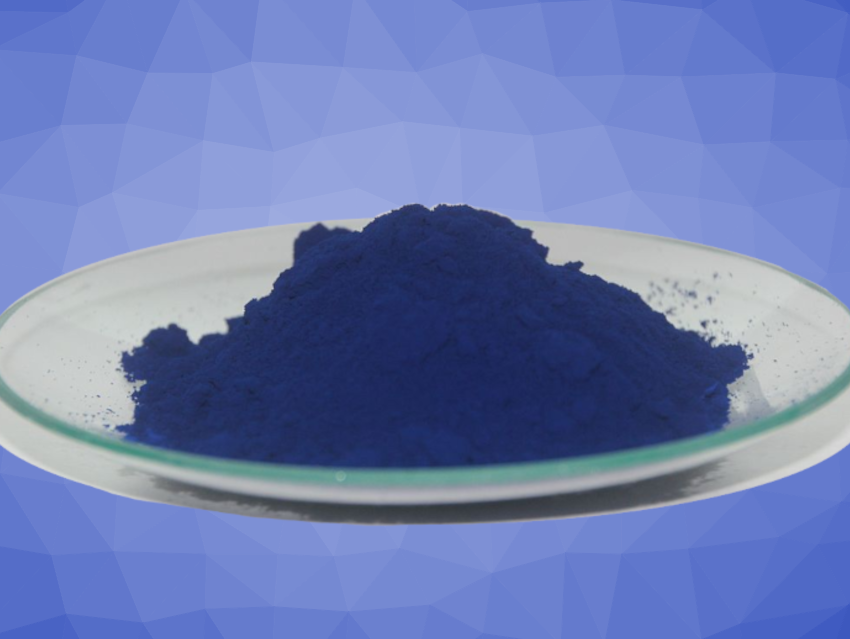

From the beginning, many legends and stories have swirled around the 1706 discovery of Prussian blue. The highly lucrative and initially secret process was revealed in 1724, causing the Berlin alchemists to lose their monopoly. Within a short time, Prussian blue factories were erected in many countries. In light of the huge economic damage this caused Berlin entrepreneurs, one question arises: Who gave away the recipe? This exciting mystery was only solved in 2008.

6 Who Gave Away the Recipe?

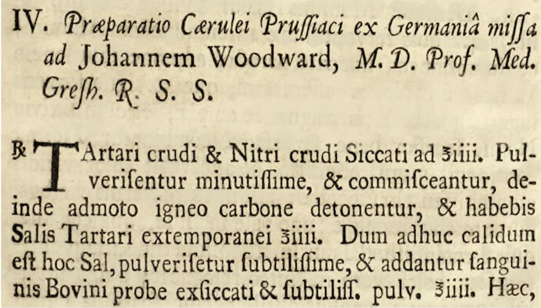

Even the title of the original publication in 1724 [18] smelled of international industrial espionage (see Fig. 9).

|

|

Figure 9. Betrayed by an anonymous manuscript [18]. |

6.1 The Anonymous Manuscript

“Præparatio Cœrulei Prussiaci ex Germania missa ad Johannem Woodward” – “Recipe for the preparation of Prussian Blue from Germany sent to John Woodward”

According to this, John Woodward, a surgeon, geologist, and prominent member of the Royal Society, was not the author but the recipient of a manuscript sent to him personally and in confidence from Germany. The name of the sender was not given. This was not just an extremely unusual publication process, but one that remains unique in the realm of the natural sciences to this day. Normally at that time, like today, no editor of a scientific publication would accept a manuscript without naming the author.

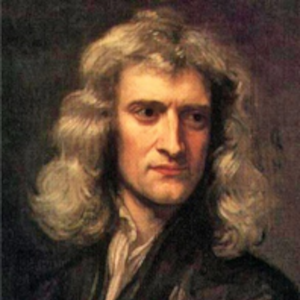

What drove John Woodward to do this? What prompted the Royal Society, under their then President, Isaac Newton, to allow this? Especially because it was clear that Woodward didn’t just know the sender, but that there must have been a relationship of great trust between the two men.

|

|

Isaac Newton (1646 – 1726/27); |

6.2 The Reviewer

One clue was provided by the immediately subsequent publication of chemist John Brown’s, “Observations and Experiments upon the foregoing Preparation” [19] (see Fig. 10):

|

|

Figure 10. The betrayal – the reviewer [19]. |

“Dr. Woodward recently submitted a communication to the society (which he received from someone else), in which the production of Prussian blue was described. I am ready to verify this in detail…”

Peer review of a submitted manuscript by a technically qualified member of the Royal Society was normal and necessary to ensure scientific quality. In this case, however, it was primarily to justify the unusual publication of an anonymous manuscript.

John Brown (also Browne) reviewed the production procedure in detail and coined the term “blood leachate” for the leached product described as “Solution 1” in the process (see Fig. 8). Overall, Brown confirmed the correctness of the manuscript, and thus, the scientific competence of the anonymous author. This was enough for the Royal Society to publish the manuscript without naming an author.

6.3 The Author Is Named Almost 300 Years Later

John Woodward and the Royal Society remained silent about the identity of the German sender. Only in 2008, almost 300 years later, did German chemistry historian Alexander Kraft come across the transcripts of a “classified” letter exchange between John Woodward and Caspar Neumann in the archives of the Royal Society. In 1723, Neumann asked Woodward if the Royal Society would be interested in the recipe for Prussian blue and whether they would publish it in the Philosophical Transactions without naming an author. He wrote:

“I am still deeply indebted to the Royal Society and have reflected for a long time about how I could reduce this debt. I could not find anything in this direction until I came across a certain blue pigment with a color as bold as gentian. It is precipitated from alum and sal alkali (author’s note: potash) with a few tricks and technical steps. Painters can make outstanding use of it as a substitute for ultramarine. Its inventor lives in Berlin. His name is Mr. Frisch, a deputy headmaster of a school in this city, and he is the only person who can produce it. He sells it in large quantities in Germany and Italy, possibly also in England, though I am not certain.”

