Products from the chemical industry improve the quality of human life throughout the world. Consumers have come to assume that starting materials, methods of production, and end products will all meet the highest of standards. But people in certain faith communities expect even more: strict conformance to religious regulations throughout the production process. Here we examine this unusual interface between chemistry and religion, drawing upon examples from Islamic and Judaic law.

1. The Religious Bases for Muslim and Jewish Dietary Laws

In this article we deal with only a few aspects of this subject, ones selected for their relevance to chemical production processes. ChemViews magazine is not the proper venue for authoritative presentation of the religious bases of Islam and Judaism, nor is this author up to such a challenge.

To begin with, Muslims and Jews are explicitly forbidden to eat any pork. This is often perceived as an outdated example of consumer protection and food safety, intended to shield believers in tropical lands from an especially perishable commodity, one that in addition is often contaminated with trichina, source of the dreaded disease trichinosis. This may once upon a time have been a relevant argument, but with modern methods of refrigeration, high standards of hygiene, and a legally prescribed screening of foodstuffs, such safety injunctions would now seem both excessive and anachronistic.

However, this represents a major misunderstanding! Hygiene is not the issue here, but rather the spiritual purity of certain food and drink. Indeed, both Jews and Muslims differentiate every action, as well as specific ingredients of foodstuffs, and their processing, into “clean” and “unclean”, into halal (Arab.: allowed) and haram (Arab.: forbidden), into kosher and terefah, moral and immoral, right and wrong. As far as what in fact is to be regarded as “clean” and what as “unclean”, God is the one who has made that decision, and then proclaimed the guidelines to believers via the Torah, the Koran, and other sacred writings. What follows here is intended to offer a bit of insight into Muslim and Hebraic dietary laws regarding the religious principles underlying them and the resulting chemical consequences for establishments responsible for preparing kosher and halal products.

1.1 Halal and Haram

Schari’a, the sum total of all commandments related to everyday conduct and behavior for Muslims, is derived from the Koran and other holy scriptures [1]. Muslims see conformance with Schari’a as a test set forth by Allah, not a limitation on personal freedom, and they regard themselves as subjected to just principles of a divinely ordained way of life. Fundamentally applicable is the notion that: Everything Allah has created is halal, which is to say clean, or pure. Forbidden are only those things and actions that are expressly designated by Schari’a as haram.

Since many passages in the Koran can be interpreted in various ways, there have developed over the course of centuries two principal currents in Islam—the Sunni and the Shia, each with its own distinctive schools; e.g., among Sunnis, the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam in Turkey and the Balkans, the Shafi’i in Indonesia and Malaysia, the Hanbali in Saudi Arabia, etc. In other words, there is no such thing as the Islam, but rather a host of “offspring” divisions. From the standpoint of dietary restrictions, however, the Koran provides relatively little latitude for alternative interpretations. The most important regulations are as follows [2].

Halal are:

- all non-animal products, apart from those that are poisonous or intoxicating;

- all nonpoisonous marine creatures;

- the horse and hare, as well as chickens, ducks, and similar fowl;

- all grazing animals, which must however be properly slaughtered according to Islamic law;

- all entrails, milk, and milk products derived from halal animals.

The Islamic method of slaughter proceeds as follows: Using a sharp knife, the windpipe, the esophagus, both carotid arteries and jugular veins, as well as the vagal nerves are severed simultaneously, with a single stroke. In the course of the process, the slaughterer utters the phrase: “Bismallah, Allahu Akbar” (In the name of Allah, Allah is Greater);

Haram are (5th Sura, Verse 3):

- meat from any animal not slaughtered according to Islamic law, or which has simply died;

- all blood and blood products;

- pork, and the meat from predatory animals, including dogs;

- alcoholic beverages and other intoxicants.

The agency charged in Germany with certification, Halal Control in Rüsselsheim [4], refuses categorically to provide halal certification for any meat or meat product of German origin. In their judgment, reliable collaboration with the numerous establishments in the German meat industry is at the moment impossible. Due to the complex processing chains—from slaughterhouse to supermarket—an effective and seamless inspection and monitoring of all chains of production is virtually impossible. In view of recent and diverse “rotting meat” scandals, the informed German consumer is unlikely to be surprised by this decision.

1.2 Kosher and Terefah (i.e., Non-kosher)

Jewish dietary restrictions are generally similar to those applicable to Muslims, but the actual set of laws, the kashrut, is substantially more extensive. Foods that are prohibited were proclaimed by God to Moses, and have been transcribed in the five books of Moses in the Old Testament.

