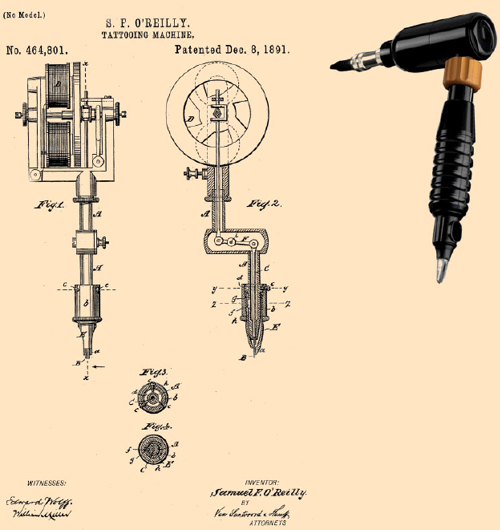

The first electrical tattooing device was patented in 1891 by Samuel O’Reilly, based on an idea proposed by Thomas Alva Edison, and it revolutionized tattooing (see Fig. 5). Over the course of the next 100 years, numerous improvements included developments with respect to functionality and safety. These factors bestowed a great deal of added artistic freedom upon tattooing, especially from the standpoint of design, and provided substantial time savings.

|

|

|

Figure 5. Tattooing devices. |

A tattooist today works with electrical application devices based either on a spooling or a rotational principle. Both methods are employed, but rotational systems are gaining increasing favor due to their simpler handling (lighter weight, more ergonomic). With frequencies between 70 and 170 Hz and a penetration depth of up to 4 mm, needles previously dipped in coloring matter are driven into the skin by the device. Repeated application provides both an even distribution of color and maximum saturation. Complex skin painting in numerous styles is thereby facilitated. The pain factor is not reduced, however. To the contrary: because of the higher rate of pricking, the pain actually increases relati ve to the traditional Thai method of manual tattooing.

ve to the traditional Thai method of manual tattooing.

In Part 2, we continue with more information on the coloring materials employed in tattooing.

Get to know more about tattoos: Interview with a Tattoo Expert

References

[1] M. Samadelli et al., Complete mapping of the tattoos on the 5300-year-old Tyrolean Iceman, J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 753–758. DOI: 10.1016/j.culher. 2014.12.005

[2] M. A. Pabst et al., The tattoos of the Tyrolean Iceman: a light microscopical, ultrastructural and element analytical study, J. Arch. Sci. 2009, 36, 2335–2341. DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2009.06.016

[3] J. Höck, M. Kastning, Der Körper als Leinwand (in German), SWR2 radio broadcast, 11 March 2011. (PDF)

[4] N. Thomas, A. Cole, B. Douglas (Eds.), Tattoo, Reaction Books, Ltd., London, UK, 2005. ISBN: 978-0-8223-3550-4

[5] P. Mesenhöller in [4].

[6] W. Regal, M. Nanut, Unauslöschlicher Schmuck (in German), Ärzte Woche 2009, 271.

[7] M. Haller, Vom Kainsmahl zur Körperkunst (in German), SWR2 Essay, 2013. (PDF)

[8] L. Fischer, Schattenwürfe in die Zukunft, Kaiserin Elisabeth und die Frauen ihrer Zeit (in German), Böhlau Verlag, Wien, Österreich, 1998. ISBN: 978-3-205-98765-9

[9] A. Loos, Ornament und Verbrechen (1908) in Adolf Loos: Sämtliche Schriften in zwei Bänden (in German), Vol. 1, Herold Verlag, Vienna, Austria, 1962, 276.

[10] Patent US 464801 A.

[11] MT.Derm GmbH, Berlin, Germany, Cheyenne Professional Tattoo Equipment, 2016.

The article has been published in German as:

- To Tattoo or not to Tattoo,

Henrik Petersen, Klaus Roth,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2016, 50, 44–66.

DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.201500740

and was translated by W. E. Russey.

To Tattoo or Not to Tattoo? – Part 1

Tattooing from a chemical point of view

To Tattoo or Not to Tattoo? – Part 2

Coloring materials employed in tattooing

To Tattoo or Not to Tattoo? – Part 3

The process of tattooing

To Tattoo or Not to Tattoo? – Part 4

Tattoo removal, permanent make-up, and henna

See all articles by Klaus Roth published in ChemistryViews Magazine