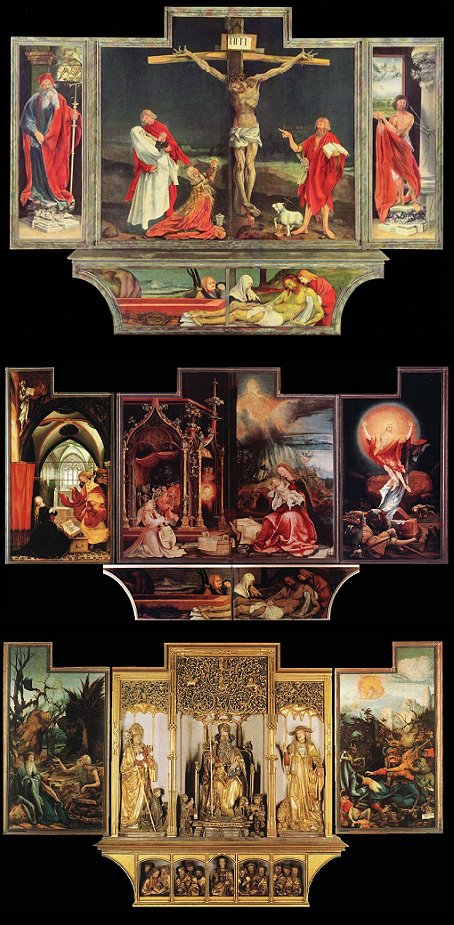

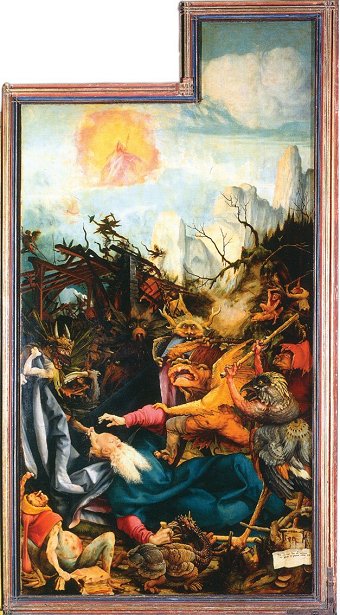

The Isenheim altar is counted among the most beautiful altarpieces in all of Western art (see Fig. 1). Especially famous is the imaginative representation of the “Temptation of Saint Anthony”. Matthias Grünewald unsettles the observer with a band of horrible demons besetting and abusing the frantic Saint from every direction.

Figure 1. The Isenheim altar. Top: The closed polyptych shows the crucifixion in the center, and below it the entombment; left, Saint Anthony, and right, St. Sebastian. Center: At Christmas, Easter, and Our Lady days, the center position shows views of the Annunciation, the Choir of Angels, Christ’s Birth, and the Resurrection (symbols of joy and hope). Bottom: on St. Anthony’s Day the altar is fully opened, providing the faithful with a view of the carved figures by Nikolaus Hagenauer. St. Anthony is enthroned between St. Augustine and St. Jerome. Two pigs at the feet of St. Anthony are intended to remind the faithful discretely to donate to the Order. The carvings are flanked on both sides by Grünewald’s portrayals of St. Anthony’s encounter with St. Paul in the wilderness (left), and the temptation of St. Anthony (right). © Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar, France.

Most especially moving is a cripple covered with boils and apparently beset with unspeakable pain. These are consequences of “St. Anthony’s Fire”, a condition that occurred in epidemic proportions, and led to the deaths of countless victims. It was a matter of centuries before “St. Anthony’s Fire” was finally recognized as the result of poisoning through the ergot fungus, thriving on the rye that served widely as a basis for bread.

Here we examine the disastrous influence that alkaloids from ergot have had in human history.

Symptoms of St. Anthony’s Fire

Alongside frequent major disease outbreaks like plague and cholera, ancient sources offer moving reports of yet another type of horrible epidemic that raged again and again, most recently in the 18th century: ergotism, known by various colloquial names depending in part on the most prominent initial symptoms.