Permitted are [10,11]:

- cloven-hoofed ruminants, such as cattle (oxen), sheep, goats, and deer (Leviticus 11, 3–12 and Deuteronomy 14, 4–8);

- marine creatures with scales and (!) fins;

- most sorts of birds (Leviticus 11, 13–19).

Forbidden are:

- pigs, camels, hare, and rabbits;

- mussels, clams, eel, sturgeon, and whales;

- birds of prey, ravens, ostriches, owls, gulls, and storks.

As with the halal restrictions, what is important here is not simply the type of animal, but also how it is slaughtered. Meat can be kosher only if slaughter has been carried out by a Jewish butcher, who has also examined the entrails. After the act of slaughtering, with certain types of animals the sciatic muscle in the hip joint must be removed (Genesis 32, 33), as well as specific fat and fatty membrane layers (Leviticus 3, 16). Then all the meat must be irrigated and further treated either with salt or by cooking to remove all traces of blood. Only then can it be regarded as kosher.

Devout Jews may eat only meat from a kosher butcher, whereas Muslims, according to the Koran, may eat meat from halal animals if slaughtered by a Christian or a Jewish butcher (5th Sura, Verse 5): Today all good things are permitted to you. And you may eat foods from those to whom the scriptures have been given, just as your foods are permitted to them.

A further prohibition from Deuteronomy (14, 21) reaches much more deeply into Jewish cooking practices: You shall not cook a kid (young ram) in its mother’s milk. More generally, milk-based and meat-based ingredients are to be kept strictly separate—with respect to both storage and cooking. They may also not be eaten together. Thus, an au gratin meat casserole with cheese, such as a lasagna al forno, is strictly prohibited.

As a starting point, it is assumed that pots and pans acquire the taste of foods cooked in them. Meat and milk dishes must, therefore, be prepared in separate utensils, presented in different serving dishes, and eaten with separate silverware. This double household management sounds bewildering to non-Jews, but it presents no problems in a Jewish household. Even children know, for example, that the blue dishes are for cheese and the red for meat, the wooden-handled cutlery is for yogurt and that with metal handles for cold cuts. After a meal with a meat course one must wait a few hours before eating dairy products. Foods containing neither meat nor milk, such as fruits and vegetables, are regarded as neutral or parve, and can supplement dishes with either milk or meat.

Things are actually more complicated still. During the seven-day festival of Passover (Pesach) in the spring, Jewish households are not allowed to contain any leavened bread. The entire home is rigorously purged of every last morsel of leavened bread, and during Passover week strictly Orthodox Jews utilize two additional sets of tableware, one for dishes containing milk and another for meat dishes. During Passover, all foods must not only be kosher, but also “kosher for Pesach”, which is to say guaranteed free of flour, bread, and dough residues, and also not prepared with cereals. Observant Jews are permitted to eat only unleavened bread (matzo). This serves as a reminder of the precipitous flight from Egypt, in which no time was available for permitting bread to rise. To ensure bread dough will not ferment, a maximum of 18 minutes is allowed from first mixing of flour and water until fully-baked matzo is removed from the oven, a provision that levies a heavy demand on baking technology [12]! Other (fermented) grain products such as beer, whiskey, and vodka are also prohibited during Passover.

Like Muslims, Jews do not regard the kashrut as limiting their personal freedom, but see “the dietary laws as teaching us to master our passions. They get us in the habit of curbing the expansion of our desires, mitigating our craving for pleasure, and overcoming a tendency to regard eating and drinking as a mission in life” [13]. Sacrificing culinary delights can lead to temptation, however, and a tale told by one of the former presidents of the Central Council of Jews in Germany (Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland), Paul Spiegel, alludes to human weakness in a heartwarming way, while embracing a bit of self-deprecation [11]:

A rabbi enters a non-kosher meat market. He points to a ham in one of the display cases and says: “Give me four slices from that fish, please”. “Sir, that’s a ham!” replies the perplexed butcher, to which the rabbi calmly responds “Excuse me, but I did not ask you for the name of the fish.”

1.3 Chemical Detection of the Presence of Pork

If, in the course of a confusingly long chain of preparation, an allegedly halal or kosher meat product has in fact had forbidden pork-based material added to it, the transgression can actually be subject to chemical detection. During prolonged heating and drastic mechanical stress, it may be that all cellular structure of the meat will be destroyed, and hence rendered incapable of offering clues to the nature of the animal(s) that served as the source, but the genetic substance DNA remains largely unaffected by cooking and/or mincing. This is what one can probe for evidence.