“Provided it is of interest, I am prepared to reveal the secret for the Royal Society. If this is not the case, I would not disclose it, so that the gentleman is not deprived of his profit, as he is a good friend of mine. In fact, we have not exchanged one word or letter about it but rather I have worked out the production method through many experiments using my own efforts and at great cost. I am now able to produce this pigment in light, dark, violet, or purple colors. However, I do not wish to publish it under my own name. Instead, I would agree if someone else would be prepared to appear as the author.”

In his reply, Woodward must have signaled an interest in this industrial secret and the willingness of the Royal Society to publish the recipe without the name of the author, because on November 17, 1723, Caspar Neumann sent the manuscript, written in Latin, to Woodward [20].

7 Caspar Neumann (1683 – 1737)

Who was this D(octor). C. Neumann, who betrayed the profitable secret “of his good friend” Johann Leonhard Frisch?

Caspar Neumann was born in 1683 in Züllichau in the Brandenburg region. He completed studies in pharmacy and came to Berlin in 1705 to work at the “Black Eagle” pharmacy. Soon thereafter, he became the traveling pharmacist to Frederick I, a position he held until 1711. He accompanied the king on his voyages and impressed him with his professional knowledge and his sublime performance on the harpsichord. In 1711, Frederick I rewarded him for his services with an educational tour of Europe to broaden his chemical and pharmaceutical knowledge.

After many stops, news of Frederick I’s death reached Neumann in London in 1713. The king’s son, Frederick Wilhelm I (1688–1740, the “Soldier King”), promptly dismissed him (“we require him not”) and withdrew all financial support pledged by his father. Neumann was suddenly left without money or a position.

His London colleagues found a generous patron in surgeon Abraham Cyprianus, who allowed Neumann to carry out research in his laboratory undisturbed and without worries. Neumann was invited to the regular meetings of the Royal Society and socialized with Isaac Newton, the President at the time, Sir Hans Sloane, and most of all with John Woodward, with whom he forged a true friendship (see Fig. 11).

|

| Figure 11. Caspar Neumann (1683–1737). Image source: Bundeswehr Medical Academy, Munich, Germany. Painting from around 1736. |

Neumann decided to take up residence in London. He returned to Berlin one more time to settle his personal affairs. There he met with Georg Ernst Stahl, Frederick Wilhelm I’s personal physician. Stahl recognized Neumann’s capabilities and tried to convince him to return to Berlin. He was offered the future position of court pharmacist and the immediate payment for the resumption of his interrupted educational tour. Neumann could not turn this down. He commenced his journey in 1716 with longer stays in Paris and Venice and was appointed court pharmacist in early 1719 [22].

|

|

Georg Ernst Stahl |

As Prussia’s first pharmacist, Neumann fundamentally reformed German pharmacy and education. His talent for organization was impressive. At the time he took over, the court pharmacy dispensed 8,000 medications to the needy and soldiers annually. Within a few years, this number rose to over 20,000. Neumann was correspondingly appreciated for this. Although he never attended a university, he became a member of the Prussian Royal Society of Science in 1721.

Neumann remained grateful to his London colleagues for the hospitality they showed and the help they gave him for the rest of his life. It was to his credit that he wished to express this toward the Royal Society of London through deeds as well as words. As the highest-ranking pharmacist of Prussia, he naturally could not publish the industrial secrets of a domestic producer, so he chose this unusual detour.

Whether Caspar Neumann “betrayed”, “gave away”, “relayed”, or “shared” the industrial secret of Prussian blue is vigorously debated to this day, 300 years later. However, his achievements as a scientist and organizer are unquestionable. He received multiple honors for his work: In 1725 he became a Foreign Member of the Royal Society at the suggestion of Sir Hans Sloane, he joined the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina in 1728, and became the treasurer of the Royal Prussian Society of Science in 1731.

References

[19] J. Brown, Observations and Experiments upon the foregoing Preparation, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1724/25, 33, 17–24.

[20] A. Kraft, On two letters from Caspar Neumann to John Woodward revealing the secret method for preparation of Prussian blue, Bull. Hist. Chem. 2009, 34, 134–140.

[21] G. Bergmann, Verschollen Und Wiedergefunden – Das Ölgemälde Des Berliner Hofapothekers Caspar Neumann (1683–1737), Wehrmed. Monatsschrift, 2010, 10. wehrmed.de (accessed April 15, 2022)

[22] H. Ludwig, Biographisches Denkmal: Caspar Neumann, Arch. Pharm. 1855, 132, 209.

The article has been published in German as:

- Berliner Blau – Entdecker und Verräter,

Klaus Roth,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2021, 56, 34–49.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ciuz.202100033

and was translated by Caroll Pohl-Ferry.

Prussian Blue: Discovery and Betrayal – Part 1

Around 1700, Berlin was a colorful center of innovation – a scene that led to the discovery of the century: Prussian blue

Prussian Blue: Discovery and Betrayal – Part 2

How Johann Konrad Dippel almost ruined the Prussian blue business

Prussian Blue: Discovery and Betrayal – Part 4

How was Prussian blue really discovered—with luck or a stroke of genius?

Prussian Blue: Discovery and Betrayal – Part 5

Solving the case of the discovery of Prussian blue

See similar articles by Klaus Roth published on ChemistryViews.org