One form of ergotism typically manifests itself first through pains in the extremities, which in the course of a few days or perhaps weeks are followed first by dark red and later black discolorations. Entire parts of the body then become subject to necrosis, accompanied by intense, burning pain. Finally, the pain decreases, and the affected portion of the body instead becomes numb, dies off, shrivels up, and simply falls away: painlessly, and without any bleeding [1]. Victims sometimes were shocked to discover, upon removing a glove or a boot, that it contained a detached finger or toe. There is one report of a woman riding a donkey to a hospital for amputation of a leg, but upon arrival determining that amputation had already occurred: a result of the normal shaking that she experienced in the course of her journey—again, without any pain or bleeding.

An alternative common manifestation of the illness begins with a tingling sensation of the skin. Further development produces extremely painful cramping in the extremities, which may continue for hours. This in turn often proceeds to epilepsy-like attacks, culminating in bodily collapse and unconsciousness. Between attacks the victim is subjected to a voracious hunger. Mortality during the advanced stages is very high.

Brotherhood of St. Anthony

We are fortunate to live in better times, this horrible illness now being virtually forgotten. But medieval doctors found themselves utterly helpless in the face of the situation they were confronted with; given the scope of the calamity it was typically cited in the same breath with the plague and other comparable epidemics, like cholera. From the end of the 11th century, ergot victims were very often cared for in special infirmaries established by charitable monastic orders and lay brotherhoods. One such infirmary was founded in 1090 by the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony in (conveniently!) the village of St. Antoine, near Grenoble, France. It acquired an especially proud reputation in this regard, and is often considered to be the very first of the world’s specialized hospitals. Through its successes, the name St. Anthony became inextricably linked with the condition itself, known today exclusively as the “ignis sacer” (holy fire), or “St. Anthony’s fire”.

The intense, burning pains due to St. Anthony’s fire were symbolized in early pictorial representations by hands and feet shown literally to be burning. St. Anthony himself is usually depicted with a pig lying at his feet, an animal that became a sort of trademark of the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony. Thus, they came up with the clever idea of ensuring their ability to provide patients with high quality sustenance by encouraging persons of limited means to donate to the Brotherhood a piglet, and to hang a little bell around its neck or on its ear as a symbol of its belonging to the St. Anthony Brothers. These pigs were allowed to roam freely, being amply fed with food scraps from people of the village. On the feast day of St. Anthony, January 17, the pigs were slaughtered, and either the proceeds from their sale or perhaps representative choice smoked hams would be donated to the Brothers as a sort of offering.

When sick people sought admission to a St. Anthony Brothers clinic they would first be examined by a doctor to make sure their condition was indeed a case of St. Anthony’s fire, since it was steadfastly believed that the Saint’s intervention would otherwise be ineffective. Admission assured the patient of right to life-long care, although upon the victim’s death, all of his possessions were to be left to the Brothers. Newly admitted patients swore to live a pious and chaste life, to be obedient, and to safeguard the possessions of the Order—which were understood to include one’s own possessions. In this way, the Brothers of St. Anthony grew increasingly prosperous, built more and more monasteries, and could afford to adorn their chapels with valuable works of art, like the Isenheim altar. At their peak, the St. Anthony Brothers were among the very richest of the religious orders, with over 350 monasteries and associated clinics spread throughout Europe, one of them situated in the Alsatian village of Isenheim.

The fact that they specialized in a specific affliction contributed to the success of the Brotherhood, but it also sealed its fate. Once the cause of the condition was brought to light in the 18th century, and epidemics no longer occurred, the Order lost its singular purpose, and in 1776 it was absorbed into the Order of Malta.

In order to become more closely and precisely acquainted with the curative successes of the Brotherhood of St. Anthony, it will be worthwhile to examine in detail an important piece of artwork they commissioned, one in which their specific efforts and religious roots are depicted: the Isenheim altar, a creation of the widely acclaimed master Matthias Grünewald.