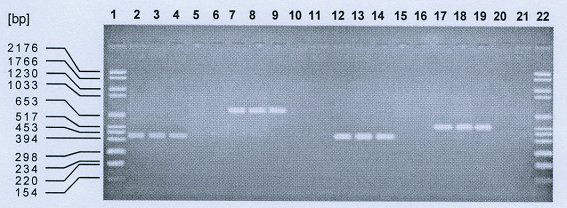

In principle, one selects DNA segments containing a few hundred base pairs, ones that are specific to the animal species in question. With the help of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR technique [5]), base segments from the material under investigation are identified, multiplied, and then separated chromatographically. In Fig. 1 one can see in the left and right lanes (lanes 1 and 22), ladder-like tracks derived from a known DNA mixture.

Figure 1. Chromatogram to determine the prescence of forbidden pork-based additives.

In lanes 2–4 one sees DNA segments specific to a cow (length: 431 base pairs, bp), in lanes 7–9 those specific to a pig (769 bp), lanes 12–15 to a turkey (416 bp), and lanes 17–19 to a chicken (550 bp). In this way it becomes possible to distinguish the various components used in meat products like cold cuts and canned goods. These techniques have now been perfected to such an extent that they are effective even with such highly processed materials as gelatin.

Studies involving random sampling at an independent testing laboratory may reveal major differences between the declared content and the true composition of a variety of meat products. In Germany, for example, unreported turkey was shown to be present in samples from Braunschweiger (liverwurst), through deep-fried chicken, to hot dogs [6–8], and there was evidence also of unreported pork in allegedly “beef” cold cuts [9].

Jewish and Muslim dietary laws have had an impact first and foremost on the food service industry and the closely related food industry in general. This aspect is not the true object of our interest here, however; we propose instead to examine more closely in part 2 the effects on preparation processes involved broadly in the making of halal and kosher products.

References

[1] A. Zaidan, www.halal.de/indexwas.htm

[2] Halal Food Production, M. N. Riaz, M. M. Chaudry (Eds.), CRC Press, Boca Raton, USA, 2004. A review well worth reading.

[4] www.halalcontrol.de

[5] G. Krauss, Chem. Unserer Zeit 1992, 26, 235.

[6] M. Behrens, M. Unthan, Bioforum 1999, 22, 411.

[7] M. Behrens et al., Fleischwirtschaft 1999, 5.

[8] www.cibus-biotech.de

[9] M. Behrens, P. Doderer, www.halal.de

[10] S. H. Dresner, Keeping Kosher, The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, USA, 2000.

[11] P. Spiegel, Was ist koscher?, Ullstein, Berlin, Germany, 2004.

[12] K. Roth, Chem. Unserer Zeit 2007, 41, 400.

[13] www.hagalil.com/judentum/koscher/kaschruth.htm

Prof. Klaus Roth

Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

The article has been published in German in:

and was translated by W. E. Russey.

Chemical Production in Compliance with Torah and the Koran: Part 2

We examine the effects of these restrictions on the preparation processes involved in the making of halal and kosher products

Halal and Kosher Food Production: Interview with Prignitzer Marketing Director and Chief Executive

R.-E. Kühn and W. Krüger, Germany, talk about the challenges of becoming a certified producer of kosher and halal materials

Other articles by Klaus Roth published by ChemViews magazine:

- In Espresso — A Three-Step Preparation

Klaus Roth proves that no culinary masterpiece can be achieved without a basic knowledge of chemistry

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000003 - In Chocolate — The Noblest Polymorphism

Klaus Roth proves only chemistry is able to produce such a celestial pleasure

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000021 - In Sparkling Wine, Champagne & Co

Klaus Roth shows that only chemistry can be this tingling

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000047 - In Chemistry of a Hangover — Alcohol and its Consequences

Klaus Roth asks how can a tiny molecule like ethanol be at the root of so much human misery?

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000074 - In The Chemist’s Fear of the Fugu

Klaus Roth shows that the chemist’s fear of the fugu or pufferfish extends as far as the distinctive and intriguing poison it carries

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000104 - In Chemistry of a Christmas Candle

Klaus Roth explains that when we light a candle, the chemistry we are pursuing is not only especially beautiful, but also especially complex

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201000133 - In Pesto — Mediterranean Biochemistry

Klaus Roth uncovers the nature of this culinary-chemical marvel, and thereby comes to enjoy it all the more

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201200001 - In Boiled Eggs: Soft and Hard

Klaus Roth examine an egg on its journey from hen to table to ensure the perfect breakfast egg

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201200018 - Chemical Secrets of the Violin Virtuosi

What made Stradivari’s violins so special? Klaus Roth looks at the important role of chemistry in Stradivari’s workshop and instruments

DOI: 10.1002/chemv.201200076 - Video Interview with Klaus Roth

See all articles published by Klaus Roth in ChemViews Magazine