The Isenheim Altar

The preceptor of the St. Anthony Brothers monastery in Isenheim, Guido Guersi, in 1511 commissioned a new altarpiece (a retable) in the form of a polyptych, that is consisting of more than three panels, typically hinged, which could be opened at will in one of three ways so as to be appropriate to various parts of the liturgical year. Today the Isenheim altar is available to be admired at the museum Musée d’Unterlinden in the French city of Colmar. In what follows, we focus on the two scenes revealed when the altarpiece is first opened.

“The Temptation of St. Anthony” (see Fig. 2) is certainly the most moving image of the entire altarpiece. The saint is shown being assaulted by a host of monsters and demons: trampled, bitten, and scratched. But he withstands all the torment, and even scoffs at the devilish monsters. Grünewald has attempted to capture precisely that moment in which God finally appears on the horizon and disperses the host of evil spirits. St. Anthony complains bitterly to God: “Where wast Thou, dear Jesus, where wast Thou? Why didst Thou not appear to heal my wounds?“

Figure 2. The temptation of St. Anthony. © Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar, France.

Grünewald captures this reproachful query in cartoon-like form at the lower right edge of the image: “Ubi eras, Jesus bone. Ubi eras quare non affuisti ut savares vulnera mea?” In fact, God has not abandoned him, responding instead: “Anthony, I was here, but I waited so that I could observe your contest. Since you have in fact persisted, and not succumbed, I will always come to your aid, and I will make you famous everywhere” [2].

The cripple shown with fins in the lower left portion of the picture is highlighted through the use of bright colors. Covered with abscesses and with a bloated stomach, his crippled left hand makes it clear that as a consequence of St. Anthony’s he has become a horribly maimed and suffering soul. The moving and at the same time alarming and shocking imagery is meant to exhort the faithful and all sufferers with the knowledge that—just as once with St. Anthony—faith alone is capable of delivering them from their afflictions.

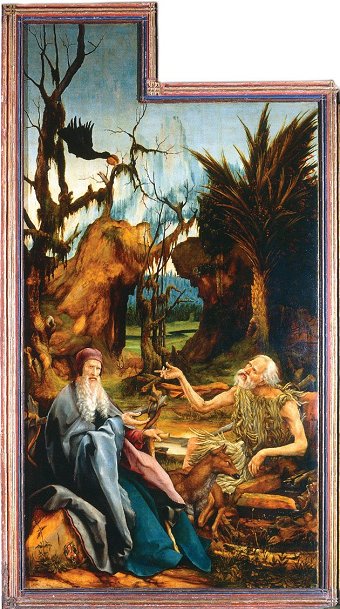

In sharp contrast to this terrifying depiction of the “Temptation of St. Anthony” is the other side of the display at the same time within the altarpiece: “St. Anthony’s Visit with St. Paul in the Wilderness” (see Fig. 3). There radiates from the wilderness conversation between the two hermits a sense of true peace and serenity. St. Paul’s focused attention on the approaching raven leads one to suspect that he is just announcing to the astonished Anthony that in this way God furnishes him daily with a loaf of bread. But on this particular day the raven is bringing two loaves: one for Anthony as well.

Figure 3. St. Anthony’s visit to St. Paul in the wilderness. © Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar, France.

This symbolic bond between God’s gift of bread and St. Anthony induces the Brothers of St. Anthony to impute to bread a special, religious significance in their care of the sick. And indeed, from today’s perspective it becomes possible to ascribe at least some of the curative success of the St. Anthony Brothers to sound nutrition, and especially to the high quality of their bread. Grünewald also tells us more about their symptomatic treatment of skin diseases, but for this we must examine the picture with greater care.

To the casual viewer, the plants growing at the feet of Saints Anthony and Paul represent nothing more than decorative embellishment, but a closer look provides further insight. In contrast to another masterwork, Albrecht Dürer’s famous “Great Piece of Turf” (“Das große Rasenstück”), what is shown here is no random snippet out of the Alsatian flora: the very detailed representation includes plants from a variety of biotopes, including swamp, meadow, forest, and dry ground. The herbs depicted symbolize, with their healing capacities, the power of faith to overcome even seemingly hopeless situations, just as St. Anthony himself demonstrated. Therefore, the Brothers administered as therapy to their patients a “St. Anthony’s wine”, based on herbs, and for alleviating the skin afflictions, a “St. Anthony’s balm” that they themselves prepared. In 1952 there was published a botanical determination of all 14 plants [3] depicted on the Isenheim altarpiece, but critics have more recently cast doubt on the accuracy of the list [4]. The only plants identified with certainty are the three growing on the rocks where St. Anthony is seated: plantain (lamb’s foot), buckhorn (ribwort), and verbena, all commonly employed at the time as medicinal herbs (see Fig. 4, Tab. 1).

Figure 4. Herbs in the altar picture depicting St. Anthony’s visit to St. Paul in the wilderness. © Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar, France.

Table 1. Herbs identified in the altar representation of St. Anthony’s visit to St. Paul in the wilderness.

It seems unlikely that Grünewald was intent here on revealing visually the carefully guarded secret of the Isenheim version of St. Anthony’s balm, because in 1992 an authentic formulation from 1726 was accidentally discovered, in which only buckhorn and plantain were present. A reliable interpretation is of course difficult today; perhaps the three herbs at St. Anthony’s feet are only representative of the curative powers of the St. Anthony’s balm, and those at the feet of St. Paul correspond to a “still life” of other, more common medicinal herbs. At least according to the surviving authentic recipe, the Isenheim St. Anthony’s balm was a skin ointment based on fat and tree gum, and containing various anti-inflammatory and analgesic herbs as well as the disinfectant verdigris (alkaline copper acetate) [5].

The Cause of St. Anthony’s Fire

First hints that eating bad bread might somehow be connected with St. Anthony’s fire (referred to by some as “prickling disease”) were provided by the Frenchman Robert Dumont, who surmised in conjunction with the epidemic of 1125 that “the grain had mixed into it dark, corrupted kernels, as a consequence of which the flour became ‘sanguinolent’ (tinged with blood), off-colored, and poisonous” [1]. These dark kernels—ergot, associated with ears of cereals and other grasses—were actually known to the Greeks, the Romans, and even the Chinese. Outbreaks of ergotism must also have occurred in antiquity [6, 7], even though no causal association between the two was recognized. Dumont’s suspicion also failed to win acceptance. Almost 500 years later (!), in 1596, the medical school at the University of Marburg, Germany, issued a report regarding ergotism, in which tainted bread was cited as the cause. The precise nature or origin of the “taint” itself remained open, however.

Eventually the personal physician of the Count of Sully, Tuillier, in 1630 conducted systematic feeding experiments involving ergot and animals, and came to the conclusion that excessive consumption of grain containing ergot was the source of the epidemics in both animals and humans [6]. The modern term ergotism covers both of the recognized forms of the consequences of consuming ergot (Ergotismus gangraenosus and Ergotismus convulsivus), and points directly to their common cause.

Again, Tuillier’s ideas were not universally accepted. For example, in Germany in the 17th century, ergotism was widely regarded as a form of scurvy [7]. Discussion among scholars as to the role of ergot persisted until the end of the 18th century. Finally, around 1770, the court physician of the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, Theodor August Schleger, suggested a series of animal studies in order to determine, for ergot, the possible effects of storage time and administration form [8]. Most of Schleger’s experiments with dogs, cats, houseflies, a badger, chickens, a pig, a sheep, and carp showed almost no effects whatsoever. Moreover, regardless of the form in which ergot was administered, whether blended with water, baked into bread, or inhaled, it acted as “neither a purgative nor an emetic”—causing instead at most an increased appetite. Only the sheep suffered after an injection of an aqueous infusion of ergot in water: through convulsions in the limbs, difficulty breathing, and an inability either to eat or to drink. The next day the animal declined into rigidity. After being put to death, it was examined by a “very experienced, expert veterinary man”. Its body was opened, and in the breast and abdominal cavities, as well as in the heart, were found both water and blood, “which had congealed into rather solid polyps”. As horrible as these animal tests may seem today, only in this way could the toxicity of ergot be firmly established.

Thus, at the end of the 18th century, the ergot content of grain, especially rye, was clearly recognized as the actual cause of ergotism. Appropriate edicts and bans concerning the use for baking purposes of grains contaminated by ergot were issued in many parts of Central Europe. Nevertheless, the source and especially the biological nature of ergot remained utterly obscure.

References

[1] R. Kobert, Hist. Stud. Pharmakol. Inst. Kaiserl. Univ. Dorpat, 1889, 1.

[2] Chap. 10 in Atanasius vita antonii: www.unifr.ch/bkv/kapitel44.htm

[3] W. Kühn, Ann. Soc. Hist. Litt. Colmar 1951/52, 20.

[4] http://joerg-sieger.de/isenheim/menue/frame10.htm; The web pages of Pastor Jörg Sieger (http://joerg-sieger.de/isenheim.htm) are an excellent source for a deeper understanding of the Isenheim altar.

[5] E. Clémentz, Antoniter-Forum 1994, 2, 13. (detailed formulation)

[6] P. Thieme, Veröff. Geb. Medizinalverw. Richard Scholz Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 1930, 1.

[7] H. Guggisberg, Mutterkorn, Karger, Basel, Switzerland, 1954, 52.

[8] D. T. A. Schleger, Versuche mit dem Mutterkorn, Hofbuchdruck Henrich Schmiede, Kassel, Germany, 1770.

Prof. Klaus Roth

Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

Dr. Sabine Streller

Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

The article has been published in German in:

and was translated by W. E. Russey.

A Chemical Examination of the Isenheim Altar: Role Played in History by Horned Rye Part 2

Looks at what it means when a kernel of grain is infected with ergot, the life-cycle of the fungus, and how it may have contributed to the Salem witch trials

A Chemical Examination of the Isenheim Altar: Role Played in History by Horned Rye Part 3

Looks at the isolation and structural determination of the potent ergot alkaloids, chemical knowledge that guarantees we can enjoy our daily bread without harm

Other articles by Klaus Roth published by ChemViews magazine:

- In Espresso — A Three-Step Preparation

Klaus Roth proves that no culinary masterpiece can be achieved without a basic knowledge of chemistry

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000003 - In Chocolate — The Noblest Polymorphism

Klaus Roth proves only chemistry is able to produce such a celestial pleasure

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000021 - In Sparkling Wine, Champagne & Co

Klaus Roth shows that only chemistry can be this tingling

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000047 - In Chemistry of a Hangover — Alcohol and its Consequences

Klaus Roth asks how can a tiny molecule like ethanol be at the root of so much human misery?

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000074 - In The Chemist’s Fear of the Fugu

Klaus Roth shows that the chemist’s fear of the fugu or pufferfish extends as far as the distinctive and intriguing poison it carries

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000104 - In Chemistry of a Christmas Candle

Klaus Roth explains that when we light a candle, the chemistry we are pursuing is not only especially beautiful, but also especially complex

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000133 - In Pesto — Mediterranean Biochemistry

Klaus Roth uncovers the nature of this culinary-chemical marvel, and thereby comes to enjoy it all the more

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201200001 - In Boiled Eggs: Soft and Hard

Klaus Roth examines an egg on its journey from hen to table to ensure the perfect breakfast egg

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201200018 - Chemical Secrets of the Violin Virtuosi

What made Stradivari’s violins so special? Klaus Roth looks at the important role of chemistry in Stradivari’s workshop and instruments

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201200076 - Chemical Production in Compliance with Torah and the Koran

The unusual interface between chemistry and religion, drawing upon examples from Islamic and Judaic law

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201200088 - Video Interview with Klaus Roth

See all articles published by Klaus Roth in ChemViews Magazine